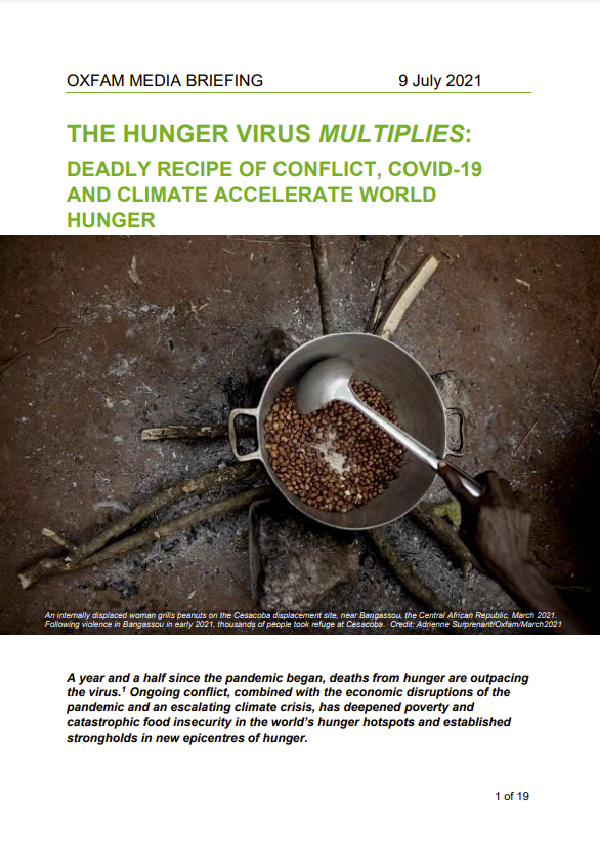

A year and a half since the pandemic began, deaths from hunger are outpacing the virus. Ongoing conflict, combined with the economic disruptions of the pandemic and an escalating climate crisis, has deepened poverty and catastrophic food insecurity in the world’s hunger hotspots and established strongholds in new epicenters of hunger.

“Before the war, I used to have my own small business, allowing me and my family to live in dignity, but war broke out in my country and took away everything from me. Rising food prices and the loss of my work made me unable to afford the living costs. On some nights, my five children have to go to bed hungry.” Wafaa, 38, a mother in Northern Syria

Last year, Oxfam warned in its report “The Hunger Virus” that hunger could prove even more deadly than COVID-19. This year, 20 million more people have been pushed to extreme levels of food insecurity, reaching a total of 155 million people in 55 countries.2 Since the pandemic began, the number of people living in famine-like conditions has increased sixfold to more than 520,000.

What we saw as a global health crisis has quickly spiralled into an inflamed hunger crisis that has laid bare the stark inequality in our world. The worst is still yet to come unless governments urgently tackle food insecurity and its root causes head-on. Today, 11 people are likely dying every minute from acute hunger linked to three lethal Cs: conflict, COVID-19, and the climate crisis.4 This rate outpaces the current pandemic mortality rate, which is at 7 people per minute.

The conflict was the single largest driver of hunger since the pandemic began, the primary factor pushing nearly 100 million people in 23 conflict-torn countries to crisis or worse levels of food insecurity. 6 Despite calls for a global ceasefire7 to allow the world to focus its attention on battling the pandemic, the conflict has gone largely unabated.

Even as governments had to find massive new resource flows to fight the Coronavirus, global military spending rose by 2.7% last year – the equivalent of $51 billion8 – enough to cover the $7.9 billion 2021 UN humanitarian food security appeal six and a half times over. Arms sales spiralled in some of the most conflict-torn countries battered by hunger.9 For instance, Mali increased its arms purchases by 669% since violence escalated in 2012.

The COVID-19 economic fallout was the second key driver of the global hunger crisis, deepening poverty and exposing the growing inequality around the world. The estimated number of people living in extreme poverty is projected to reach 745 million by the end of 2021, an increase of 100 million since the pandemic started. Marginalized groups, especially women, displaced people, and informal workers, have been hit hardest. 2.7 billion people have not received any public financial support to deal with the pandemic’s economic devastation.

Meanwhile, the rich continued to get richer during the pandemic. The wealth of the 10 richest people (nine of whom are men) increased by $413 billion last year – enough to cover the entire UN humanitarian appeal for 2021 more than 11 times over.

The climate crisis was the third significant driver of global hunger this year. Nearly 400 weather-related disasters, 14 including record-breaking storms and flooding, continued to intensify for millions across Central America, Southeast Asia, and the Horn of Africa, where communities were already battered by the effects of conflict and COVID-19-related poverty.

This brief explores how unabated conflict, economic shocks worsened by the pandemic, and the escalating climate crisis have pushed millions more people into extreme levels of hunger and how that number is likely to continue increasing unless urgent action is taken.

It looks at some of the world’s extreme and emerging hunger hotspots since last year’s Hunger Virus report, showing that hunger has worsened in almost all of them.