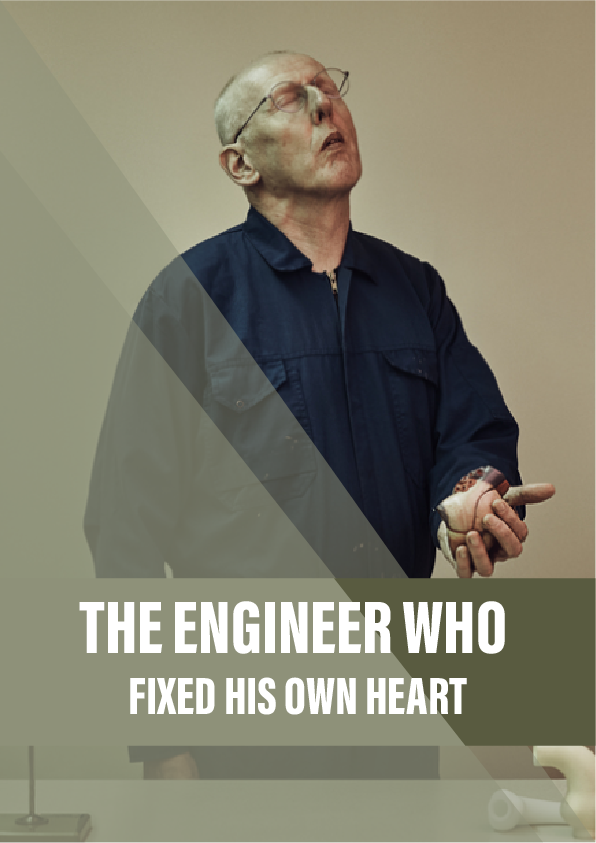

When Tal Golesworthy was told he was at risk of his aorta bursting, he wasn’t impressed with the surgery on offer – so he came up with his own idea. By Geoff Watts.

Lunchtime at a small medical engineering company in Tewkesbury. The entertainment thoughtfully laid on to garnish our sandwiches is a colourful video: a neat bit of cardiovascular surgery featuring someone’s heart and blood vessels.

Someone? Well, not quite anyone. The exposed and beating heart at which we’re gazing belongs to one of my dining companions. Tal Golesworthy, 60, is balding, quick-talking and often outspoken. He’s also – a clue here – tall, with unusually long fingers.

Getting on for 15 years ago Golesworthy learned that unless he was prepared to undergo major surgery on one of the vessels carrying blood away from his heart, he faced an increasing risk of premature death. He didn’t relish the prospect of an operation; but even more upsetting was the knowledge of what this particular procedure would involve.

Golesworthy is neither a doctor nor any kind of medical researcher. He’s an engineer. But with characteristic self-belief he reckoned he could devise a simpler and safer way of fixing his problem. And he did. He then persuaded a surgeon to take him seriously, became the guinea pig for the first operation, and now runs a company set up to manufacture implants like the one buried in his own chest. It’s been there for a decade, and it’s keeping him alive.

Golesworthy’s experience is notable for his persistence and single-minded determination. But there’s more to it than that. It raises questions about innovation in surgery, the acceptance of new procedures and the research required to test them. And it flags up the likelihood that other patients with other diseases are harbouring similarly ingenious or radical ideas.

If an aneurysm ruptures, the consequent internal bleeding is potentially fatal.

Tal Golesworthy has Marfan syndrome. The man memorialised by this name, Antoine Bernard-Jean Marfan, was a Paris paediatrician. In an 1896 case presentation he described a five-year-old girl with unusually long limbs, fingers and toes. It was not Marfan himself who named the condition, but one of his successors. Paradoxically, it is not even certain that the girl really was suffering from what now constitutes Marfan syndrome – but the name stuck.

The disorder is genetic in origin, either by inheritance or by spontaneous mutation. Besides their long, slender bones – and so their unusual height – people with the syndrome may have loose and flexible joints and various eye problems. The ultimate cause of all this is an error in the genes responsible for a protein called fibrillin, an essential component of the elastic fibres found in, among other tissues, the blood vessels. And this accounts for one of the biggest threats that Marfan syndrome presents to Tal Golesworthy and his fellow sufferers. The abnormality leaves one of their major vessels weakened and less able to cope with the strain imposed upon it by the pressure of the blood within.

One of the body’s biggest arteries, the aorta, receives blood straight from the left ventricle of the heart. The blood arrives not in a steady stream but in pulses. The aorta acts as a kind of hydraulic shock absorber, successively expanding and contracting as the pressure within it rises and falls. Any weakness in the wall of the aorta can allow the development of a balloon-like bulge, an aneurysm. For whatever reason, the weakest point of the aorta in people with Marfan syndrome is its root, the section adjacent to the valves guarding the exit from the left ventricle. If an aneurysm ruptures, the consequent internal bleeding is potentially fatal.

Reference:

- The most recent academic review of PEARS was published in September 2016.

- The Marfan Association UK has more information about Marfan syndrome.

- Exstent Ltd has more about Golesworthy’s invention and related research.