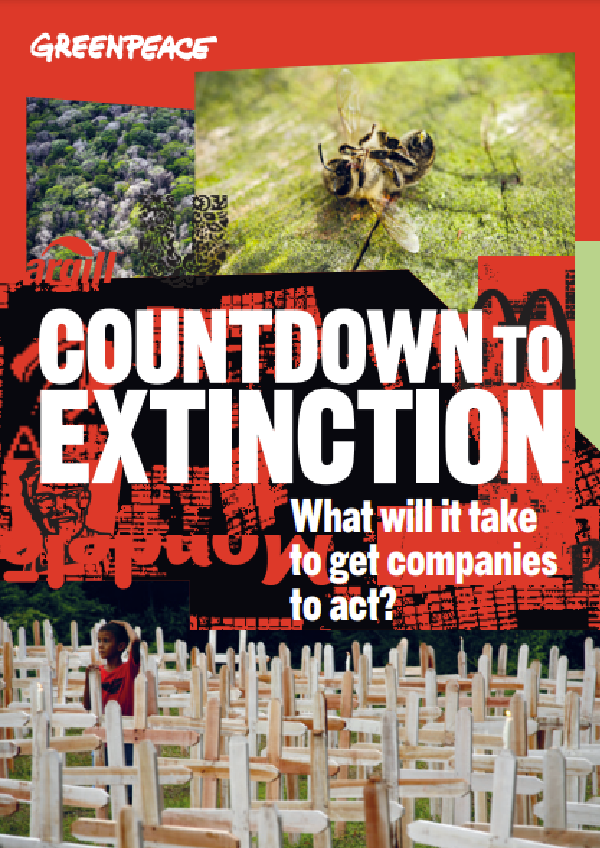

Climate change continues to present challenges to live and livelihoods globally and amplifies the problems humankind is already facing. The focus of this report is to outline the potential effects of climate change on plant pests, and hence on plant health, based on an analysis of scientific literature and studies that have investigated such aspects. A plant pest hereafter referred to as a “pest”, is any species, strain, or biotype of plant, animal, or pathogenic agent injurious to plants or plant products. Historic and current examples clearly show the extensive damage that can be caused by pest outbreaks. Warming facilitates the introduction of unwanted organisms; a single, unusually warm winter may be sufficient to assist the establishment of invasive pests, which otherwise would not be able to establish. In fact, the increased market globalization of recent years, coupled with increased temperatures, has led to a situation that is extremely favorable to pest movement and establishment, with concomitant increases in the risk of severe forest and crop impacts.

Studies have evaluated the effects of several atmospheric and climatic factors, including increased temperature, carbon dioxide, and ozone and changing water or humidity patterns, on the distribution, occurrence, and abundance of pests and the severity of the pest risk they pose. Most of the research has focused on managed systems (e.g. agricultural and horticultural crops, forest trees), whereas unmanaged systems have been more or less neglected. Many different research approaches have been used, ranging from conducting laboratory and field experiments to performing simulation studies of future pest risk.

Most studies, carried out with cereal and horticultural crops, indicate that, in general, pest risk from insects, pathogens, and weeds will increase in agricultural ecosystems under climate-change scenarios, especially in today’s cooler Arctic, boreal, temperate, and subtropical regions. This is also mostly true for pathogens and insect pests in forestry. For unmanaged systems, there are only a few research results available and hence no general conclusions can be drawn.

Preventive, mitigation, and adaptation measures to limit the international spread of pests through trade and travel are necessary. These range from measures such as use of healthy seed and planting material to the adoption of recent technological developments such as innovative methods of pesticide delivery. Short-and mid-term mitigation and adaptation options include measures such as the use of resistant varieties and the alteration of microclimate.

Despite the wealth of studies on climate-change biology, there are still prominent gaps in research into the impact of climate change on pests and on hence on plant health. These gaps include the effect of climate change on the effectiveness of management strategies, on below-ground pests, and on forestry and unmanaged systems. A long-term, multidisciplinary approach is needed that addresses the issues of developing as well as industrialized countries. International cooperation needs to be enhanced and investment should also be directed to capacity building, to ensure strong systems for pest risk analysis, surveillance, and monitoring.

To conclude, the evidence reviewed in this report strongly indicates that in many cases climate change will result in increasing problems related to plant health in managed (e.g. agriculture, horticulture, forestry), semi-managed (e.g. national parks), and presumably also unmanaged ecosystems. Adjustments in plant-protection protocols are already necessary because of recent climatic changes, but further adjustments will become increasingly crucial in the future, assuming the projected climate-change scenarios come true. Maintaining managed and unmanaged ecosystem services and products, including food, under climate-change conditions is of paramount importance. Preventive and curative plant protection is one of the key components needed to maintain and preserve current and future food security.