Anomalies

Anomalies refer to anything outside the ordinary, for example conjoined twins or missing limbs. Even though we commonly think of developmental anomalies as inherently “bad”, they are not fundamentally so. For example, the average height of an NBA player is 6’7″. Although this is anomalous (only 0.045% or one in 2200 American men are this tall or taller), it is not considered at all detrimental to be this tall. If you are a Developmental Biologist, you relish natural variation as a window into developmental processes. For example, you might find out what an NBA player ate growing up, how tall his parents are, if he grew up in a rural area or the city, and compare these data to the data of an average American man. The differences between the two can help you generate hypotheses regarding the developmental processes leading to tall height.

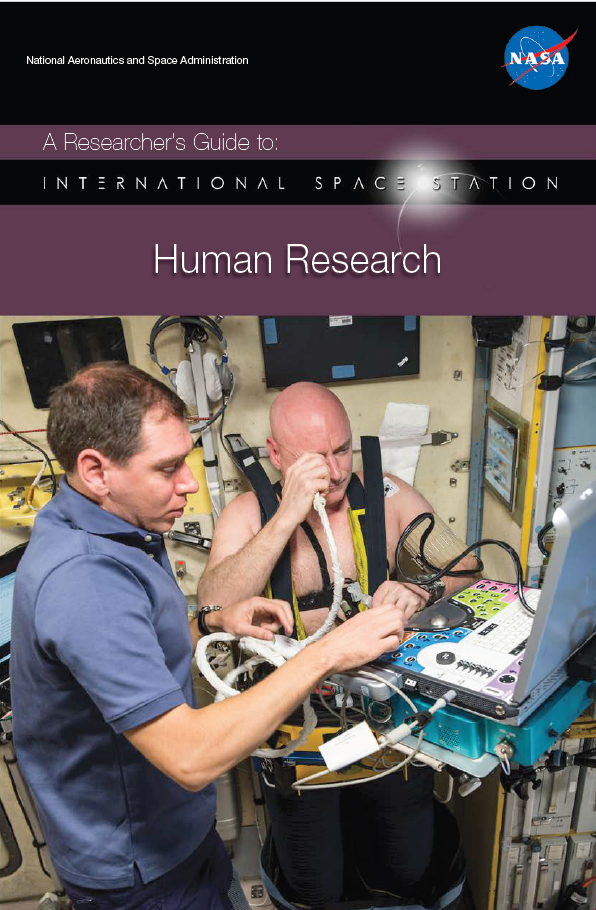

Figure 1: The poster to the left shows an advertisement for a tall man, Franz Winklemeier, who toured Europe in the 1880s. alt Image from Wellcome Images CC BY 4.0

At a deeper level we also notice something more fundamentally interesting about a very tall (or very short) person. Most people who are quite tall or quite short (say a 4’7″ woman), have bodily proportions that are nearly the same as someone of average height. For example, their arms aren’t placed too low, their neck isn’t particularly long, their legs reach all the way to the ground. In short, their body has been “scaled” to a larger or smaller size. This leads us to think that perhaps development itself is scalable. Surely the blueprints for building a very short person are not so different from the blueprints for building a very tall person. Our current understanding is that signals from growing body parts signal to each other to accomplish this task. The same signals build a short or tall body, but a tall body might undergo more cell division or longer periods of growth than a short body.

Cell division is an important developmental process. What are some other developmental processes?

Classical Developmental Biology relies on mutations (gene based) and teratogenic (environment based) anomalies to dissect processes like this. Not only can we compare “normal” anomalies like heights that fall two standard deviations from the average, but we can also look at more rare anomalies like conjoined twin tadpoles or a cyclopic (one eyed) mouse. Both of these anomalies have the bonus of being able to be created in the lab. In fact, we can create them using either genetics, or environmental insult (a teratogen).

The Evolution of Development or the Development of Evolution?

In a very real way, the fields of Development and Evolution cannot be truly separated. When we study Developmental Biology we are mostly looking at a fine-tuned mechanical and genetic process that has been selected on for eons. Not only can evolution select on the final product – a working, fertile adult – but it also can act at each developmental stage. It is easy to imagine how evolution acts through natural selection on adults, but how can it act on development itself?