Meet the donors, patients, doctors and scientists involved in the complex global network of rare – and very rare – blood. By Penny Bailey.

His doctor drove him over the border. It was quicker that way: if the man donated in Switzerland, his blood would be delayed while paperwork was filled out and authorisations sought.

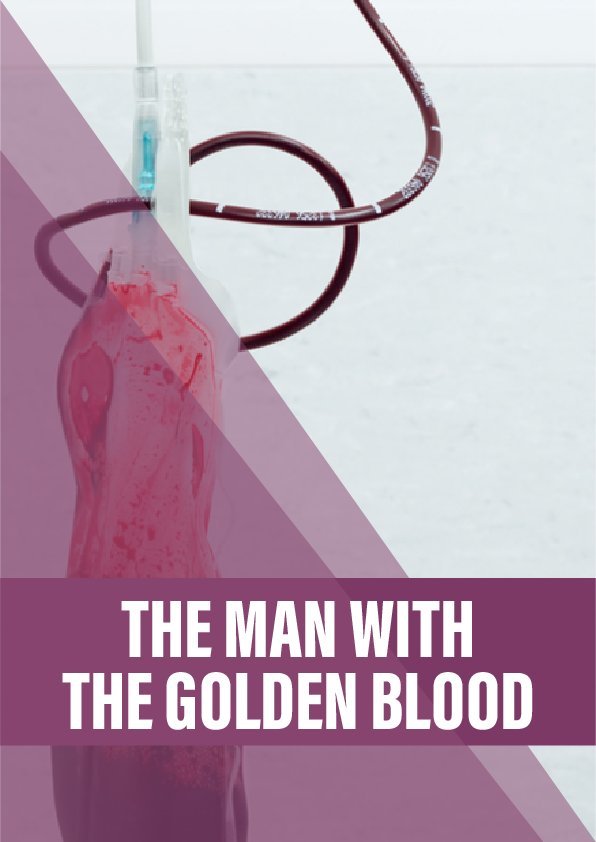

The nurse in Annemasse, France, could tell from the label on the blood bag destined for Paris that this blood was pretty unusual. But when she read the details closely, her eyes widened. Surely it was impossible for this man seated beside her to be alive, let alone apparently healthy?

Thomas smiled to himself. Very few people in the world knew his blood type did – could – exist. And even fewer shared it. In 50 years, researchers have turned up only 40 or so other people on the planet with the same precious, life-saving blood in their veins.

Red blood cells carry oxygen to all the cells and tissues in our body. If we lose a lot of blood in surgery or an accident, we need more of it – fast. Hence the hundreds of millions of people flowing through blood donation centres across the world, and the thousands of vehicles transporting bags of blood to processing centres and hospitals.

It would be straightforward if we all had the same blood. But we don’t. On the surface of every one of our red blood cells, we have up to 342 antigens – molecules capable of triggering the production of specialised proteins called antibodies. It is the presence or absence of particular antigens that determines someone’s blood type.

Some 160 of the 342 blood group antigens are ‘high-prevalence’, which means that they are found on the red blood cells of most people. If you lack an antigen that 99 per cent of people in the world are positive for, then your blood is considered rare. If you lack one that 99.99 per cent of people are positive for, then you have very rare blood.

If a particular high-prevalence antigen is missing from your red blood cells, then you are ‘negative’ for that blood group. If you receive blood from a ‘positive’ donor, then your own antibodies may react with the incompatible donor blood cells, triggering a further response from the immune system. These transfusion reactions can be lethal.

Because so few people have it, by definition, rare blood is hardly ever needed. But when it is, finding a donor and getting the blood to a patient in crisis can become a desperate race against the clock. It will almost certainly involve a convoluted international network of people working invisibly behind the bustle of ‘ordinary’ blood donation to track down a donor in one country and fly a bag of their blood to another.

Reference:

- Human Blood Groups by Geoff Daniels (2013, Wiley-Blackwell).

- The Blood Group Antigens Fact Book by Marion E Reid and Christine Lomas-Francis (2003, Academic Press).

- Blood group terminology from the International Society of Blood Transfusion.

- The International Blood Group Reference Laboratory, Bristol, UK.