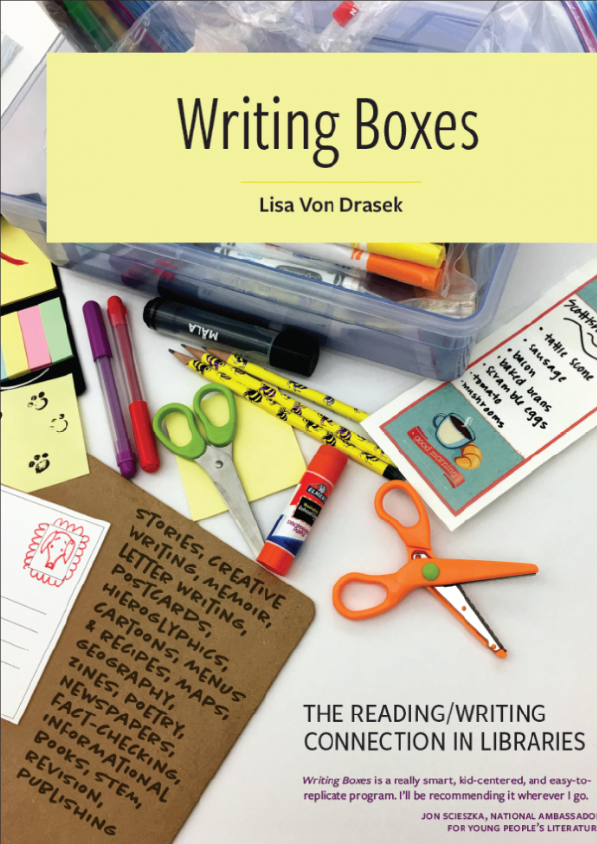

We ask librarians to create “purposeful programs.” Purposeful writing by young writers might include postcards, greeting cards, bookmarks, brochures, menus, ads, personal notes, maps, lists, book recommendations, and newspapers. Even the youngest writers can understand the purpose of these writing formats. And unlike the completion of a tedious worksheet, the creation of products like these is an authentic writing experience.

At the beginning of each Writing Box workshop, we ask writers to engage thoughtfully with a piece of literature or text as a prompt to their writing. When we talk about memoir, I might, for example, begin a workshop by talking about families. There are all different kinds of families. My mentor texts might include Susan Kuklin’s Families, Todd Parr’s The Family Book, and John Coy’s Their Great Gift: Courage, Sacrifice, and Hope in a New Land.

I would then read aloud Dan Yaccarino’s All the Way to America: The Story of a Big Italian Family and a Little Shovel. On the surface, this is an immigration story. Delving a little deeper, however, we discover that it is about what gets passed down in families: objects like shovels or pieces of clothing, genetic traits like curly hair, aptitudes like a talent for singing or drawing. As we reflect on the story, I chart these sorts of things on an easel pad. I may also suggest that we can write about what we hope to pass down to the next generation. (Some children do not have families where objects are passed down, are not with their biological parents, are with temporary caregivers, or have experienced devastating life events like evacuation or fires or homelessness). I may mention that I wish to pass down my love of reading or my knowledge about teaching.

As we begin to look at the details of setting up a Writing Box program, it’s important to recognize that as public librarians we are not imitating school practice. During summer reading programs, we are not teaching children to read, and during Writing Box programs, we are not teaching children to write. We know that self-selection of materials is a key component for readers who are choosing to read. Similarly, we are facilitating writing as a self-selected activity. On the other hand, partnering, collaborating, and consulting with literacy specialists, classroom teachers, and after-school programs is to be encouraged, as these educators enrich and support our own programs and practice. The public library can give children and adolescents opportunities to develop their literacy skills outside of the confines of school and the classroom. Just as librarians are charged with the mission of providing materials for the “freedom to read,” we must also provide the “freedom to write.” The skills required for the themes described in this book build upon each other. A writer who can draw can make a map, and a writer who can make a map can dictate labels for it. A writer who can draw and write can make both a map and a label. A writer who can draw and label maps can tell a story. A story can be told by drawing pictures and labeling with words, and a writer can dictate a story to accompany the pictures. As writers gain confidence in their own written words, the workshops ask for more and more writing as the weeks go on.