Propaganda and Prophecy

Said to be spawn of the devil himself and possessed with great powers of prophetic insight, Mother Shipton was Yorkshire’s answer to Nostradamus. Ed Simon looks into how, regardless of whether this prophetess witch actually existed or not, the legend of Mother Shipton has wielded great power for centuries — from the turmoil of Tudor courts, through the frictions of civil war, to the spectre of Victorian apocalypse.

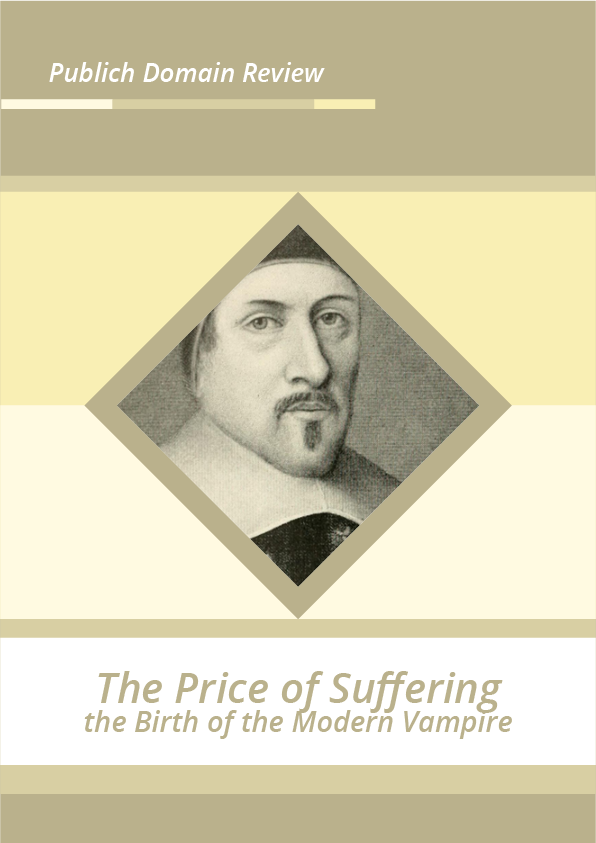

In 1488 during the reign of Henry VII, one year after the Dominican Heinrich Kramer wrote his notorious witch-finding manual Malleus Maleficarum, an adolescent girl named Agatha Soothtell gave birth in a cave among the dales and moors of Yorkshire to her daughter Ursula, supposedly conceived by the Devil himself. Ironically it was there in “God’s Own Country” that young Agatha would raise her demonic charge, both of them forced to live in the cave where Ursula was born. The site that would be visited by pilgrims for centuries afterwards, making it arguably England’s first tourist attraction, was known as much for the strange calcifying waters of its subterranean whirlpool as for its medieval Satanic nativity.

Most sources claimed that Ursula died during the rule of Elizabeth I in 1561, but with eight decades separating her supposed death and the first appearance of her name in print, it’s fair to assume a degree of invention in her biography. Despite her legendary ugliness (Ursula’s seventeenth-century biographer described her as “a thing so strange in an infant, that no age can parallel”), at the age of twenty-four she married a carpenter named Toby Shipton, and it is to posterity that she would come to be known as “Mother Shipton”. A less appropriate surname, because as “Smith” and “Taylor” indicate profession, so too did “Soothtell”. Mother Shipton would become the most famed of soothe tellers in English history, renowned for her prophecies and used as a symbolic familiar in the art of divination for generations, the very constructed personage of the seer, a work of poetry unto herself. As scholar Darren Oldridge writes, “Unlike other ‘ancient prophets’ who were known by their words alone, Shipton emerged as a personality in her own right”.

It is likely at least some of Mother Shipton’s predictions were invented long after she lived, her prophetic couplets revised and edited to conform to later events, whether Cardinal Wolsey’s death, the Great Fire of London, or the Crimean War. Details of her biography, her writing, and her very countenance are uncertain. The prophetess herself may have been a later invention. Yet Mother Shipton, England’s Nostradamus, the sixteenth-century Sibyl, the Yorkshire prophetess, the Knaresborough witch whose crooked face has stared out from prints hanging on occultist’s walls and in the names of country pubs since the initial printing of her predictions in 1641, should serve as a potent point of reflection for what exactly we talk about when we talk about prophecies.

Ed Simon is a staff writer for The Millions, which the New York Times has called the “indispensable literary site”. A specialist in early modern and early American literature, he holds a PhD in English from Lehigh University, and his most recent book is Printed in Utopia: The Renaissance’s Radicalism (Zero Books, 2020).