In 1585 the Englishman John White, governor of one of the very first North American colonies, made a series of exquisite watercolour sketches of the native Algonkin people alongside whom the settlers would try to live. Benjamin Breen explores the significance of the sketches and their link to the mystery of what became known as the “Lost Colony”.

As lucklesse to many, as sinister to myselfe. Such was the Elizabethan colonist John White’s gloomy assessment of his tenure as the first governor of Britain’s fledgling colony on Roanoke Island, Virginia. As White lived out his final days on an Irish plantation in 1593, he struggled to come to terms with his ambivalent legacy in the “Newfound Worlde.” Just eight years earlier, White had set out for North America as part of an expedition led by a fiery-tempered courtier named Sir Richard Grenville. This voyage was not without its challenges – White recalled laconically that in a battle with Spanish mariners he was “wounded twise in the head, once with a sword, and another time with a pike, and hurt also in the side of the buttoke with a shot.” Yet in this time White also witnessed natural marvels, helped build a new colony, and even celebrated the birth of his now-famous granddaughter, Virginia Dare, the first child of English/Christian parentage to be born on American soil. Ultimately, however, White’s ambitions ended in catastrophe, with the mysterious disappearance of the ninety men, seventeen women, and eleven children who comprised the Roanoke colony – a group that included his daughter and granddaughter.

In the centuries since White’s death, his story has diverged in an interesting way. Generations of schoolchildren raised in the United States can probably recall reading about the “Lost Colony” at Roanoke in textbooks. In these simplified accounts, White and his fellow colonists typically figure as doomed but visionary pioneers in a larger narrative of British-American exceptionalism.

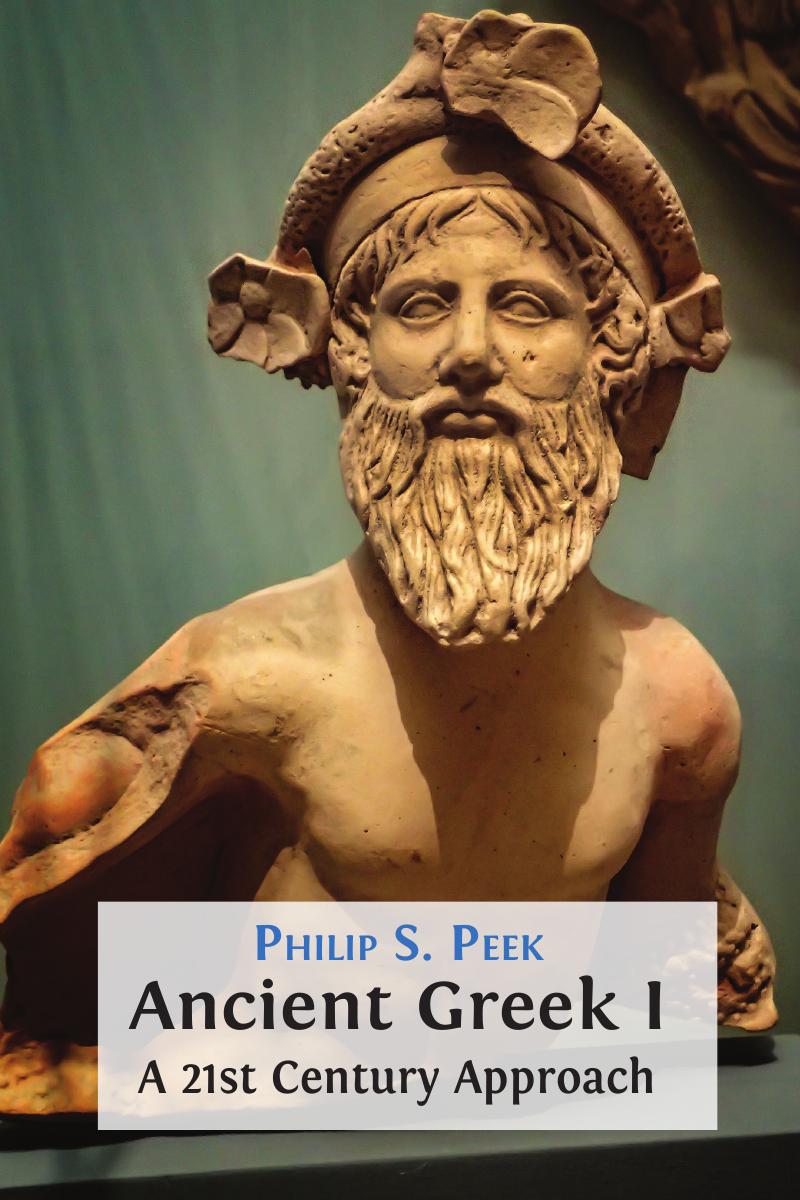

Among professional historians, White is equally famous, but for rather different reasons. In recent histories of colonial British America, it is John White the artist, rather than John White the colonial governor, who takes center stage. This is because White was a watercolor painter of extraordinary talent whose works number among the most remarkable depictions of early modern indigenous Americans ever created.

To be sure, many other European contemporaries of White offered up visual depictions of native Americans. Readers of André Thevet’s early account of Brazil Les singularitez de la France antarctique (Paris, 1557), for instance, could expect to be treated to renderings of Tupí Indians harvesting fruit, singing songs (complete with musical notation recorded by Thevet) and even munching casually on barbequed human thighs and buttocks.

Benjamin Breen is an Assistant Professor of history at UC Santa Cruz. He is the author of the book The Age of Intoxication: Origins of the Global Drug Trade (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).