A mysterious kidney disease is striking down labourers across the world and climate change is making it worse. Jane Palmer meets the doctors who are trying to understand it and stop it.

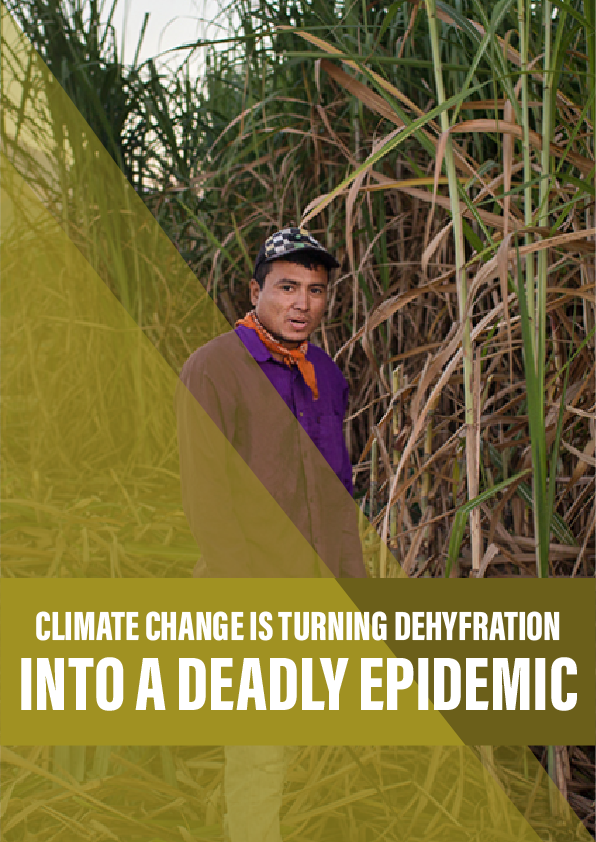

By 10am in the sugarcane fields outside the town of Tierra Blanca in El Salvador, the mercury is already pushing 31°C. The workers arrived at dawn: men and women, young and old, wearing thick jeans, long-sleeved shirts and face scarves to prevent being scorched by the sun’s rays. They are moving quickly between rows of cane, bending, reaching, clipping and trimming in preparation for harvesting the crop in the weeks to come. In the scant shade, old Pepsi and Fanta bottles full of water swing from tree branches, untouched. Gulping only the thick air, the workers won’t stop until noon, when their shift is over.

Among them is 25-year-old Jesús Linares. His dream, he explains in English, was to be a language teacher, but like many Salvadoran children he went to work to help support his parents and siblings. Aged eight, he learned to hide in the towering canes whenever the police sought out underage workers; since then, he’s tended sugarcane from dawn to noon and then pigs until dusk. In the evenings, he tries to listen to English audio programmes or read a language book, but for the last year he’s been too tired to concentrate. So tired, in fact, that a few months ago he visited the Tierra Blanca clinic. Blood tests revealed that Linares was in the early stages of chronic kidney disease.

It’s a familiar story here in the Bajo Lempa region, where recent studies suggest that up to 25 per cent of its nearly 20,000 inhabitants have chronic kidney disease. Across El Salvador, kidney failure is the leading cause of hospital deaths in adults. But while chronic kidney disease is most commonly caused by hypertension and diabetes, two-thirds of patients in Bajo Lempa don’t have either of those conditions, and the cause of their illness remains uncertain.

Scientists have identified certain key themes. The majority of people with the unexplained disease are men, and it strikes predominantly in hot, humid regions where people are engaged in strenuous outdoor labour: farming, fishing or construction work. Dehydration, which seems an obvious factor, causes acute kidney disease that is easily reversed by drinking water, rather than this chronic form. This has left two burning questions: what causes this new form of kidney disease, and will it be likely to spread as the world gets warmer?

Meanwhile, in El Salvador over the last two decades, more and more patients have arrived at clinics and hospitals, often taxing them to their limit. Many people, unable to get treatment, simply return to their homes to die.

“This is really a silent massacre,” says Ramón García-Trabanino, a Salvadoran kidney specialist.

- A recent article by García-Trabanino, Johnson and colleagues sets out the link between climate change and the new form of chronic kidney disease.

- The Nefrolempa study published results of its investigation into chronic kidney disease in the Bajo Lempa region in 2011. (In Spanish, with an English abstract.)

- The Emergency Social Fund for Health (FSES) published results of its 10-year research in the same region in 2016. (In Spanish, with an English abstract.)