In this report by Greenpeace Spain and Greenpeace UK, we chart the evolution of the North Atlantic shark fishery, tracking the distressing downward trajectory of shark populations and the consequent impacts on ocean health.

We reveal the failure of policymakers to act responsibly, exposing their unwillingness to prioritize ocean health and the communities who depend on it, whilst disclosing the extent to which industry dominates decision-making in pursuit of profit.

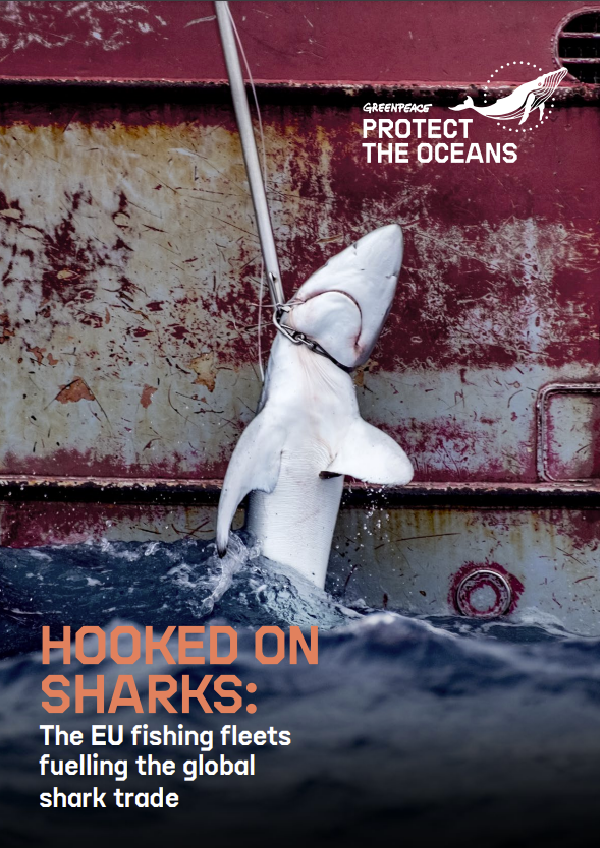

We examine the industry’s ever-more efficient and destructive approach to fishing, including the targeting of juvenile sharks and the increasing efficiency of fishing gear.

We propose recommendations that will turn the tide, focusing on the responsibility of the EU to adopt more progressive policy positions in relevant multilateral fora and leading the way in ocean protection.

Main findings

- EU distant water fleets from Portugal and Spain are consistently fishing juvenile (baby) shark breeding grounds.

- The EU, along with the Spanish and Portuguese governments, have both consistently resisted attempts to improve the management of this fishery because of lobbying by their respective fishing industries, despite claiming to be global ocean champions on the world stage.

- On an average fishing day in the North Atlantic, there are a shocking 1200kms of fishing cables in the water, with an estimated 15000-28000 hooks.

