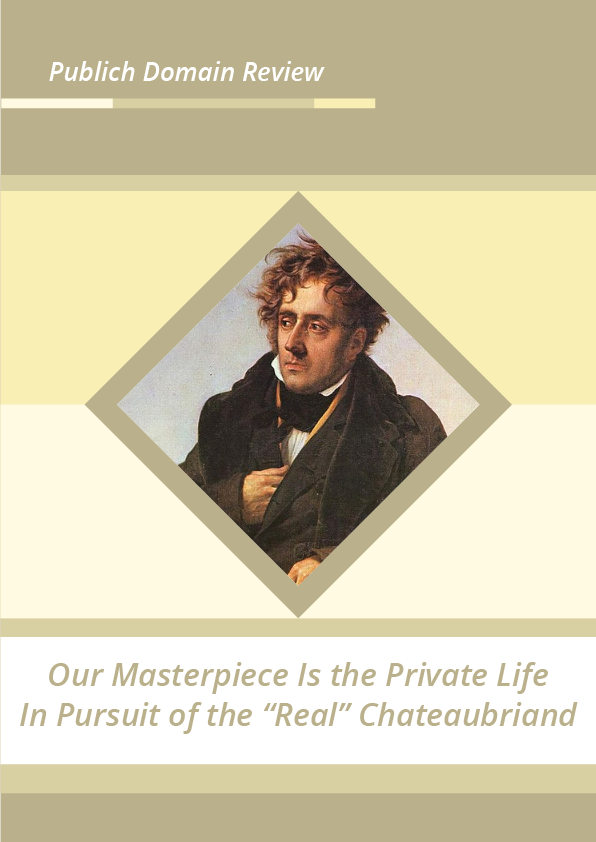

While nowadays he might be best known for the cut of meat that bears his name, François-René de Chateaubriand was once one of the most famous men in France — a giant of the literary scene and idolised by such future greats as Alphonse de Lamartine and Victor Hugo. Alex Andriesse explores Chateaubriand’s celebrity and the glimpse behind the public mask we are given in his epic autobiography Memoirs From Beyond the Grave.

In the spring of 1816, Alphonse de Lamartine was restless, ambitious, and twenty-five years old. Four years later, with the publication of his Méditations poétiques, he would be the toast of Paris, but for the moment he was just another provincial scribbler in the capital, too shy and proud, he says in his memoirs, to set foot in a literary salon. He therefore decided he would do the next best thing. He would travel four miles to the south, to the leafy Vallée aux Loups, and roam the forest, hoping to catch sight of one of the “great living figures of our era.”

This figure was François-René de Chateaubriand. A Bourbon royalist, a Catholic apologist, and the author of several popular books (including the novels Atala and René), Chateaubriand held a fascination for his contemporaries hard for us to understand. His fiction, which we often find high-flown and formal, they experienced as daring and wild; his conservative politics, which some of us regard with suspicion, were appreciated for being admirably idiosyncratic. Chateaubriand may have coined the word “conservative” in the political sense (by titling the Bourbonist journal he edited Le Conservateur), but he was also, in Anka Muhlstein’s words, “a liberal, open to modernity” (modernité being another word he is said to have coined).2

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, the French public looked to Chateaubriand as a man of principle, a defender of the freedom of the press, and an independent thinker unafraid to criticize both the tyrannical Napoleon and the disappointing Bourbon king Louis XVIII. In 1830, a few days before he resigned his seat in the Chamber of Peers — refusing to swear allegiance to the “usurping” king Louis-Philippe — a group of university students spotted him in the street and spontaneously hoisted him onto their shoulders, chanting “Long live freedom of the press! Long live Chateaubriand!” Yet, following his death in 1848, the reasons for his reputation soon grew vague. The entry for Chateaubriand in Gustave Flaubert’s Dictionary of Accepted Ideas, a book of bourgeois bromides compiled in the 1870s, might as well have been written yesterday: “Best known for the cut of meat that bears his name.”

Back in the 1810s, no one would have associated Chateaubriand with sirloin. He was famous and subject to fame’s magnifying lens. “I want to be Chateaubriand or nothing”, the fourteen-year-old Victor Hugo wrote in his diary, only a month or two after Lamartine, that fanboy avant la lettre, had gone to skulk around Chateaubriand’s house in the Vallée aux Loups. Adolescent identification with this tragic master of melancholy — who’d spent seven years of the 1790s exiled in England while several members of his family were guillotined under the Reign of Terror — drove many young romantics to a kind of madness, although none, so far as I know, acted on their madness with as much fervor as Lamartine.

Wandering the Vallée aux Loups, Lamartine found Chateaubriand’s house easily enough. He was unable to see anything over the garden wall, however, and so he climbed into some trees overlooking the property. “I stayed sitting in the branches, hidden by the leaves, from noon until night, but to no avail”, he recalls in his memoirs; “I saw nothing moving except a trickle of water that sparkled as it sputtered from a stucco fountain, and the shadows that shifted and spread over the grass beneath the weeping willows.” When night fell, Lamartine was forced to return to Paris. But he had not abandoned his folly. By noon the next day, he was back, like Calvino’s baron, in his perch among the branches:

Half the afternoon elapsed in the same silence and disappointment as the afternoon before. Finally, at sunset, the door of the little house turned slowly and noiselessly on its hinges. A short man in black clothes, with broad shoulders, skinny legs, and a noble head, emerged, followed by a cat, to whom he threw balls of bread to make it gambol on the grass. Soon, both cat and man were swallowed by the shadows of an alley of trees; the undergrowth hid them from my sight. A moment later, the black clothes reappeared at the threshold of the house, and locked the door. This was all I saw of the author of René, but it was enough to satisfy my poetic superstitions. I went back to Paris dizzy with literary glory.

In later life, Lamartine’s fervor for Chateaubriand inevitably cooled. He could no longer see what had once excited him in the writing, which he now found too theatrical (“always treading the boards”).7 As for the man, Lamartine would be introduced to him several times in the embassies and palaces of Paris, London, and Rome. “But the Chateaubriand of the Vallée aux Loups has for me always been the real Chateaubriand”, he concluded: “The person, rather than the persona.”