I thought I was dying.

During the day, I was so tired my knees would buckle. Driving the car, my head would dip and then I would catch myself. My face was lined with exhaustion.

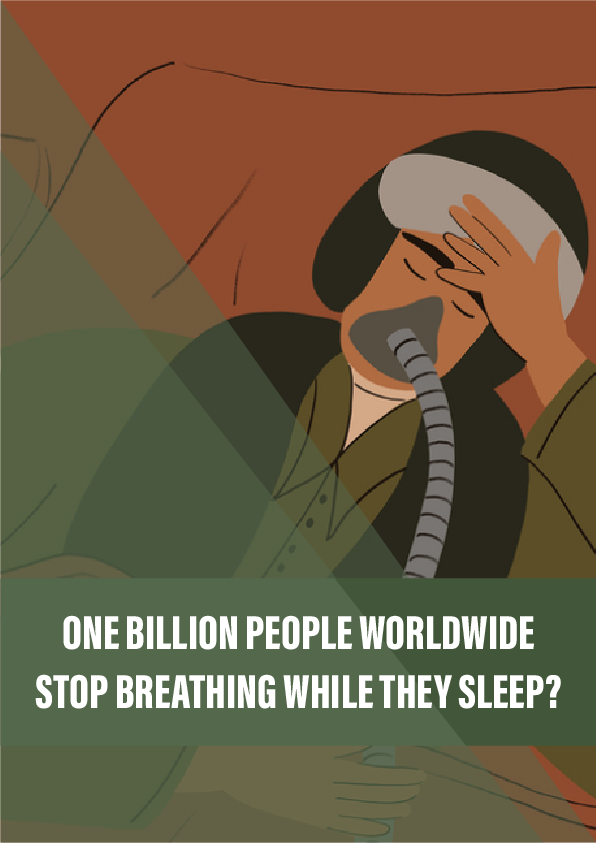

At night, I would sleep fitfully, legs churning, then snap awake with a start, gasping for breath, heart racing.

My doctor was puzzled. He ordered blood tests, urine tests, an electrocardiogram – maybe, he thought, the trouble was heart disease; those night-time palpitations…

No, my heart was fine. My blood was fine.

He ordered a colonoscopy. It was late 2008 and I was 47 years old – almost time to be having one anyway. So I forced down the four litres of Nulytely to wash out my intestines so a gastroenterologist could take a good look inside.

My colon was clean, the doctor told me when I regained consciousness. No cancer. Not even any worrisome polyps.

However. There was one thing.

“While you were under,” he said, “you stopped breathing at one point. You might want to check that out. It could be sleep apnoea.”

I had never heard of it.

Sleep is marked by dynamic changes throughout the body. It’s made up of different phases, and as you move through them, your breathing, blood pressure and body temperature will all fall and rise. Tension in your muscles mostly stays the same as when you are awake – except during REM phases, which account for up to a quarter of your sleep. During these, most major muscle groups ease significantly. But if your throat muscles relax too much, your airway collapses and is blocked. The result is obstructive sleep apnoea – from the Greek ápnoia, or ‘breathless’.

Reference:

- An NHS overview of sleep apnoea, describing how to diagnose it and treat it.

- An article from Johns Hopkins Medicine that discusses the dangers of leaving sleep apnoea untreated.

- The first study to look at the global prevalence and burden of sleep apnoea, published by Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

- A history of the CPAP machine, from the US National Sleep Foundation.