In 2009, a team of Oxfam researchers traveled around Bolivia, collecting information about the country’s vulnerability to climate change and interviewing experts, government officials and NGOs, and most importantly, poor women and men, mostly from Indigenous communities, about their experiences of climate change and their efforts to adapt to it. Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a country located in western-central South America. The seat of government and executive capital is La Paz, while the constitutional capital is Sucre.

In the report that followed, Oxfam stressed that Bolivia was particularly vulnerable to climate change due to widespread poverty, its variety of ecosystems, weather extremes, melting glaciers, and high deforestation rates. It found that many producers and local farmers were already witnessing a changing climate, in terms of unpredictable rainfall, more disasters stemming from extreme weather events, and higher temperatures, with negative impacts on their livelihoods. Women were often the hardest hit as they were usually left to tend families and small-scale farms, and had fewer alternative livelihoods when crops were lost.

The report outlined five main impacts that Bolivia could expect as a result of climate change: less food security; glacial retreat affecting water availability; more frequent and more intense ‘natural’ disasters; an increase in mosquito-borne diseases; and more forest fires.

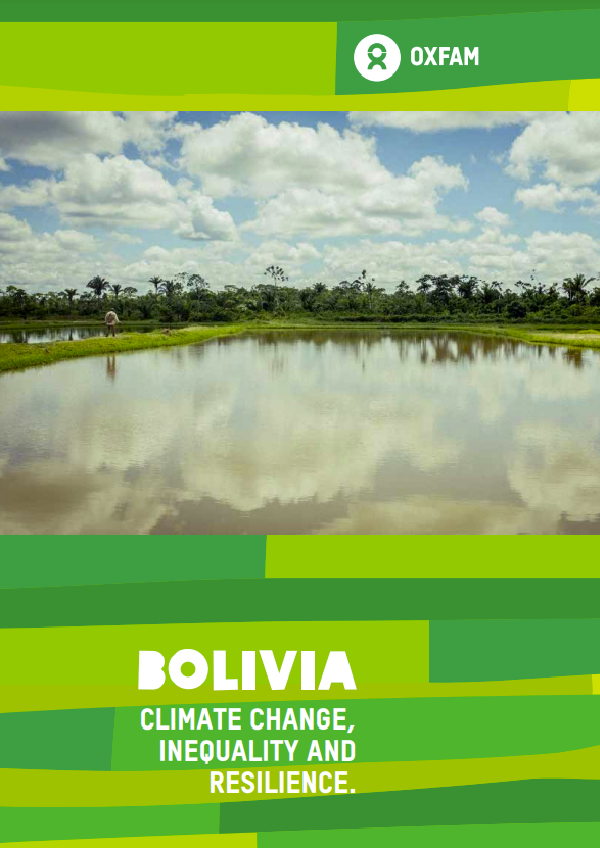

A little over ten years later, a similar team of researchers traveled to different regions of Bolivia, in part to see what had changed and to delve deeper into some aspects that had not been covered previously. We revisited the small village of Khapi in the municipality of Palca, tucked under Mount Illimani in the department of La Paz, where villagers were feeling the effects of water insecurity partly because of receding glaciers.

The team also spent time examining the aftermath of the devastating forest fires, the worst in Bolivia’s recent history, which affected the Chiquitania region in the east of the country in the second half of 2019. Here climate change played a role as a ‘stress multiplier’, creating weather conditions (less water availability and higher temperatures), which made the fires worse.

Finally, the researchers visited Bolivia’s remotest department of Pando in the Northern Amazon, where several communities are pursuing a variety of alternatives to burning down or clearing forests. Such stories are an inspiring antidote to the general ‘doom and gloom’ narratives around climate change.

Many of the testimonies collected on this visit were familiar from the first visit in 2009. In particular, the repeated experiences of hotter temperatures, unpredictable or shorter periods of rainfall, sudden downpours, and more droughts were a common refrain in all three regions we visited.

Since 2009, Oxfam and its partners have continued to document the ways climate change has a much greater impact on women (particularly because they are usually in charge of agricultural production), to give voice to their experiences of resisting hydroelectric schemes, oil companies, and road building in different parts of the country, and to assess progress in women’s participation and decision-making powers in social organizations and other public bodies.