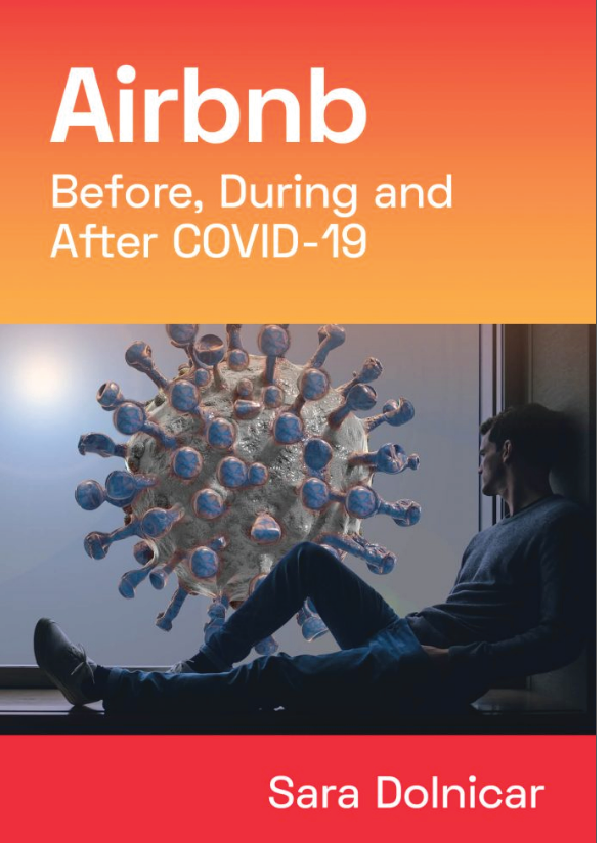

Is Airbnb part of the sharing economy?

The ability to bring together buyers and sellers via online platforms has fundamentally reshaped many industries, including the tourist accommodation sector. Facilitators of well-developed online platforms is safe, and offer a range of benefits compared to using traditional intermediaries. These benefits include lower commission rates, a more balanced power relationship between buyer and seller, higher flexibility for sellers, and the potential to find a better match between accommodation features and traveller needs because of the substantial variability of spaces listed on such online platforms (Dolnicar, 2018). Online platforms enabled ordinary people to not only buy, but also sell products and services. The term sharing economy was increasingly used to describe what was essentially a rise in the popularity of platform businesses. Platform businesses connect buyers and sellers without engaging in direct interaction when buyers and sellers make a transaction. The platform enables sellers to present their product or service, making it visible to buyers. But the terms of the transaction and the decision to go ahead with a specific transaction are up to the buyer and seller (Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2018). Platform businesses existed long before Airbnb, ranging from “dating clubs (men and women), to video game consoles (game developers and users), to payment cards (cardholders and merchants), to operating system software (application developers and users)” (Evans, 2003: 1).

The key to their success is attracting and maintaining a substantial pool of different types of customers (Evans, 2003), in the case of Airbnb; people who have available space they can rent out to others for short periods of time (hosts), and people who are in need of short-term accommodation (guests). Sharing is not associated with platform businesses as such. This is not surprising. Definitions of sharing include to “have or use something at the same time as someone else” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2020), and to “partake of, use, experience, occupy, or enjoy with others” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2020). Neither of these descriptions reflect the transactions that take place on Airbnb and similar accommodation platforms. Even the most aligned of definitions (to “allow someone to use or enjoy something that one possesses”, The Free Dictionary, 2020) implicitly assumes that the person who possesses the item being shared does so without payment. Allowing guests to use space without paying is not typically the nature of transactions taking place via most platform businesses.

Some exceptions exist. Couchsurfing.com, for example, is an online platform that facilitates genuine space sharing without a fee. Reinhold and Dolnicar (2018) discuss in detail the sharing-exchange continuum proposed by Habibi and colleagues (2016), concluding that – while different platforms populate different positions along this continuum – Airbnb lacks a number of key features associated with sharing, including the non-reciprocal nature of sharing, a joint sense of ownership, the presence of both sharer and recipient, no calculation of value, money not being the motivation for the sharing, and the formation of social connections that live beyond one transaction. The latter can develop on Airbnb, and many interactions on Airbnb do imply at least a minimum social connection between sharing partners. In the detailed paperwork filed for its initial public offering, Airbnb described itself as a global platform (Airbnb, 2020a) and as an enablement platform (Airbnb, 2020a). It refers to hosts sharing access to their homes, talents and passions in the form of listings and experiences. However, there is not a single mention of the sharing economy.