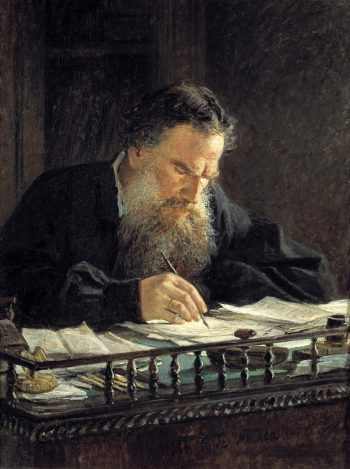

Stefan Zweig, whose works passed into the public domain this year in many countries around the world, was one of the most famous writers of the 1920s and 30s. Will Stone explores the importance of the Austrian’s early friendship with the oft overlooked Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren.

‘Friendship stands highest on the forehead of humanity…’ Keats

While still at school, Stefan Zweig had tried his hand at translating a number of French and Belgian poets, Verlaine, Mallarmé and Baudelaire, but also another name almost unknown to us today, Emile Verhaeren. Something about the elemental nature and incendiary vision housed in the rugged and unorthodox language of the Flemish born Verhaeren resonated with the youthful Zweig, jarring somehow with the comfortable, ordered cultural advancement of his existence, where the restless wanderings of later life were calmly incubating. Zweig’s own work in these early days seemed about to follow a very different course. As is well known, Zweig came from a privileged Jewish bourgeois background in Vienna, the intellectually buoyant yet self regarding metropolis at the heart of the sprawling Hapsburg kingdom, where the young Zweig was liberally steeped in art, literature and music from an early age. In Vienna, Zweig maintained good relations with his parents after completing his schooling, but immersed himself completely in the Viennese café lifestyle of a writer, a period in which he learned the importance of personal freedom through wide ranging dialogue with diverse artists and literary figures. This formation period was where Zweig’s undying thirst for wider travel and experience of the foreign was seeded. But as the century turned, Zweig was absorbed with his coming of age literary achievement, the publication of a first collection of poems at the tender age of twenty-one.

Silberne Saiten (Silver Strings) was well-received and unlike most first efforts by a newcomer, found favour amongst Vienna’s critics, even one Rainer Maria Rilke responded gratefully to his copy, by sending Zweig a dedicated book. Yet these ‘smooth, able verses’ yielding to accustomed versification were as Zweig soon realized too much of a borrowing, a reconstituted product of a time and place, or more aptly of a time that had now passed, but was still hanging on in the Viennese literary salons, like incense in a nave, a stale fragrance which the gathering wind of modernity was soon to brutally disperse. Although this book brought Zweig’s name into the limelight for the first time, it served as a temporary shackle, which he sought to remove at the earliest opportunity. When Zweig left for Berlin and university in 1902, he left Vienna as the most prominent of the younger writers, an overnight success, but in essence he had not yet even begun.

In Berlin, apart from his studies and bohemian indulgences, Zweig sought a more expansive freedom in literary terms, and caught the bug of translation. He began to explore further afield, even translating poets such as Keats and Yeats and producing with other translators a collection of Verlaine’s poetry to which he added a critically acclaimed introduction. But all the time he was moving closer to Belgium, drawn by the rich crop of its home grown artists and writers who seemed to integrate their works in fresh and creatively productive ways. So in the summer break of 1902, long anticipating a visit to the ‘little land between the languages’, Zweig made his move.

Verhaeren had come onto his radar while still at school, when he found a copy of the poet’s first Rubenesque collection Les Flamandes (1883) and instinctively attempted a clutch of translations. He had even written to Verhaeren in 1898 to secure permission to publish them in a journal. Now, he was determined to meet the man himself, though it was the novelist Camille Lemmonier, to whom Zweig had recently dedicated an essay, whom he first located in Brussels. Zweig had sent a postcard in rather shaky French to Verhaeren suggesting a meeting, but it was unclear when Zweig arrived in the Belgian capital if this rendezvous would come to pass. On arrival it seemed that Verhaeren was away and Zweig’s hopes were dashed, but by a fateful stroke, Lemmonier then invited him to meet the sculptor Charles van der Stappen, and Verhaeren just so happened to be in the sculptor’s studio sitting for a bust. Zweig’s memories of that first crucial encounter with the older man are pertinent.

For the first time I felt the grasp of his vigorous hand, for the first time met his clear kindly glance. He arrived as he always did, brimming over with enthusiasm and the experiences of the day…It seemed as though he projected his whole being towards you…he knew as yet nothing of me, yet already he was full of gratitude for my inclination, already he offered me his trust just because he heard I was close to his work. In spite of myself, all shyness faded before the stormy onset of his being. I felt myself free as never before, in the face of this unknown, open man. His gaze, strong, steely and clear, unlocked the heart.

The vital importance of Zweig’s meeting with Verhaeren in relation to his ensuing career as a writer, emissary of humanism and key proponent for the higher ideal of a Europe of cultural unity, cannot be underestimated. The contrast between Verhaeren’s openness, curiosity, vitality, not to mention the explicit visionary credentials he held, and the self conscious dandified Viennese poetry circles Zweig had moved within was extreme. It was if Zweig himself had suddenly been released from a reserve of pampered elites into the rawness and unpredictability of the wild and could finally breathe real air, taste real food and appreciate the creative potential of risk and unpredictability. In Verhaeren’s verses he saw bold new vistas opening up which seemed to strike a necessary chord with the rapidly transforming epoch, as the fabled ‘golden age of security’, guarded by the Hapsburg realm unceremoniously gave way to something far more restless, ominous and uncertain.