I was born close to the city of Zwickau in a small village in Saxony where my father was the local priest.

Although the Berlin Wall came down just three years before I was born, this event seems very distant to me today. The very notion of growing up in a divided Germany now seems almost absurd to me. Many young adults of my generation find it difficult to understand what reunification actually meant for the people who had lived in some cases for decades in a divided Germany.

To get a clearer idea of what the fall of the Berlin Wall meant for my family, I asked my father to tell me what he remembers.

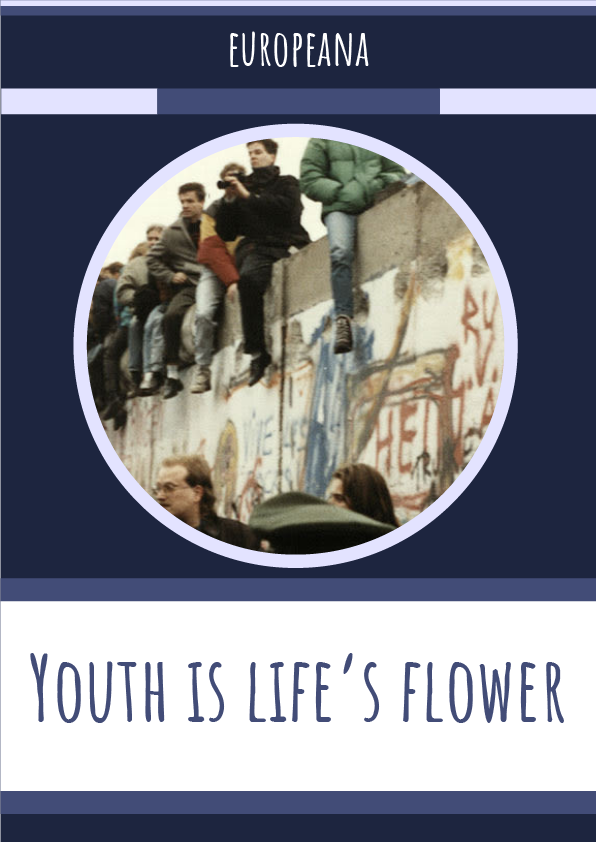

For young people today, this is what they know of the Berlin Wall – something that has been taken down, a pile of scrap concrete.

They don’t remember this…

When the Wall came down, it was a surprise to my father too. Beforehand, he’d been talking to my uncle who’d invited him and his family to join him in the West, but my father replied: ‘If every doctor and priest leaves the country, what will happen then? Who will be able to give the people hope?’

And so they stayed.

He believed that the Berlin Wall would soon fall anyway – at the latest by 1995 when the Warsaw Pact was set to celebrate its 50th anniversary. But before that could happen, the Two Plus Four talks were held in 1990 which eventually led to freedom.

Many East Germans crossed the Austrian border into the Federal Republic, simply abandoning their Trabant cars at the border. My father could tell me plenty more about this time because in September 1989 he drove a caravan with a friend down to the Greek border. In the Czech Republic, they followed the trucks and trailers of the German Red Cross down to Lake Balaton where they were searching for fellow Germans in the camps who were waiting to travel to the West.

When the Wall did actually come down, my father was at home watching TV.

On 9 November 1989, he was watching the news bulletin in which it was reported that the border was to be opened. He said, ‘I sat down on the floor right in front of the television and cried my eyes out in joy at the opening of the Wall because I knew what the falling of the Iron Curtain meant for us and our freedom.’

He has no more detailed memories of this time and I, his daughter, was yet to be born. But for the next generation, including myself, the fall of the Berlin Wall brought with it an incredible increase in freedom and independence.

His lasting memory now is of how hard it was to take everything in. About six months later, he told me, he was on the Ku’damm in West Berlin where, standing in the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche, he felt the need to scratch his knuckles against the wall of the church until he was in pain and bleeding – so that he could really feel it for himself.

‘The border’s gone – you really are on the other side. We’re free for now and the foreseeable future, and Europe is a free alliance of peoples, and not one based on ideology. I’m a committed European. And I have cosmopolitan attitudes and beliefs. And if it ever proves necessary to defend this freedom and to fight for it, then I will.’

The fact that my father remembers this moment so clearly after nearly a quarter of a century shows just how significant this peaceful revolution was both for the people who lived through it and for the history books.