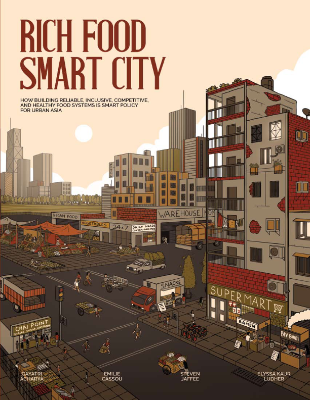

Well-functioning food systems are a critical part of the economy, identity, and human and environmental health of Asian cities. Healthy and sustainable food systems should actually be a defining aspiration of Asia’s dynamic cities given the importance of food to some of their leading concerns and priorities, including job growth and innovation, livability and sustainability, fiscal health, safety, and resilience. Moreover, with cities facing significant food-related challenges and opportunities, food ought to have the full attention of Asia’s city planners and leaders and food system matters should be a mainstream topic in urban planning and policy.

In much of emerging Asia, however food has been an urban policy and governance blind spot. Food systems have rarely been an area of urban policy focus and typically feature little in urban strategic and spatial planning. More often than not, urban food system issues are addressed in a piecemeal and reactive fashion. Different municipal government departments typically address the symptoms of food system problems independently, without coordination. Some actions by cities in other spheres may unintentionally be having adverse consequences on urban consumers and food business operators. While urban Asia has rightfully gained a reputation for innovation in many fields, in relation to urban food policy the region is lagging, badly, behind other regions. Of the more than 200 international cities that have signed the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, and thus committed to mainstreaming sustainable food measures in urban governance and policy, only three are in South Asia (Colombo, New Delhi, and Pune) and there are none in Southeast Asia.

One factor explaining the weak presence of food in urban policy making is institutional. Across Asia food policy has long been assumed to be the mandate of ministries of agriculture. In practice, these ministries have focused their policies on raising primary agricultural production, promoting rural development, and realizing national food security objectives. Urban areas have not generally featured in agricultural or natural resource planning. The development of institutions such as food safety agencies, nutrition-focused departments in health ministries, and market development authorities, suggests that food system matters are being handled by a disparate set of actors with little coordination. In addition, many topics of core concern in urban food systems, including food logistics, food safety, food entrepreneurship, dietary quality, and food waste are not assigned to a designated authority and hence have become areas of relative neglect. This institutional reality partly explains the paradox that urban food is at once “everybody’s business” and “nobody’s business.” It helps explain the urban policy and governance vacuums that persist in relation to food despite the range of stakeholders whose futures are tied to it—and the clear need for coherent multisectoral strategies and coordinated action.

Another important factor is the overwhelming number of issues that city planners and decision makers have to address in rapidly growing Asian cities. Many cities are encountering massive challenges associated with unplanned growth, including traffic congestion, air pollution, solid waste accumulation, underdeveloped physical infrastructure, and poor delivery of health, education, and other services. All of these are highly visible, and challenges for which urban residents are vocally demanding solutions. In contrast, many important foodrelated problems that are invisible because they are poorly monitored or measured are emerging steadily yet incrementally. As a result, they are not conjuring up a sense of urgency to the same degree that other city problems are. In some cases, this situation has given rise to a notion that urban food system matters can be dealt with later, when cities have become wealthier, and addressed after seemingly more urgent problems associated with early or rapid growth and development are tackled…..