The story of Pacific and Australian exploration by Europeans is a story of interpersonal and cross-cultural encounters. As European technology changed, and European explorers set out to discover the world, they found they were not the first people to discover the islands of the Pacific or the Australian continent. The places the explorers came to already had a human past, and the explorers’ own histories meant they arrived with pre-conceived ideas of what they would find. This meeting of cultures has left fascinating records, in the form of the journals and maps created by European explorers. The European discovery of an already discovered region is a curious history of encounter, misconception, conflict, adjustment, and engagement.

While explorers might seem readily identifiable, the terms ‘explorer’ and ‘exploration’ are difficult to define. Since the 1980s, historians have interrogated the ways in which the terms are applied, and their analyses recognise the links between exploration, empire building, publication and self-promotion, collection of samples and specimens, and ties to significant institutions within the explorers’ home countries. The situation is further complicated by the term only gaining its current sense in the Victorian period, and by the blurriness of the distinction between exploration and travel. Explorers tended to be leaders of their expeditions, and to publish accounts of their travels, but these elements were not universal. However, all explorers were connected in some way to their home communities, either by being forerunners of settlement or colonisation, or representatives of the state, or connected to significant institutions, or authors of widely read books. Travellers might have similar connections, but explorers could distinguish themselves by deliberately facing danger, or at least undergoing physical suffering during their expeditions.

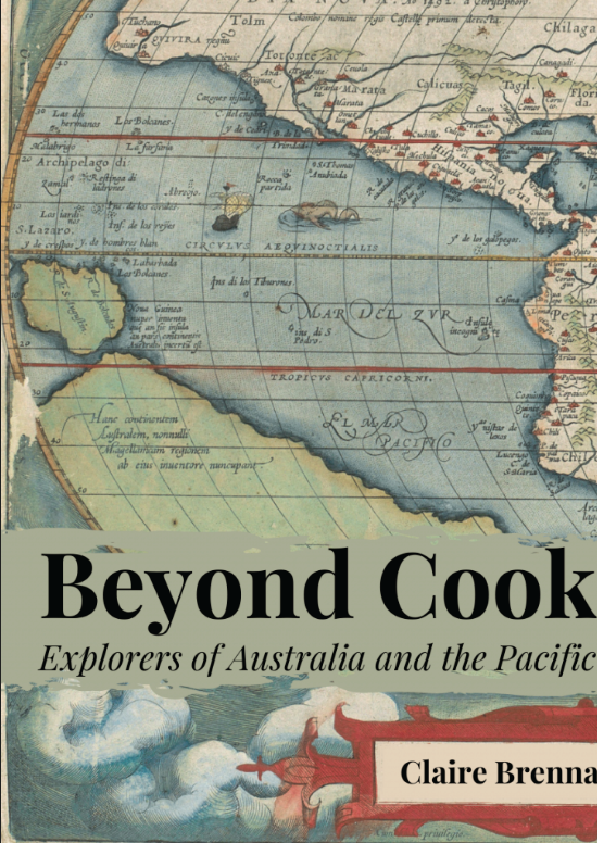

Most explorers cemented their status by publishing accounts of their expeditions, leaving us intriguing documents. When we read the journals written by the explorers and when we examine the maps constructed from the information they collected on their travels, we peer at the past through distorted lenses. We can glimpse Indigenous societies and individuals during the period of contact (and then during the period of growing familiarity with Europeans), and we can also catch glimpses of the documents’ authors. European records of island societies can offer windows on Pacific pasts, offering observers in the present a view of Pasifika ancestors and their achievements. The records of exploration also offer us views of the explorers’ own societies, and their expectations of the world based on their previous experiences, hopes, and fears. The journals and maps are both windows and mirrors: they contain observations of the world beyond Europe, and they reflect European preconceptions and European systems of thought.

The experiences, perceptions, and records created by European explorers during their voyages within the Pacific linked Europe and the Pacific together in many ways. The Pacific became an element of European cultural history as Europeans used their Pacific experiences to think with, and to examine their own societies. The Pacific found a place in the history of science as it became a space where significant observations were made. And the Pacific and Australia became places where Europeans established empires and settler colonies. European explorers self-consciously identified resources and potential sites for colonies, and as a result the peoples of the Pacific and the Australian continent experienced histories of colonisation.