Gender inequality is a social phenomenon in which men and women are not treated equally. The treatment may arise from distinctions regarding biology, psychology, or cultural norms prevalent in society. Some of these distinctions are empirically grounded, while others appear to be social constructs. Studies show the different experiences of genders across many domains including education, life expectancy, personality, interests, family life, careers, and political affiliation. Gender inequality is experienced differently across different cultures and also affects non-binary people.

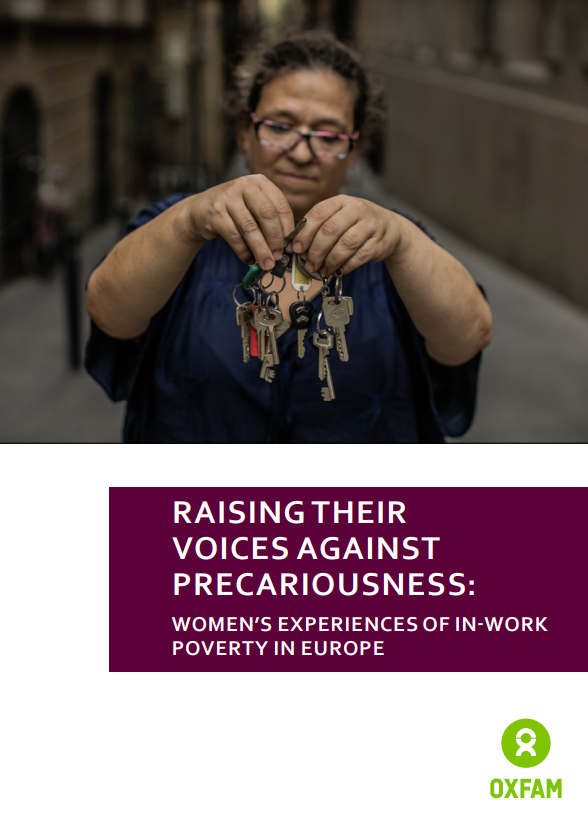

The world of work has undergone a radical transformation in the last 50 years. Women today are joining the workforce in greater numbers than ever before but, once there, still find themselves facing reduced opportunity, occupational segregation, increased harassment and violence, and are more likely to find themselves in uncontracted, insecure, and low-paid work than their male counterparts. In the EU-28, women are twice as likely as men to be in low-paid work.

Research into the impact of the 2008 economic crisis showed that, initially, it resulted in a narrowing of the gender gap by dramatically leveling down the working conditions faced by men. However, once the recovery phase began, men’s working conditions improved, while, in general, women’s either remained the same or continued to degrade. These dynamics seem to be reinforcing long-term trends around women’s involvement in the paid economy, marked by low pay and pay discrimination.

Once other factors have been accounted for, at least 10% of the pay gap women face in France and 14% in Spain can only be accounted for by discrimination. As an example, wage bumps conferred by discretionary, variable premiums and wage allowances are more likely to be given to men, partly due to the lower proportion of their time spent in unpaid caring and domestic work such as taking care of children or the elderly, which gives them greater flexibility, more availability to work long hours and more geographical mobility than women. In addition, risk premiums, which compensate workers for undertaking occupations considered risky for their health or physical wellbeing, are often not available to women workers who face equally hazardous working conditions.

As Mari, who is 43 years old and lives in a town near Madrid with her two children, told us: ‘A man who holds the same position and does the same tasks as me, earns more. This is a reality recognized by the company and confirmed by the confidential data delivered to the Works Committee. The company does it through salary supplements: the plus of availability and the so-called “extra activity of the month”. Even if men are not the ones covering extra times, they have these supplements included in their payroll.’

Discrimination and harmful social norms continue to devalue women’s abilities and contributions and limit their choice of professions. Gender inequality is compounded by discrimination and inequality linked to a range of social characteristics, including age, origin, race, ethnicity, household composition, and physical ability, each of which has a significant impact on women’s ability to find decent work. In particular, migrant women workers, and especially women born outside of the EU, are often among the most exploited and marginalized women workers. Younger employees are also the most likely to suffer in-work poverty, with women aged 15-24 facing the highest in-work poverty rate among all age groups. Generally speaking, ‘gender intensifies the disadvantages associated with inequalities and social identities.

Equally, in the EU-28 lone-parent families are as twice as likely to be facing poverty than households with 2 adults with children (21.6% compared with 10.4%). Over 80% of lone-parent families in Europe are headed by women. In France, a third of single mothers are at risk of poverty, while across the EU, almost two-thirds of single mothers report serious difficulty in making ends meet. The change these women need to see is grounded in policies that respond to both their gender and the other forms of disadvantage and discrimination they experience.