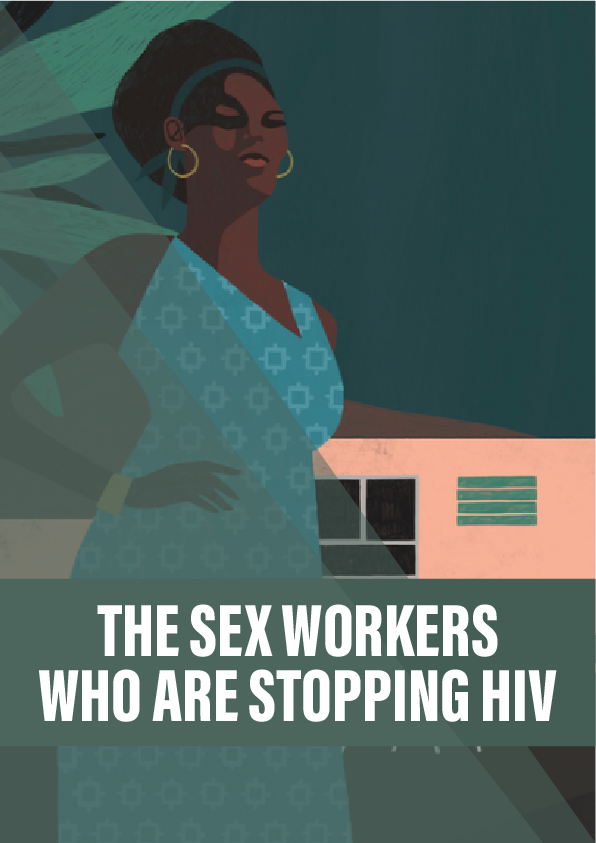

Sex workers in Mozambique are providing health support to those at the margins of society. They face political and financial challenges, but against the odds they are helping thousands. Jules Montague reports.

It’s late when we reach Inhamízua on the outskirts of the city. Stalls sell crackling chicken feet and sizzling plantain. Scores of men and women are gathered by a makeshift bar topped with corrugated steel. Spirits are high. The sound of laughter rises above the rumble of trucks trundling by.

Light from the gas station across the road illuminates the scene. Some of the women sit on white plastic chairs, nursing infants. It’s a nativity scene of sorts, set under coconut trees and soundtracked by Marrabenta-style dance music surging from a battered loudspeaker.

Luisa* and I walk behind the bar, through dried mud and over shards of glass and used condoms. We’re at the huts now. It’s 80 meticais for five minutes – about a pound. A bottle of beer in this town, to put things in context, costs 55.

In Beira, like everywhere else, sex sells – and there’s a good chance that HIV will be part of the transaction. Truckers drive here along the trade corridor that stretches from Zimbabwe’s eastern border. The end of their journey is a Mozambican port city where life expectancy is less than 50 and HIV rates are among the highest in the world. When they leave, that legacy often follows them.

One in ten adults in Mozambique is HIV positive, making the country’s HIV prevalence the eighth highest globally. But while the government has made progress on controlling the epidemic in recent years, reaching the marginalised along the Beira corridor has remained difficult.

How do you reach a population that is perpetually mobile? A population fearful of police intimidation, or of being found out by friends and family? In their eyes, they have little to gain from meeting you and everything to lose. To reach them, you need an innovative approach.

On we go, Luisa and I and the others, to place after place late into the night. Hotspots they call them, each one the same – makeshift bars with white plastic chairs, pumping music, overturned trucks, stacks of old tyres, broken beer bottles, and every time those huts out back.

Reference:

- A 2016 article from MSF, outlining the Corridor Project.

- A brief outline of Mozambique’s 40 years of independence, detailing past and present challenges.

- An overview of the Mozambican civil war, produced as part of the Mass Atrocities Research Program at Tufts University.