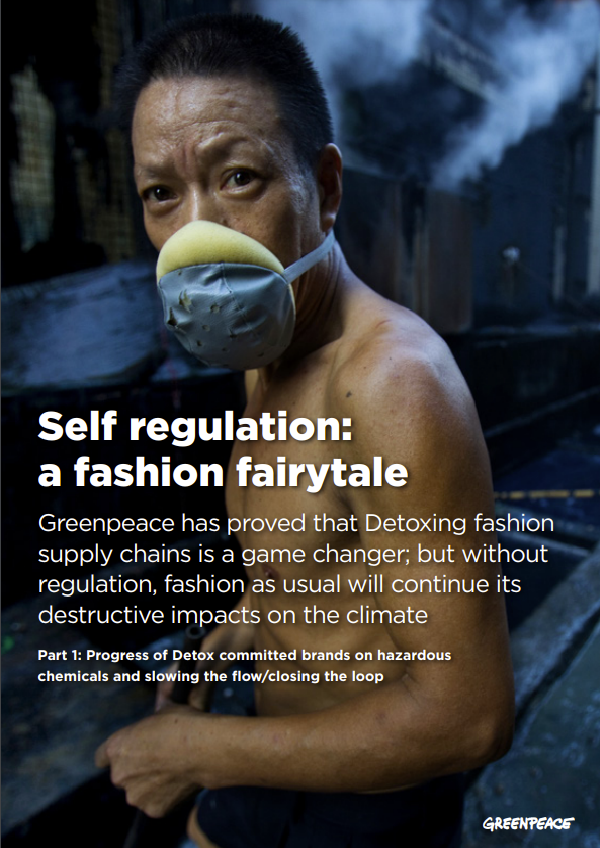

Ten years ago Greenpeace launched its Detox My Fashion campaign to address the problem of hazardous chemicals found by our investigators in effluent from textiles supply chain factories, in products, and in the environment, despite decades of regulation and corporate responsibility programs. With the help of hundreds of thousands of supporters and activists, the campaign secured global commitments to Detox from 80 companies and suppliers, to achieve zero discharges of hazardous chemicals in their supply chain manufacturing by 2020 and greater transparency about these hazardous chemicals discharges. In 2014, brands also committed to tackling the problem of over-production and waste and taking responsibility for the entire lifecycle of their clothes by “slowing the flow and closing the loop”.

One year after the 2020 deadline, we decided to see if these companies are still serious about their commitments. We’ve assessed the 29 global brands and retailers based on current information published on their websites – as a ‘blind check’2 – to see; firstly, whether the significant progress that had already been made on hazardous chemicals, evaluated in our 2018 report Destination Zero, is being maintained beyond the 2020 goal, and secondly if any effective measures have been adopted to reduce the overproduction of clothes and counter the ‘fast fashion’ trend. We provide an overview of these findings in Part I, and full details of the assessments in Part II.

The assessment of hazardous chemicals is mostly positive. On the whole, the momentum that was started by the Detox campaign is being maintained, with leading companies and several industry stakeholders taking responsibility for not only securing the 2020 goal but also promoting it to the entire textile sector (for example ZDHC, the group of textiles suppliers in Italy (Detox Consortium (CID)), OEKO-TEX, Bluesign). It is still a work in progress, and there is of course much more to be done, particularly the need to expand the Detox success story to the remaining 85% of the clothing market that did not commit to Detox. There are also signs of a new ‘race to the bottom’, with the same polluting practices we found in Asia and Central America during the Detox campaign now shifting to Africa when the clothing industry should be building on the best practice instead.

However, the overriding problem of overproduction and overconsumption in the fashion industry is impossible to ignore; all of the impacts on health, the environment, and people from fashion are multiplied by the growing volumes of clothing being produced and sold. The excesses, unfairness, and instability of fast fashion were cruelly exposed by the Covid pandemic. The extreme overproduction and overconsumption of fashion led to large quantities of clothes that were not being sold, some of which ended up being destroyed.

While businesses in Europe were sheltered from the impacts of Covid, global supply chains and the people dependent on them in Global South countries took the full economic impact of the pandemic when orders were canceled at suppliers, leaving workers unpaid and whole communities on the brink of survival.

Not surprisingly, the assessment of slowing down the overproduction of clothes is not so positive. The commitments to slow the flow and close the loop were mostly not implemented at anything like the scale required to truly address the problem. Most efforts have been aimed at closing the loop (circularity), but very little has been done to slow the flow of excess – leaving the fast fashion business model unchanged and maintaining its notoriety as a significant contributor to the global climate and biodiversity crisis.

Finally – and most importantly – we discuss whether what is essentially self-regulation is the solution to both of these problems and conclude that it is not. There will always be companies that will not take any action unless they are required to by regulation, whether that’s cutting corners on hazardous chemicals and water pollution in Africa or speeding up the turnover of “disposable” plastic clothing. There is therefore an urgent need for regulators to level the playing field, both locally (EU) and globally. Under pressure from the Greenpeace Detox My Fashion campaign, the Detox committed brands have proved that working with suppliers to eliminate hazardous chemicals in supply chain facilities can be done,3 but the majority of fashion brands are still not taking responsibility for this problem. Meanwhile, the fast-fashion business model which has led to “disposable fashion” being considered “normal” continues to dominate the production of clothes.

As this diagram shows, the environmental impacts of fashion are mostly taking place in the countries where all of our clothes are made – especially in East Asia, Asia, and Turkey: therefore a good part of the emissions and impacts in these countries occur because of consumption in the Global North.

In the face of the great planetary climate and biodiversity crises – with the third crisis of chemicals recently proposed – regulators must finally take responsibility for changing the way that fashion is made. Now is the time, as there is a unique opportunity, with two policy proposals currently being considered by EU regulators strategy for sustainable textiles, and a due diligence law on global supply chains. We are urging regulators to take bold action and serve notice to the fashion industry that business as usual cannot continue, and that companies using practices that devastate the planet and people’s lives will be regulated out of the market and held to account.

Source: Greenpeace (http://www.greenpeace.org)