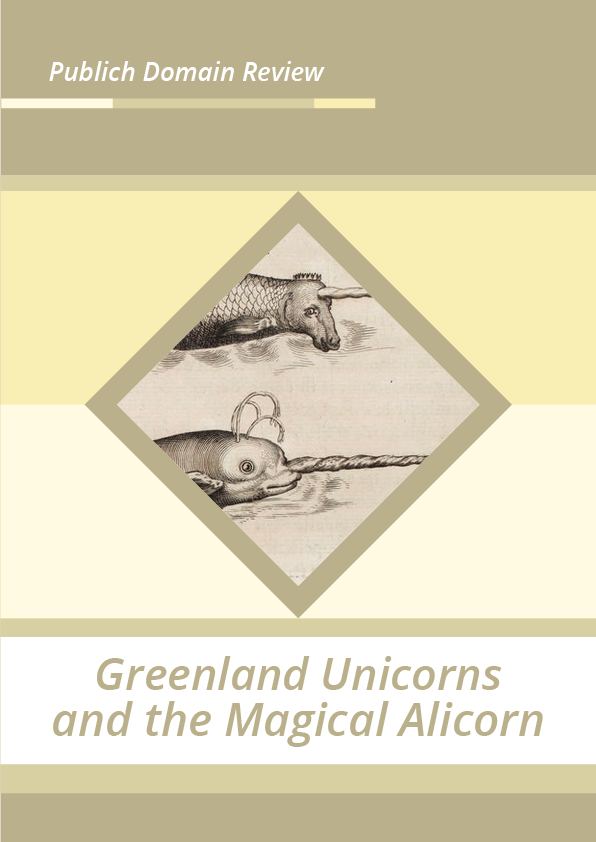

When the existence of unicorns, and the curative powers of the horns ascribed to them, began to be questioned, one Danish physician pushed back through curious means — by reframing the unicorn as an aquatic creature of the northern seas. Natalie Lawrence on a fascinating convergence of established folklore, nascent science, and pharmaceutical economy.

Unicorns seem to be everywhere these days. It’s virtually impossible to walk down a high street or go into a gift shop without coming face to face with one of these rainbow-spangled creatures in some form or other. They have become a fashionable cultural icon of fantasy, escapism, and (somewhat paradoxically) individuality — a fact exploited to the full by manufacturers and marketing experts. All the same, most people today are well aware unicorns don’t exist.

In the seventeenth century, the existence of the unicorn was a serious matter of contention. What was at stake was far more than the fantasy worlds of tweenage girls: this fantastical beast was the basis for a whole body of scholarly literature and a lucrative international market in pharmaceuticals (both recreational and medicinal). As Professor Bernd Roling shows in his 2014 essay “Der wal als schauobjekt”, one family in particular were responsible for the demise of the unicorn’s long-standing market value in Europe. Caspar Bartholin, his brother-in-law Ole Worm, and his son Thomas Bartholin were a trio of Scandinavian scholars and physicians who scrutinized the unicorn and its purported medicinal powers. Their work culminated in the publication of Thomas Bartholin’s De Unicornu Observationes Novae (New observations about the unicorn) in 1645 (second edition in 1678). Quite counter to Thomas’ intentions, this book precipitated the shunting of the unicorn from credible reality into myth.

De Unicornu Observationes Novae dealt with “unicorns” in the broadest sense, examining all animals with a single horn. Thomas cast his net wide because he was attempting to undertake a very important task: to prove that simply having a single horn didn’t qualify something as a unicorn. He wanted to show that “real” unicorns did exist and that their horns were a key ingredient for many potent medicines. In doing so, though, he had to replace the traditional European image of unicorns as terrestrial antelopes or horses that inhabited exotic Eastern wilds by demonstrating that unicorns were actually aquatic creatures from the North.

Natalie Lawrence is a freelance writer and researcher, currently writing a book on monsters throughout history. She received her PhD in history of science from the University of Cambridge. Her thesis was “Monstrous Assembly: Constructing Exotic Animals in Early Modern Europe”, and examined the making and use of wonderful novel beasts, including the angelic birds of paradise from the spice-filled east, the pangolin and armadillo from both Indies, the walrus from the frozen Arctic and the bulbous dodo of Mauritius.