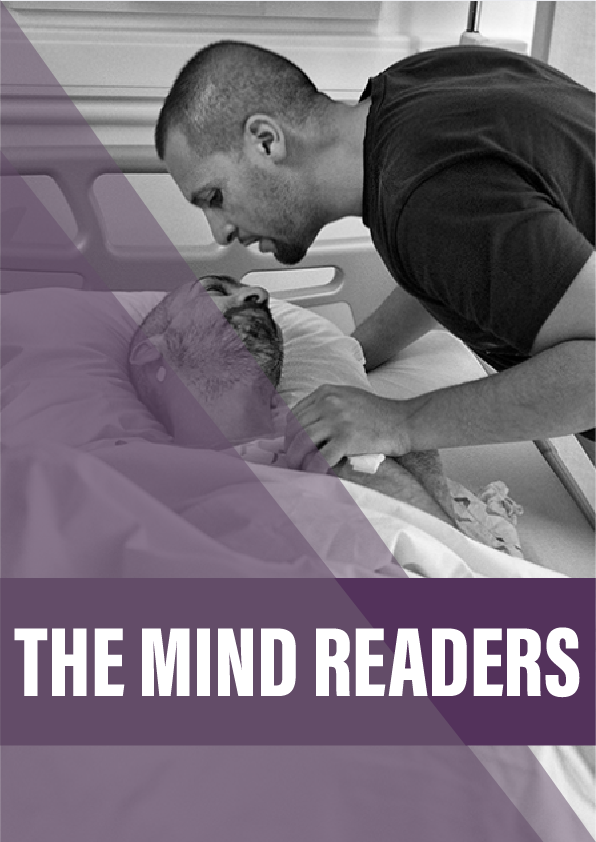

Thousands remain trapped between life and death. Three scientists are working to free them. Roger Highfield reports.

Imagine you wake up, locked inside a box,” says Adrian Owen. “It’s only just big enough to hold your body but sufficiently small that you can’t move.

“It’s a perfect fit, down to every last one of your fingers and toes. It’s a strange box because you can listen to absolutely everything going on around you, yet your voice cannot be heard. In fact, the box fits so tightly around your face and lips that you can’t speak, or make a noise. Although you can see everything going on around the box, the world outside is oblivious to what’s going on inside.

“Inside, there’s plenty of time to think. At first, this feels like a game, even one that is strangely amusing. Then, reality sets in. You’re trapped. You see and hear your family lamenting your fate. Over the years, the carers forget to turn on the TV. You’re too cold. Then you’re too hot. You’re always thirsty. The visits of your friends and family dwindle. Your partner moves on. And there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Owen and I are talking on Skype. I’m sitting in London, UK, and he’s in another London three-and-a-half thousand miles away at the University of Western Ontario, Canada. Owen’s reddish hair and close-cropped beard loom large on my screen as he becomes animated describing the torment of those with no voice: his patients.

People in a ‘vegetative state’ are awake yet unaware. Their eyes can open and sometimes wander. They can smile, grasp another’s hand, cry, groan or grunt. But they are indifferent to a hand clap, unable to see or to understand speech. Their motions are not purposeful but reflexive. They appear to have shed their memories, emotions and intentions, those qualities that make each one of us an individual. Their minds remain firmly shut. Still, when their eyelids flutter open, you are always left wondering if there’s a glimmer of consciousness.

A decade ago, the answer would have been a bleak and emphatic no. Not any longer. Using brain scanners, Owen has found that some may be trapped inside their bodies yet able to think and feel to varying extents. The number of patients with disorders of consciousness has soared in recent decades, ironically, because of the rise and success of intensive care and medical technologies. Doctors have steadily got better at saving patients with catastrophic injuries, though it remains much easier to restart a heart than restore a brain. Today, trapped, damaged and diminished minds inhabit clinics and nursing homes worldwide – in Europe alone the number of new coma cases is estimated to be around 230,000 annually, of which some 30,000 will languish in a persistent vegetative state. They are some of the most tragic and expensive artefacts of modern intensive care.

Reference:

- This article is based on interviews conducted over a decade while the author was the Editor of New Scientist and Science Editor of the Daily Telegraph, on a draft book proposal with Adrian Owen, and on a range of recent interviews with those mentioned in the article and others, notably John Pickard, Tristan Bekinschtein, Athena Demertzi and Lizette Heine. Ben Lheureux helped translate interviews conducted in French.

- Definition of coma from The Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma by Fred Plum and Jerome Posner (1966).

- More on vegetative state from Jennett and Plum in their 1972 Lancet paper.

- Definition and diagnostic criteria for the minimally conscious state.

- A 2012 review of coma and consciousness, reframed by neuroimaging, by Nicholas Schiff and Steven Laureys.

- Papers on what it’s like to have locked-in syndrome and how it makes patients feel.

- An overview of death, unconsciousness and the brain by Laureys.

- A study on how people perceive those in a persistent vegetative state.

- For more information on the mesocircuit, see this pair of papers by Nicholas Schiff.

- The 1998 Lancet paper on Kate’s PET brain scans. Further perspectives on PET in this paper by Laureys’s group.

- The famous 2006 Science paper by Adrian Owen’s group on detecting awareness in the vegetative state. And more on fMRI studies of this in this 2007 paper.

- Owen and Laureys’s study of 54 patients with “disorders of consciousness”.

- Owen and Lorina Naci’s paper on selective auditory attention.

- For more on thalamus stimulation, these three papers are useful.

- A study on Zolpidem and the use of drugs to arouse patients from PVS.

- Schiff’s 2002 paper reporting on PET, MRI and MEG to detect activity in the persistently vegetative brain.

- The study on the ‘dead salmon effect’.

- PET vs MRI: the 2014 paper by Laureys’s group.

- The Schiff group paper questioning the robustness of EEG bedside detection of awareness in the vegetative state.

- Critical perspectives on the brain-scanning techniques in letters to Science from Daniel Greenberg and Parashkev Nachev and Masud Husain and in an editorial in the BMJ by Lynne Turner-Stokes et al.

- The Royal College of Physicians guidelines on prolonged disorders of consciousness for healthcare staff and families.

- Professors Adrian Owen, Steven Laureys and Nicholas Schiff, alongside our author Roger Highfield, took part in a Reddit AMA.

- Adrian Owen and Steven Laureys have both given excellent TEDx talks on this subject, and Nicholas Schiff has given talks to Stony Brook University and to the Internatinoal Neuroethics Society. Owen also did a talk on this for Poptech and you can also see him playing in the band You Jump First.

- More on Kate Bainbridge’s story can be found in two papers that she co-authored. You can see her story in this video.

- For more on Jim’s story, see these news articles in the New York Times and the Telegraph.

- Fergus Walsh’s BBC report on Scott Routley.

- An obituary of Professor Bryan Jennett in the Independent, and one of Fred Plum in Archives of Neurology.