What does the future sound like? In the early 20th century, one answer rang out from Luigi Russolo’s intonarumori — lever-operated machines designed to pop, sough, shriek, and shock. Peter Tracy explores the ambitions behind Italian Futurism’s experiments with noise and the sensory, spiritual, and political affinities of this radical new music.

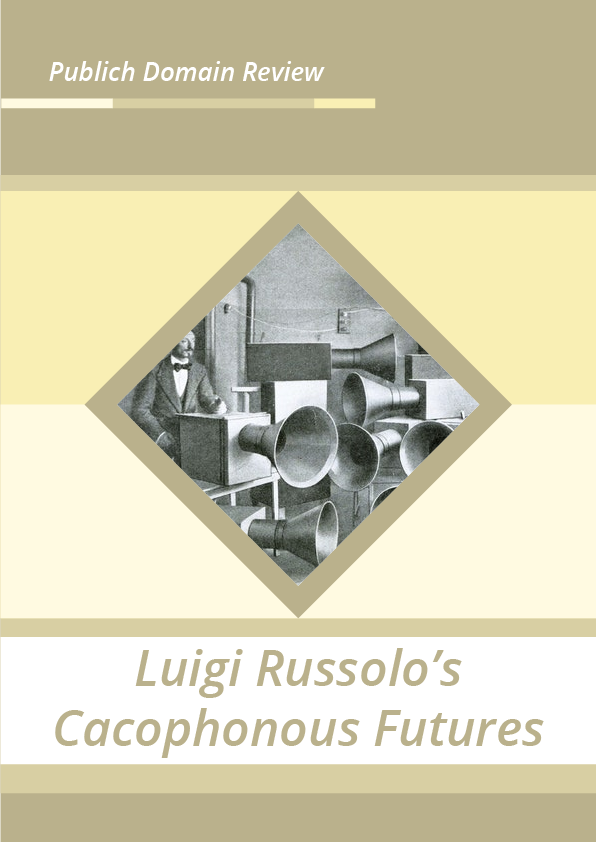

Luigi Russolo (1885–1947) was well into a successful painting career when he turned to music in his 1913 manifesto The Art of Noises (L’arte dei rumori). Announcing an intention to “enlarge and enrich the field of sound”, the Futurist polymath waxed poetic about the modern city’s sonic landscape — “the throbbing of valves, the bustle of pistons”, and “the shrieks of mechanical saws”. For Russolo, the noisy nature of everyday, industrializing Europe offered new ways of perceiving the acoustic world and a means of shaking concert music loose from its stagnant orchestral roots. With significant help from his assistant, Ugo Piatti, Russolo set out to put these ideas into practice, working day and night to “achieve the great ideal of a complete orchestra of noise instruments [intonarumori]”. Within three months, they had built their first creation, a “burster” (scoppiatore), and premiered it before an audience of two thousand at Teatro Storchi in Modena, Italy. Meant to mimic a car engine’s sputter, the instrument, by all appearances a simple wooden box with an enormous speaker cone attached, had a playable range between two octaves, modulated by a crank and lever. This “burster” was soon followed by a “hummer”, a “rubber”, which evoked spatulas scraping rusty pans, and the “crackler” — a sonic chimera sounding like something between a mandolin and a machine gun.

Little remains today of Russolo’s instruments beyond scattered diagrams and photographs, which have been used on multiple occasions to create playable replicas. Aside from a fragment of the score for Risveglio di una città, none of Russolo’s compositions for the intonarumori survive. Yet, miraculously, two gramophone recordings were produced by Russolo and his brother Antonio in 1921 and have been successfully preserved. In these grainy time-capsules, the intonarumori seem to be in conflict with one another, battling for sonic space alongside traditional instruments at what sounds like the end of a long tunnel. In Corale, an asinine, plodding orchestral score is rendered unsettling by the violent roar of an unidentifiable machine. Serenata features even less of the intonarumori, but their occasional presence turns a sentimental serenade of strings and woodwinds into a carnivalesque nightmare. Tempered by the presence of instruments from the past and by the limits of contemporary technology, the “noise intoners” nevertheless make their intense energy felt through Russolo’s soundscapes.

In an interview some forty years after his 1915 encounter with the music of the Italian Futurists, composer Igor Stravinsky recalled the event as, at best, an intriguing oddity:

On one of my Milanese visits Marinetti and Russolo, a genial quiet man but with wild hair and beard, and Pratella, another noisemaker, put me through a demonstration of their “futurist music.” Five phonographs standing on five tables in a large and otherwise empty room emitted digestive noises, static, etc. . . . I pretended to be enthusiastic and told them that sets of five phonographs with such music, mass produced, would surely sell like Steinway Grand Pianos.

Stravinsky’s reaction was mild when compared to that of the international press: one correspondent for a Paris newspaper described a concert of the intonarumori as “an impressive simultaneity of bloody faces and noisy enharmonics in an infernal din”.7 Yet the musical inventions of Russolo did not fail to find admirers. Indeed, the composer Edgard Varèse was highly enthusiastic about Russolo’s musical and theoretical works, as were later composers such as Pierre Schaeffer and John Cage, and visual artists like Piet Mondrian. What was still unknown to Stravinsky in 1915, however, would become common knowledge by the mid-twentieth century: the sonic revolution that Russolo and his fellow Futurists sought was uneasily compatible with the ritualized, martial violence celebrated by Italian Fascism.