Despite the recent spate of economic growth, Africa remains afflicted by entrenched poverty and alarmingly high and rising inequality. The gap between rich and poor is greater than in any other region of the world apart from Latin America, and in many African countries this gap continues to grow. In this context, the prospects of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and Agenda 2063 are severely diminished.

This paper uses the Reducing Inequality Index (CRI) developed by Oxfam and Development Finance to produce a ranking of African countries on their policies to reduce the gap between rich and poor, looking at taxation, social spending and labour rights.

It paints an interesting picture. All countries in Africa are dealing with the same poisonous legacy: very high levels of inequality, a history of colonial expropriation and failed economic policies often imposed on them by the IMF and the World Bank. Yet the steps being taken to overcome this legacy and tackle the gap between rich and poor differ hugely from country to country. The CRI shows that it is possible for African governments to choose a path of more equitable growth.

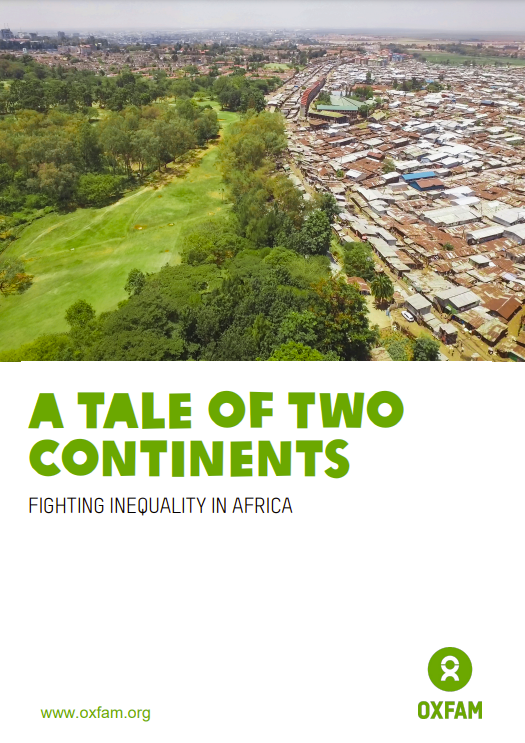

While the richest Africans get ever richer, extreme poverty in the continent is rising. Africa is the second most unequal continent in the world, and home to seven of the most unequal countries. Africa is the world’s second-largest and second-most-populous continent, after Asia in both cases.

The richest 0.0001% own 40% of the wealth of the entire continent. Africa’s three richest billionaire men have more wealth than the bottom 50% of the population of Africa, approximately 650 million people. Meanwhile, Africa is rapidly becoming the epicentre of global extreme poverty. While massive reductions in the numbers living on less than $1.90 a day have been achieved in Asia, these numbers are rising in Africa. The World Bank estimates that 87% of the world’s extreme poor will be in Africa by 2030, if current trends continue.

African women and girls are most likely to be poor. Levels of gender inequality are among the highest in the world, combining with economic inequality to create a suffocating web of exclusion. For example, in Kenya, a boy from a rich family has a one-in-three chance of continuing his studies beyond secondary school. A girl from a poor family has a 1-in250 chance of doing so. Women and girls are also responsible for the bulk of unpaid care and domestic work that contributes to their family, community and the economy. For example, in Malawi, women spend seven times the amount of time on unpaid care and domestic work than men.

Dangerous debts hurt social spending

The economic prospects for Africa are poor. The IMF predicts that 24 of the 45 sub-Saharan African countries, including South Africa and Nigeria, are not likely to see a strong economic recovery. Above all, unsustainable debt has returned to squeeze the populations of Africa. While there have been some exceptional individual cases, there is great risk of a continental crisis that will undermine development for the next decade, while population growth increases.

Reckless lending by European financial markets and Chinese banks, combined with reckless borrowing by a number of African governments, is already severely constricting spending on public services. In Uganda, debt repayments have reached historic highs, and the government has cut spending on education and health by 12%.

Yet the story is not uniformly bad. Many countries in Africa are taking positive steps to tackle inequality. The fact that they are doing so in the face of long odds and huge challenges is a tribute to them and shows up the many countries that are simply failing to do what they should.