The extreme survival tricks of hibernators could help us overcome life-threatening injuries, Frank Swain discovers.

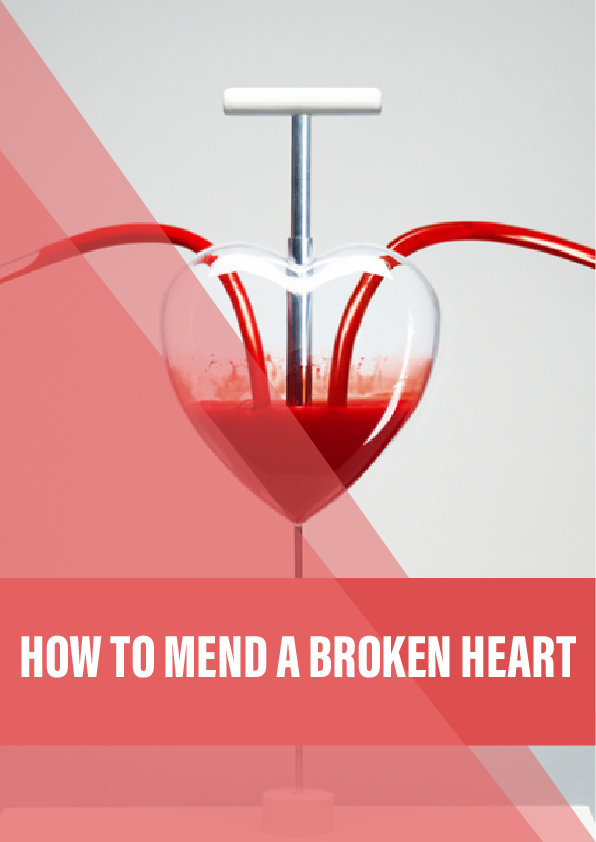

Imagine it: you have been rushed into the emergency room and you are dying. Your injuries are too severe for the surgeons to repair in time. Your blood haemorrhages unseen from ruptured vessels. The loss of that blood is starving your organs of vital nutrients and oxygen. You are entering cardiac arrest.

But this is not the end. A decision is made: tubes are connected, machines whir into life, pumps shuffle back and forth. Ice-cold fluid flows through your veins, chilling them. Eventually, your heart stops beating, your lungs no longer draw breath. Your frigid body remains there, balanced on the knife-edge of life and death, neither fully one nor the other, as if frozen in time.

The surgeons continue their work, clamping, suturing, repairing. Then the pumps stir into life, coursing warm blood back into your body. You will be resuscitated. And, if all goes well, you will live.

Suspended animation, the ability to set a person’s biological processes on hold, has long been a staple of science fiction. Interest in the field blossomed in the 1950s as a direct consequence of the space race. NASA poured money into biological research to see if humans might be placed in a state of artificial preservation. In this state, it was hoped, astronauts could be protected from the dangerous cosmic rays zapping through space. Sleeping your way to the stars also meant carrying far less food, water and oxygen, making the ultimate long-haul flight more practical.

One recipient of that funding was a young James Lovelock. The scientist would dunk hamsters into ice baths until their bodies froze. Once he could no longer detect a heartbeat, he would reanimate them by placing a hot teaspoon against their chest (in later experiments, Lovelock warmed to the space-age theme by building a microwave gun out of spare radio parts to more gently revive his test subjects). These experiments on the flexibility of life would set him on the path to his most famous work, the ‘Gaia hypothesis’ of the world as a living super-organism.

Adventurous as they were, these early experiments did not progress beyond the animal stage, and astronauts were never frozen and revived with hot spoons. The idea of transforming people into inanimate bars of flesh for long-distance space travel remained in the realm of science fiction. NASA’s interest tailed off with the end of the space race, but the seeds planted by Lovelock and his colleagues continued to grow.

Reference:

- More information on the emergency preservation and resuscitation study.

- The UMCG’s Hjalmar Bouma and colleagues look at the induction of torpor by mimicking natural metabolic suppression.

- A curious account of hibernation in Russian peasants, published in the British Medical Journal in 1900.

- James Lovelock’s 1955 report on his experiments with frozen hamsters.

- A good account of the NASA studies can be found in Depressed Metabolism by X J Musacchia and J F Saunders (1969).

- A 1973 NASA report on the role of depressed metabolism in space biology, by Saunders.