Max Adams, author of The Prometheans, looks at the art of John Martin and how in his epic landscapes of apocalyptic scale one can see reflected his revolutionary leanings.

Max Adams was born in London in 1961 and after more than twenty years as an archaeologist turned to writing. His first major biography, published in 2005, aimed to rescue the reputation of a neglected naval hero, Admiral Collingwood (Weidenfeld 2004). His group biography of artist John Martin’s circle, The Prometheans was published in 2009 and was a Guardian Book of the Week. Max’s third neglected-Geordie biography, just completed, is a life of the first Englishman of whom one could write a biography: Oswald, the Dark Age Northumbrian king and saint. Max is a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at the University of Newcastle. His website: www.theambulist.co.uk/

John Martin, born in the week that the Bastille was stormed in July 1789, was an instinctive revolutionary. His generation may have suffered from a misty-eyed envy of new-found liberties in America and France, but they understood what practical revolution might mean at home and they strove to achieve liberation from repression and tyranny without bloodshed; very largely they succeeded.

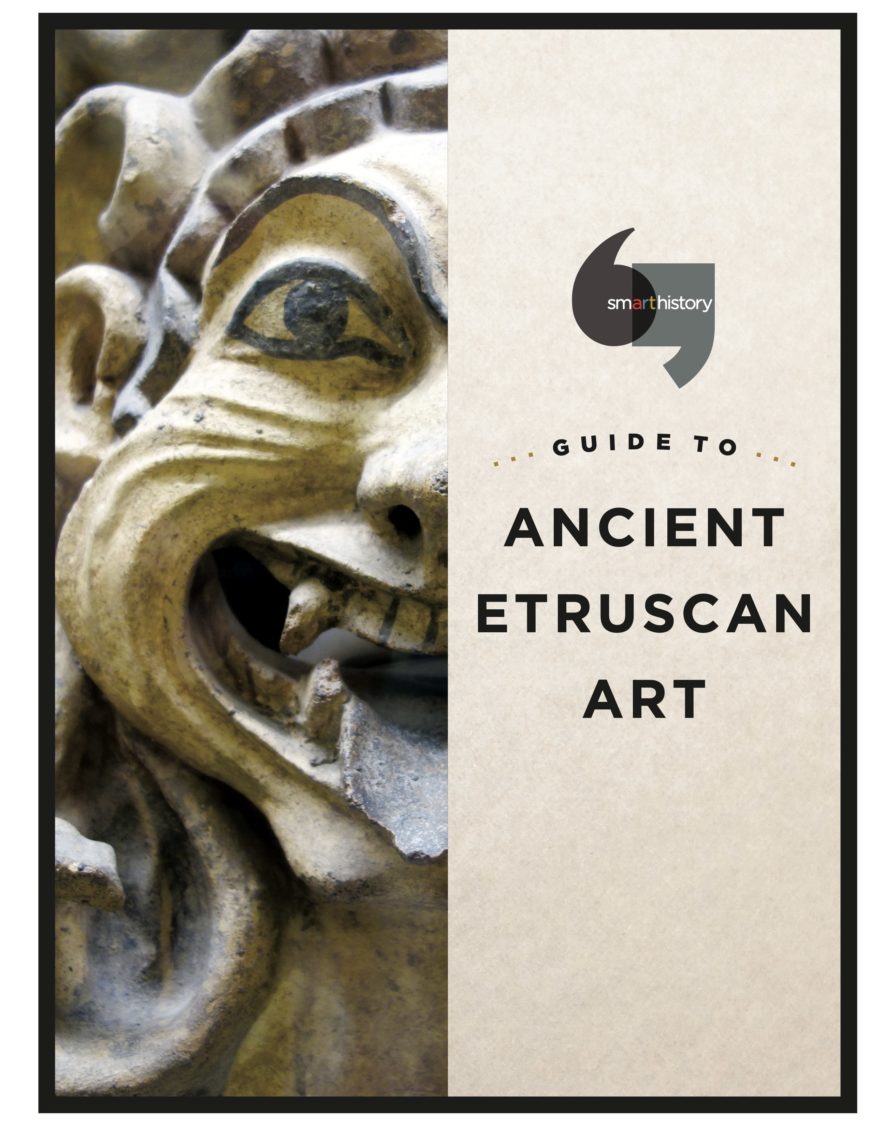

Martin has often, and wrongly, been seen as a religious fanatic by a comprehensive misunderstanding of his paintings and by false association with his schizophrenic arsonist brother. He has also been portrayed as a Luddite (by critics who should have known better) and by Ruskin, a late contemporary, as a mere artisan in lamp-black. Poor Martin. Despite his very evident technical deficiencies as a painter – he inevitably suffers by comparison with his friends and contemporaries Turner and Constable – he was equally adept at creating a theatrical sense of a world undergoing irreversible change, and more fervent than either in his desire to be an engine of that change. If there were dramatists better placed to portray the dilemmas of the human condition, and one immediately thinks of Shelley and Byron, of Delacroix and Dickens, no-one came closer than Martin to designing the perfect sets on which to act out the drama: he was the supreme architect and engineer of the sublime.

To start at the curtain’s uncertain opening, we see Martin, a Geordie ingénue with a chip on his shoulder, arrive in London to find that its streets are not paved with gold but with beggars. He makes his debut in the greatest city on earth in 1806, the year in which Pitt the Younger and Charles James Fox die and in which Nelson’s pickled body is carried up the Thames in mawkish pomp. Martin struggles against more proficient competition: has insufficient imagination in his mental palette other than to paint the misty blue hills of his native Northumbria and dream of maidens in skimpy veils straight out of Ovid. By 1812 his mood has darkened: his radical friends the Hunts have been jailed for seditious libel (the Prince Regent was a fat, useless libertine, a drain on the treasury and a traitor to his Whig friends but saying so in the pages of the Examiner in such terms was asking for trouble); the first global war showed no sign of ending, nor did the horrors of wage-labour poverty. Caricaturists had a field day: they could not be imprisoned. Martin’s response was weightier, loftier. His Sadak of 1812 is a dark, portrait-format theatre flat of abysmal fire in which the struggling righteous loner (his friends the Hunts, the beggar, or Martin himself: take your pick) faces alpine odds in seeking the Waters of Oblivion.