One in ten people struggle to recognise their emotions. New research suggests a vital link between our ability to sense our physical bodies and knowing how we feel.

Stephen has been married twice. Two wedding days. Two “I do”s. Yet Stephen has no happy memories from either – or, in fact, from the marriages or any of his relationships.

He met his first wife on a pre-nursing course when he was just 16. Six years later, they were married. Three years after that, they got divorced; she was never really the right one for him, he says. Almost two decades on, in 2009, he met his second wife through a dating site. He threw himself into the relationship and, the following year, with his father and her two adult siblings present, they married at the registrar’s office in Sheffield, where they both live.

He put on smiles for the wedding photos because he recognised that they were expected but, as he explains: “From an inner feeling point of view, anything I do that requires an emotional response feels like a fake. Most of my responses are learned responses. In an environment where everyone is being jolly and happy, it feels like I’m lying. Acting. Which I am. So it is a lie.”

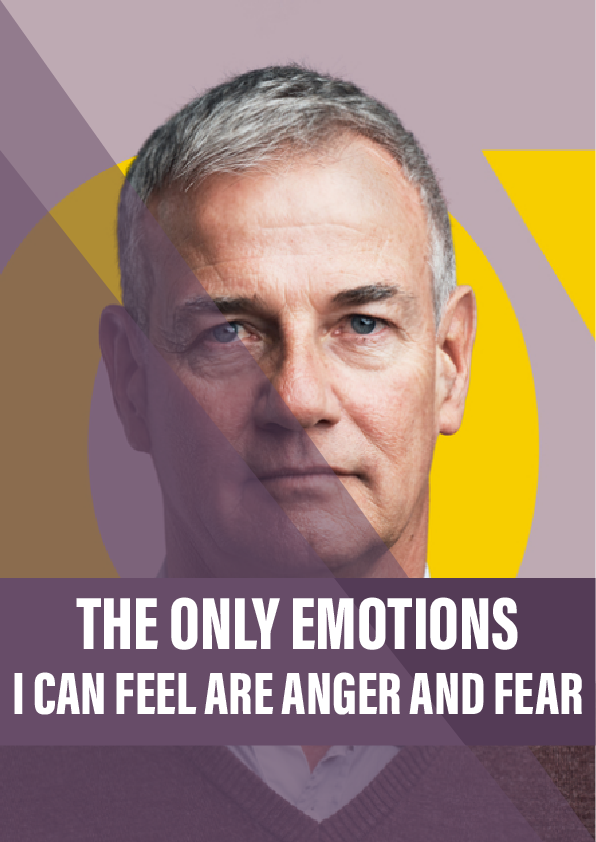

Happiness isn’t the only emotion that Stephen struggles with. Excitement, shame, disgust, anticipation, even love… he doesn’t feel these, either. “I feel something but I’m unable to distinguish in any real way what that feeling is.” The only emotions he is familiar with are fear and anger.

Such profound problems with emotion are sometimes associated with autism, which Stephen does not have, or with psychopathy, which he doesn’t have, either. Last year, at the age of 51, he finally learned what he does have: a little-known condition called alexithymia, a word made from Greek parts meaning, roughly, “no words for emotion”.

Despite the name, the real problem for people with alexithymia isn’t so much that they have no words for their emotions, but that they lack the emotions themselves. Still, not everyone with the condition has the same experiences. Some have gaps and distortions in the typical emotional repertoire. Some realise they’re feeling an emotion, but don’t know which, while others confuse signs of certain emotions for something else – perhaps interpreting butterflies in the stomach as hunger pangs.

Surprisingly, given how generally unrecognised it is, studies show that about one in ten people fall on the alexithymia spectrum. New research is now revealing what’s going wrong – and this work holds the promise not only of novel treatments for disorders of emotion, but of revealing just how the rest of us feel anything at all.

Reference:

- This 2016 paper by Rebecca Brewer, Richard Cook and Geoff Bird is a good introduction to alexithymia and its relation to interoception.

- Sarah Garfinkel’s three-dimensional model of interoception was described in a 2014 paper in Biological Psychology.

- A 2013 article by Bird and Cook explains how alexithymia is not necessarily part of autism and can be associated with various other conditions too.

- Childhood trauma is often associated with later psychological conditions such as depression and alexithymia.

- Researchers think we can learn a lot about emotion by studying psychopaths, who tend to have low empathy, guilt and remorse.

- In the UK and Republic of Ireland, the Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123. In the USA, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-TALK.