Though crossing the Atlantic is most often associated with Spain and Christopher Columbus, the Kingdom of Castile (Spain) and Portugal had been expanding westward for much of the fifteenth century. Instability in the eastern Mediterranean, as well as the fall of the Mongol Empire, encouraged these kingdoms to look elsewhere for a trading route to India. In venturing into the Atlantic, seafarers for these kingdom’s arrived in places previously unknown to them.

Early in the century, for example, Castilian colonizers laid claim to what we know today as the Canary Islands. Portugal, though, was the main driver of Europe’s expansion at this time. Under Henry the Navigator, and then King John II, Portugal expanded its influence to the Madeira and Azores Islands, over 1,500 kilometers from the Portuguese shoreline, as well as along the African coast line, building trading relationships along the way with the hopes of finding a new route to India. Conflict arose between the Castilian and Portuguese crowns over ownership of the Canary Islands.

Both Portugal and Castile were Catholic monarchies. The crowns therefore turned to the Vatican for a ruling, leading to the 1479 Treaty of Alcàçovas, which sided that the Canary Islands belonged to Spain. More generally, though, the treaty outlined Portuguese and Spanish spheres of influence.

The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas extended the diplomacy between the two crowns after Christopher Columbus returned from his first voyage and announced to King John that there were lands to the south and west of the Canary Islands.

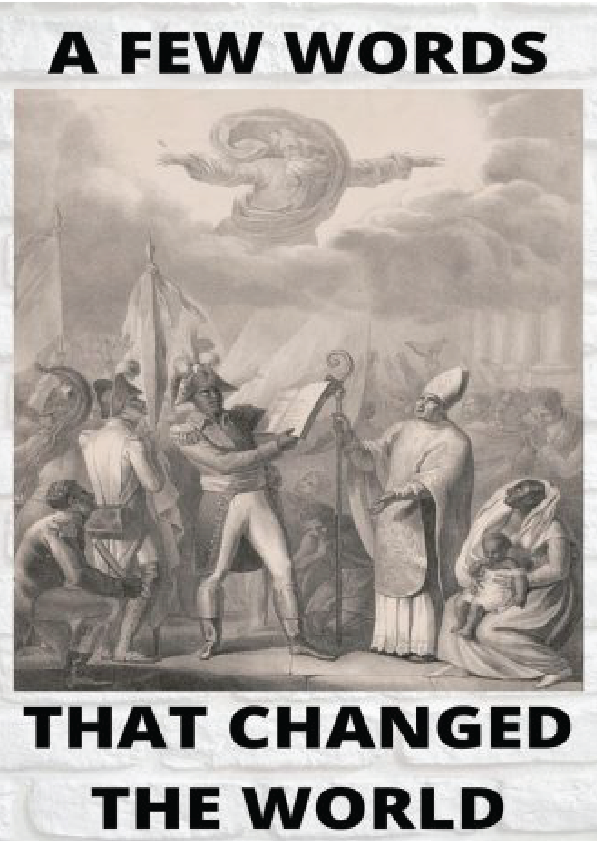

Taking a diplomatic tack, Queen Isabella (Castile) and King Ferdinand (Aragon) sought a new decision from the church. In 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued a Papal Bull Inter caetera that allocated to the Kingdom of Castile all lands found 100 leagues (about 500 km) west of the Azores and Cape Verde Islands. Upset about this Papal decision – especially as it threatened Portuguese efforts to find a new route to India – John II took Isabella and Ferdinand to the bargaining table. The resulting Treaty of Tordesillas moved the line drawn from pole-to-pole a year earlier westward by 270 leagues (about 1,300 km) and acknowledged Portugal’s dominance on the sea. Essentially, the Treaty of Tordesillas granted the lands discovered west of the Papal line to the Kingdom of Castile, while lands to the east belonged to Portugal.

The Treaty of Tordesillas reveals much about how Europeans saw the world at the end of the fifteenth century. It anchors a legal principle known as the Doctrine of Discovery – cemented in North American law in the nineteenth century – whereby European powers, initially through the Catholic Church, granted themselves the right to claim sovereignty over land occupied by non-Christian peoples. As you read through the treaty text, consider the following questions:

- What sense do you get about the state of geographic knowledge in Europe in 1494?

- What was the role of the church in shaping the relationship between John II, Isabella, and Ferdinand (among others)?

- Why was the church so important in mediating this diplomacy?

- What problems do you see arising from this treaty? How do you think they might have been resolved?