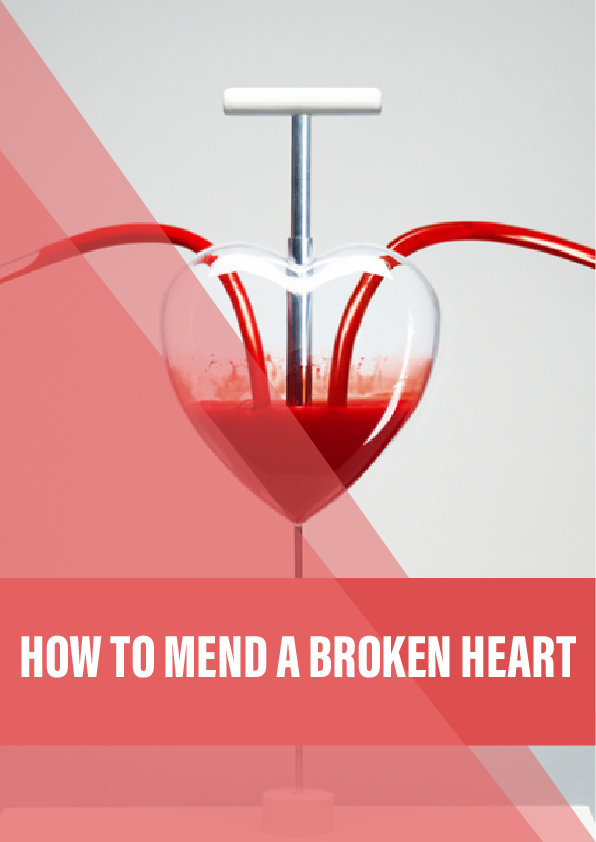

The need to mend broken hearts has never been greater. But what if we could simply manufacture a new one? Alex O’Brien studies the legacy of Texan surgeons and artificial hearts.

Haskell Karp was 37 when he suffered his first heart attack, and over the next ten years he suffered a variety of related problems. By 1969 even the slightest effort, like combing his hair or brushing his teeth, would bring on chest pain or extreme shortness of breath. There are four grades of heart failure under the classification determined in 1928 by the New York Heart Association; Karp’s was classified as grade IV, the most severe.

The surgeon who treated him at St Luke’s Hospital, Texas, in 1969 was an energetic man called Denton Cooley. “The man had a big dilated heart and I hoped we could reduce the size of that heart, so it could regain some of its own function,” says Cooley. But Karp did not respond well to the treatment; half of his heart was beyond repair. Cooley had expected this. He’d discussed it with Karp before the surgery: “I don’t think your heart’s going to be strong enough to tolerate this operation,” he’d told him. But Cooley had made a suggestion: if Karp’s heart were to be too weak at the end of the operation, how about taking a replacement – an experimental artificial heart they’d been developing in the lab.

The mechanical heart was a temporary ‘bridge’, intended to provide additional time for patients waiting for a donor heart to become available. It had an implantable part, larger than a human heart, connected to an exterior console the size of an upright piano powering it. The contraption drove compressed air through two hoses made of silicone and fabric (which entered the patient’s body below the ribcage) and into the chambers of the artificial heart: one side a left pump, the other a right, each with a balloon inside. When the chamber filled with blood, the balloon filled with air and pushed the blood out, keeping Karp alive.

Reference:

- 100,000 Hearts: A surgeon’s memoir – by Denton Cooley

- King of Hearts – The true story of the Maverick who pioneered open heart surgery – by G. Wayne Miller

- Flatline: This wonderful 7min film tells the story of Bud Frazier and Billy Cohn’s work on the pulseless artificial heart. An extended version of the short film HEART STOP BEATING (featured at the Sundance film festival in 2012).

- A short documentary on Bud Frazier by the Texas Heart Institute.

- Documentary: Living without a pulse