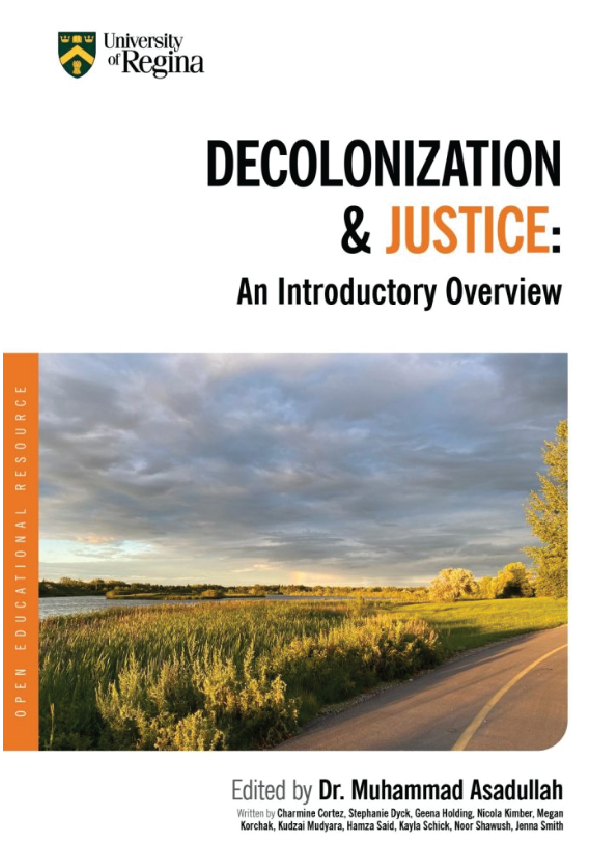

‘Decolonization and Justice: An Introductory Overview’ emerged from the undergraduate students’ final assignment in JS-419 on Advanced Seminar in Criminal Justice at the University of Regina’s Department of Justice Studies, Canada. This book focused on decolonization of multiple justice-related areas, such as policing, the court system, prison, restorative justice, and the studies of law and criminology. This is quite likely one of the few student-led book projects in Canada covering the range of decolonization topics. Ten student authors explored the concept of decolonization in law, policing, prison, court, mental health, transitional justice and restorative justice. We are grateful to receive funding support from the University of Regina’s OER Publishing Program Small Project Grant, which enabled us to hire a professional copy editor for the book.

The chapters in this book are organized under three major thematic areas. The first of these is Decolonization and Post Colonial Criminologies where the authors explore the theoretical aspects of the knowledge tradition and how indigenous legal traditions play an important role within this tradition.

Noor Shawush, in her chapter “Decolonizing the Land: Revitalizing Indigenous Legal Traditions”, explores the influence of the natural world on the development of Indigenous legal traditions. Her investigations elucidate decolonization by looking at how it has impacted Indigenous laws. In so doing, she brings forth the crucial role language and ceremonies play in this regard. As opposed to the Western legal traditions, there was never any need for the Indigenous legal traditions to be written down. Settler colonialism eroded the practice of many legal traditions and placed Indigenous groups in new lands, forcing them to leave the environment on which their legal traditions, knowledge and language were sourced. This was done by displacing Indigenous peoples from their traditional lands and limiting their access to resources.

In her chapter entitled “Decolonization and Criminology: An Analysis of Knowledge Production”, Charmine Cortez argues that the discipline of criminology in the settler-colonial State has been affected by the current systems of oppression that criminalize certain groups. She also reflects on the powerful ideological ramifications of the current criminological structure and the harm it causes to marginalized communities through the Western Justice System. Therefore, decolonization can occur in a variety of disciplines and settings, such as the Criminal Justice System, which consists of the police, courts, and corrections. She contends that these institutions harbour settler-colonial sentiment and ideologies through structures that generate cycles of harm by perpetuating inequalities amongst Indigenous people and other marginalized communities. Mainstream criminology maintains the relations of internalized colonialism and the political economy of criminalization by avoiding the socio-historical critique.

Geena Holding explores the impact of colonialism on court systems and their potential for decolonization in the chapter on “Justice For All: Decolonizing Courts Through Indigenous Justice”. The lack of culturally appropriate sentencing processes and alternatives became clear with the implementation of several landmark developments. For example, in Canada, Gladue reports led to the creation of First Nations Courts (FNCs) and programs that are designed by Indigenous peoples to provide a culturally appropriate alternative form of dispute resolution. The Tsuu T’ina Peacemakers Court was established in 2000 and was the first of its kind in Canada. It integrated the Alberta Provincial Court with the Tsuu T’ina Nation community and justice traditions.

In the second section of the book entitled Emerging Praxes around the Globe, four authors present case studies of innovative and emerging practices of post-colonial criminologies both in post-conflict areas and advanced democracies like Canada.