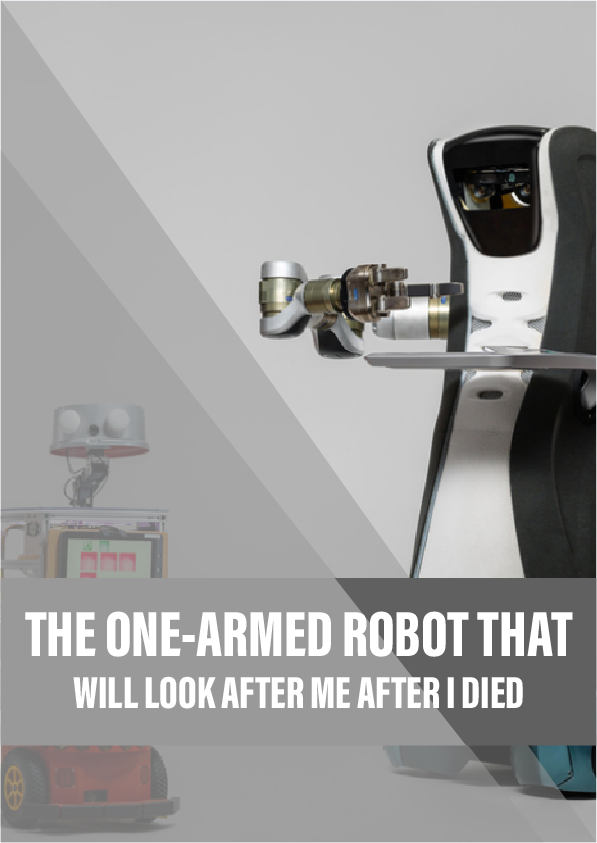

As old age approaches, Geoff Watts confronts an inevitable future in the care of robots. But that doesn’t mean he likes it.

The game is simple, designed for a child and intended to teach users about diet and diabetes. I sit opposite Charlie, my diminutive fellow player. Between us is a touch screen. Our task is to identify which of a dozen various foodstuffs are high or low in carbohydrate. By dragging their images we can sort them into the appropriate groups.

Charlie is polite, rising to greet me when I join him at the table. We proceed, taking turns, congratulating each other when we make a right choice, and murmuring conciliatory comments when we don’t. It goes well. I’m beginning to take to Charlie.

But Charlie is a robot, a two-foot-tall electromechanical machine, a glorified computer. It may move, it may speak, but it is what it is: a machine that happens to look humanoid. How can I ‘take’ to it?

Charlie’s intended playmates aren’t sixty-something Englishmen, they’re children. Children naturally interact with dolls, imagining them to be sentient beings. It’s a part of childhood. But I’m an adult, for God’s sake. I should have put away such responses to dolls… shouldn’t I?

The question is not ‘Do I want a robot companion to care for me?’ but ‘Would I accept being cared for by a robot?’

In truth my reaction to Charlie, far from being odd or childish, is pretty typical. Robots, of course, are hardly new. Over the last few decades we’ve had industrial devices that assemble cars, vacuum our floors and shunt stuff around warehouses. But the 2010s have seen a rise in the attention paid to robots of the kind that most of us still think of as robots: autonomous machines that can sense their surroundings, respond, move, do things and, above all, interact with us humans. We all recognise R2-D2, WALL-E and scores of their lesser-known kin. The unnerving thing is that their nonfictional counterparts are extremely close at hand. Some press stories are exotic – those about ‘sexbots’ being among the more sensational – but many have featured robots at the less hedonic end of social need: disability and old age.

This has set me wondering how I might cope with the experience – not for an hour or a day, but for months, years. Not tomorrow, but very soon, I will have to get used to the idea of living with robots, most likely when I’m elderly and/or infirm. Contemplating this, my line of thought has surprised and disturbed me.

Reference:

- ‘Animals Just Love You as You Are’: Experiencing Kinship across the Species Barrier – A broad overview of human-animal relationships.

- Does anyone want to talk to me? Reflections on the use of assistance and companion robots in care homes – A succinct position paper from Kerstin Dautenhahn and colleagues.

- Robots in Health and Social Care: A Complementary Technology to Home Care and Telehealthcare? –Reflections on the future of robots in this field.

- Do robots represent a viable and sustainable solution to the rapidly increasing social and care needs of an ageing population? – More reflections on the role of robots in social care.

- How Humans Respond to Robots: Building Public Policy through Good Design – One of a series Brookings Institution reports on the future of robotics, in this case around the integration of robotics into human life.