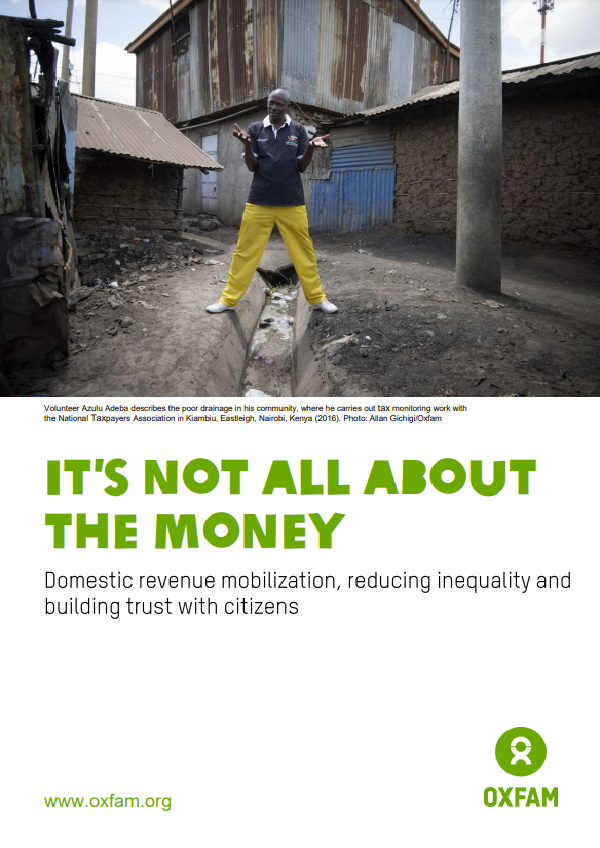

It’s not all about the money

Domestic revenue mobilization, reducing inequality and building trust with citizens

Governments need more domestic revenue to fund their own development goals, but it won’t come from squeezing the poor. It’s not only about collecting more. It’s about how that revenue is collected (i.e. who pays). The path to successful domestic revenue mobilization (DRM) starts with the political commitment to reducing inequality and building trust with citizens.

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, or national), and tax compliance refers to policy actions and individual behaviour aimed at ensuring that taxpayers are paying the right amount of tax at the right time and securing the correct tax allowances and tax reliefs. The first known taxation took place in Ancient Egypt around 3000–2800 BC. A failure to pay in a timely manner (non-compliance), along with evasion of or resistance to taxation, is punishable by law. Taxes consist of direct or indirect taxes and may be paid in money or as its labour equivalent.

Low income (LIC) and low-middle income countries (LMICs) are on pace to collect public revenues of about $444 per person annually by 2020. This is just over $1 per person per day.2 Compared with $16,200 per person in richer countries (2015), the need for greater DRM is clear. If LICs and LMICs improve revenue-to-GDP by an extra 2 percentage points by 2020, their annual public revenues would increase collectively by $144bn3—more than total development aid in 2016. This is simple math, but achieving it is no simple task. In most developing countries, DRM remains insufficient and worse, it is becoming less fair. The imperative to improve how public revenues are collected has never been more apparent.

In 2017, 82% of all wealth created went to the top 1%, while nothing went to the poorest bottom half of humanity. This kind of extreme inequality intensifies the core challenges for DRM, worsened by the lopsided political power it constructs—which has resulted in laws, policies and loopholes that undermine effective tax systems.

Governments and donors must confront the political-economy obstacles to fairer, more transparent, and more accountable revenue systems. In the end, the big dividends from investing in DRM should not be just more money—but fairer revenue systems and stronger citizen–state compacts.

Without an equitable approach to DRM, it will be just another acronym in the development dictionary.