2 Everything (We Will Say) About Parsing

Parsing is the act of turning an input character stream into a more structured, internal representation. A common internal representation is as a tree, which programs can recursively process. For instance, given the stream.

23 + 5 – 6

we might want a tree representing addition whose left node represents the number 23 and whose right node represents subtraction of 6 from 5. A parser is responsible for performing this transformation.

Parsing is a large, complex problem that is far from solved due to the difficulties of ambiguity. For instance, an alternate parse tree for the above input expression might put subtraction at the top and addition below it. We might also want to consider whether this addition operation is commutative and hence whether the order of arguments can be switched. Everything only gets much, much worse when we get to full-fledged programming languages (to say nothing of natural languages).

2.1 A Lightweight, Built-In First Half of a Parser

These problems make parsing a worthy topic in its own right, and entire books, tools, and courses are devoted to it. However, from our perspective parsing is mostly a distraction, because we want to study the parts of programming languages that are not parsing. We will therefore exploit a handy feature of Racket to manage the transformation of input streams into trees: read. read is tied to the parenthetical form of the language, in that it parses fully (and hence unambiguously) parenthesized terms into a built-in tree form. For instance, running (read) on the parenthesized form of the above input—

(+ 23 (- 5 6))

—will produce a list, whose first element is the symbol ’+, second element is the number 23, and third element is a list; this list’s first element is the symbol ’-, second element is the number 5, and third element is the number 6.

2.2 A Convenient Shortcut

As you know you need to test your programs extensively, which is hard to do when you must manually type terms in over and over again. Fortunately, as you might expect, the parenthetical syntax is integrated deeply into Racket through the mechanism of quotation. That is, ’<expr>—which you saw a moment ago in the above example—acts as if you had run (read) and typed <expr> at the prompt (and, of course, evaluates to the value the (read) would have).

2.3 Types for Parsing

Actually, I’ve lied a little. I said that (read)—or equivalently, using quotation—will produce a list, etc. That’s true in regular Racket, but in Typed PLAI, the type it returns a distinct type called an s-expression, written in Typed PLAI as s-expression:

> (read)

– s-expression

[type in (+ 23 (- 5 6))]

‘(+ 23 (- 5 6))

Racket has a very rich language of s-expressions (it even has notation to represent cyclic structures), but we will use only the simple fragment of it.

In the typed language, an s-expression is treated distinctly from the other types, such as numbers and lists. Underneath, an s-expression is a large recursive datatype that consists of all the base printable values—numbers, strings, symbols, and so on—and printable collections (lists, vectors, etc.) of s-expressions. As a result, base types like numbers, symbols, and strings are both their own type and an instance of s-expression. Typing such data can be fairly problematic, as we will discuss later [REF].

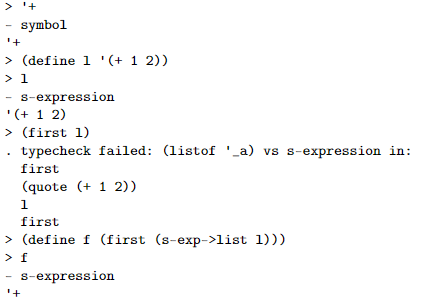

Typed PLAI takes a simple approach. When written on their own, values like numbers are of those respective types. But when written inside a complex s-expression—in particular, as created by read or quotation—they have type s-expression. You have to then cast them to their native types. For instance:

This is similar to the casting that a Java programmer would have to insert. We will study casting itself later [REF].