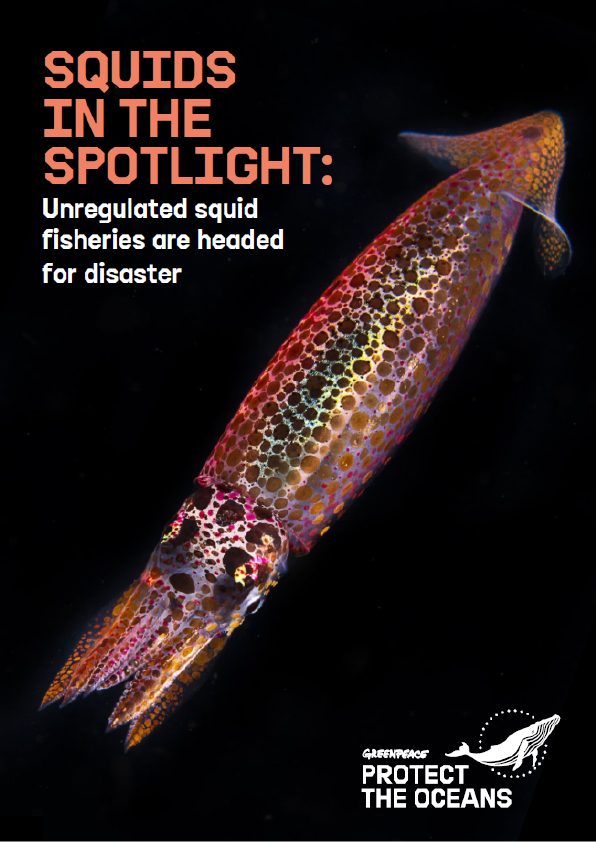

- This fishery is the perfect showcase of how regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) are failing the oceans. Here, ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas) has consistently failed to protect sharks and our oceans from the multiple threats they are facing.

- The solution is a Global Ocean Treaty to fix the broken system of global ocean management. A treaty must be finalized at the UN in August of this year, or it will be impossible to protect 30% of our planet’s oceans by 2030.

HISTORY OF THE FISHERY

The North Atlantic has been fished for swordfish since at least the early 1800s, when harpoons were the primary fishing method.

However, since the introduction of longline gear in the 1960s and the establishment of the ICCAT, the fishery has evolved from a high value, relatively low volume, and often recreational fishery, into one dominated by heavy industry – with Spain responsible for the vast majority of the catch.

The fishery saw a rapid expansion in the 1990s and issues of compliance and overfishing have dogged it ever since. A 1997 study revealed that more than 75% of Spain’s swordfish catch in the North Atlantic was under the regulation size and it frequently exceeded its total allowable catch in the preceding years.

Although the population is now undergoing a slow recovery, with ICCAT taking limited measures to reduce the total allowable catch, and expanding longline fleet has found insufficient swordfish to satisfy commercial interests. Indeed, as early as 1996, the ICCAT Scientific Committee (the SCRS)5 was aware that certain fleets targeting swordfish had “opportunistically” changed their activities to target sharks, catching mainly blue and shortfin mako sharks to take advantage of “market conditions” and higher catch rates.6 This was exacerbated by the EU’s introduction of a ‘fins naturally attached’ policy nearly ten years ago, which requires the full body of sharks to be landed in order to end highly wasteful shark-finning practices.

In 2005, the SCRS disclosed that around 70% of ‘bycatch’ landed by the Spanish surface longline fleet in the Atlantic Ocean (which was supposedly targeting swordfish) was large pelagic sharks. The three most prevalent species in the catch, Swordfish (Xiphias gladius), blue shark, (Prionace glauca), and mako shark (Isurus oxyrhynchus), represented on average about 93% of the total landings in weight. Prionace glauca and Isurus oxyrhynchus are the most prevalent species within the group of large pelagic sharks, representing 86.3% and 10.5% respectively – similar to levels observed in other oceans.

Then, in 2014, the evolution of this fishery was confirmed in an application by Spanish companies for Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification to catch both swordfish and blue sharks. By 2017, the North Atlantic swordfish fishery’s primary catch had shifted to sharks at an estimated ratio of 4:1 (by weight). A few years later, a 2019 Greenpeace investigation observed Spanish longliners north of the Azores hauling in eight times as many sharks as swordfish.

However, this shift of the fishery from swordfish to sharks has not been matched in the policy arena, where regulations to manage shark fishing have long lagged behind the industry’s exploitation of the species. It was only in 2019 that a quota for blue sharks was finally set for the Northern and Southern Atlantic Ocean – the first of its kind set in this ocean by an RFMO. Despite the relative lack of regulation compared to tuna or swordfish, and the high potential for lack of compliance with what little regulation exists, the demand for shark products has never been higher. As such, we face a rapidly escalating situation that the relevant management bodies are doing little to address.

The question that arises is why? Why, in the face of a relatively long yet insufficient story of cooperation with other instruments and agreements, are some States continuing to argue against a progressive Global Oceans Treaty that could restore the marine environment and vital populations of sharks?