When a volcano erupted on a small island in Indonesia in 1883, the evening skies of the world glowed for months with strange colours. Richard Hamblyn explores a little-known series of letters that the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins sent in to the journal Nature describing the phenomenon – letters that would constitute the majority of the small handful of writings published while he was alive.

During the winter of 1883 the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins descended into one of his periodic depressions, “a wretched state of weakness and weariness, I can’t tell why,” he wrote, “always drowsy and incapable of reading or thinking to any effect.” It was partly boredom: Hopkins was ungainfully employed at a Catholic boarding school in Lancashire, where much of his time was spent steering his pupils through their university entrance exams. The thought that he was wasting his time and talents weighed heavily upon him during the long, brooding walks he took through the “sweet landscape” of Ribblesdale, “thy lovely dale”, as he described it in one of the handful of poems he managed to compose that winter. He was about to turn forty and felt trapped.

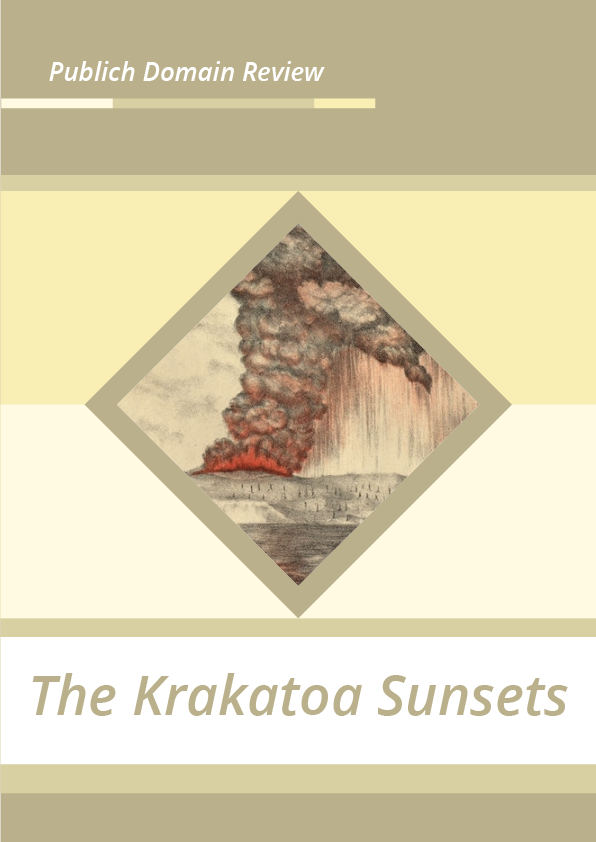

Such was his state of mind when the Krakatoa sunsets began. The tiny volcanic island of Krakatoa (located halfway between Java and Sumatra) had staged a spectacular eruption at the end of August 1883, jettisoning billions of tonnes of ash and debris deep into the earth. It’s upper atmosphere. Nearly 40,000 people had been killed by a series of mountainous waves thrown out by the force of the explosion: the Javan port of Anjer had been almost completely destroyed, along with more than a hundred coastal towns and villages. It“All gone. Plenty lives lost”, as a telegram sent from Serang reported, and for weeks afterwards the bodies of the drowned continued to wash up along the shoreline. Meanwhile, the vast volcanic ash-cloud had spread into a semi-opaque band that threaded slowly westward around the equator, forming memorable sunsets and afterglows across the earth’s lower latitudes. A few weeks later, the stratospheric veil moved outwards from the tropics to the poles, and by late October 1883 most of the world, including Britain, was being subjected to lurid evening displays, caused by the scattering of incoming light by the meandering volcanic haze. Throughout November and December, the skies flared through virulent shades of green, blue, copper and magenta, “more like inflamed flesh than the lucid reds of ordinary sunsets,” wrote Hopkins; “the glow is intense; that is what strikes everyone; it has prolonged the daylight, and optically changed the season; it bathes the whole sky, it is mistaken for the reflection of a great fire.”

In common with most other observers at the time, Hopkins had no idea what was causing the phenomenon, but he grew fascinated by the daily atmospheric displays, tracking their changing appearances over the course of that unsettled winter. At the end of December he collated his observations into a remarkable 2,000-word document, which he sent to the leading science journal, Nature. The article, published in January 1884, was a masterpiece of reportage, a heightened prose poem that mixed rhapsodic literary experimentation with a high degree of meteorological rigour:

Above the green in turn appeared a red glow, broader and burlier in make; it was softly brindled, and in the ribs or bars the colour was rosier, in the channels where the blue of the sky shone through it was a mallow colour. Above this was a vague lilac. The red was first noticed 45º above the horizon, and spokes or beams could be seen in it, compared by one beholder to a man’s open hand. By 4.45 the red had driven out the green, and, fusing with the remains of the orange, reached the horizon. By that time the east, which had a rose tinge, became of a duller red, compared to sand; according to my observation, the ground of the sky in the east was green or else tawny, and the crimson only in the clouds. A great sheet of heavy dark cloud, with a reefed or puckered make, drew off the west in the course of the pageant: the edge of this and the smaller pellets of cloud that filed across the bright field of the sundown caught a livid green. At 5 the red in the west was fainter, at 5.20 it became notably rosier and livelier; but it was never of a pure rose. A faint dusky blush was left as late as 5.30, or later. While these changes were going on in the sky, the landscape of Ribblesdale glowed with a frowning brown. (from G. M. Hopkins, “The Remarkable Sunsets”, Nature 29 (3 January 1884), pp. 222-23)