In 1884 Edwin Abbott Abbott published Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, perhaps the first ever book that could be described as “mathematical fiction”. Ian Stewart, author of Flatterland and The Annotated Flatland, introduces the strange tale of the geometric adventures of A. Square.

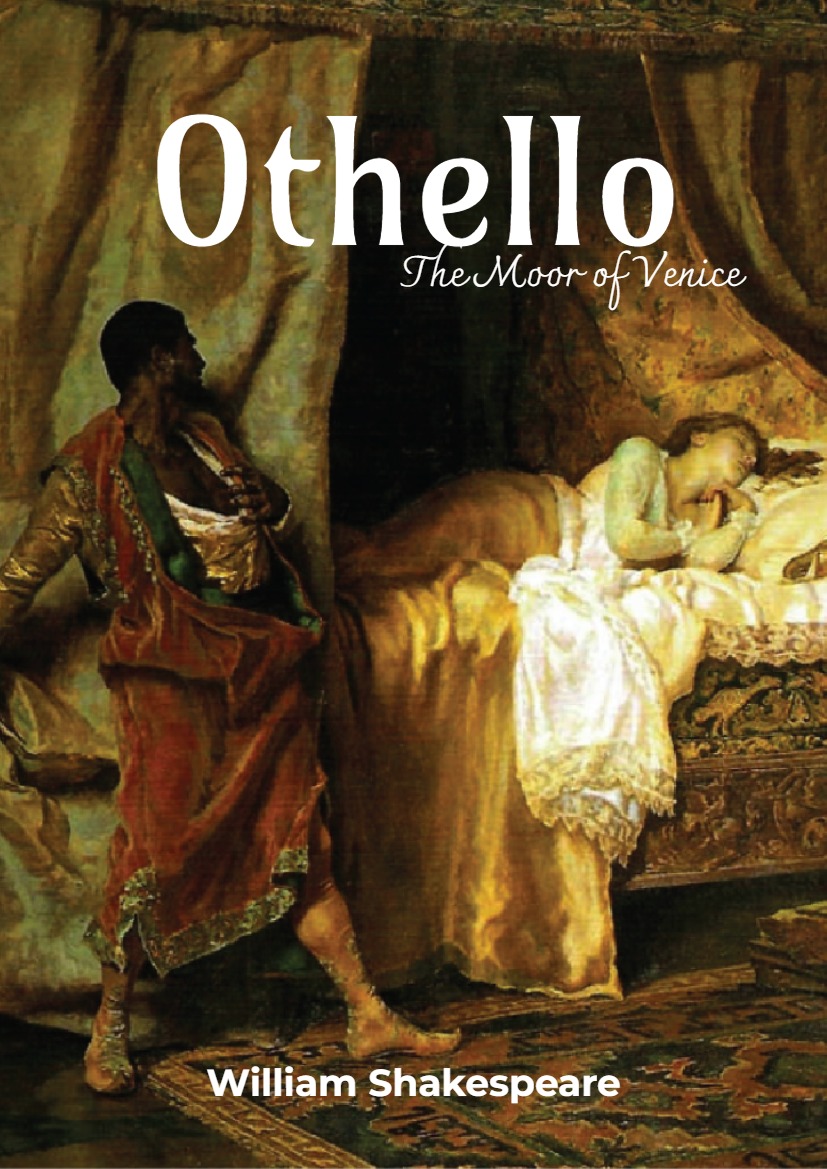

Edwin Abbott Abbott, who became Headmaster of the City of London School at the early age of 26, was renowned as a teacher, writer, theologian, Shakespearean scholar, and classicist. He was a religious reformer, a tireless educator, and an advocate of social democracy and improved education for women. Yet his main claim to fame today is none of these: a strange little book, the first and almost the only one of its genre: mathematical fantasy. Abbott called it Flatland, and published it in 1884 under the pseudonym A. Square.

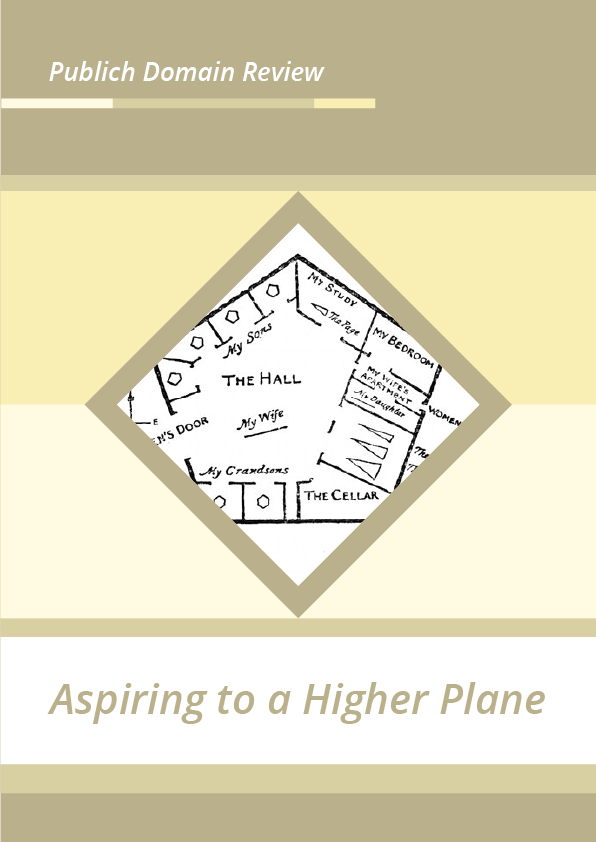

On the surface — and the setting, the imaginary world of Flatland, is a surface, an infinite Euclidean plane — the book is a straightforward narrative about geometrically shaped beings that live in a two-dimensional world. A. Square, an ordinary sort of chap, undergoes a mystical experience: a visitation by the mysterious Sphere from the Third Dimension, who carries him to new worlds and new geometries. Inspired by evangelical zeal, he strives to convince his fellow citizens that the world is not limited to the two dimensions accessible to their senses, falls foul of the religious authorities, and ends up in jail.