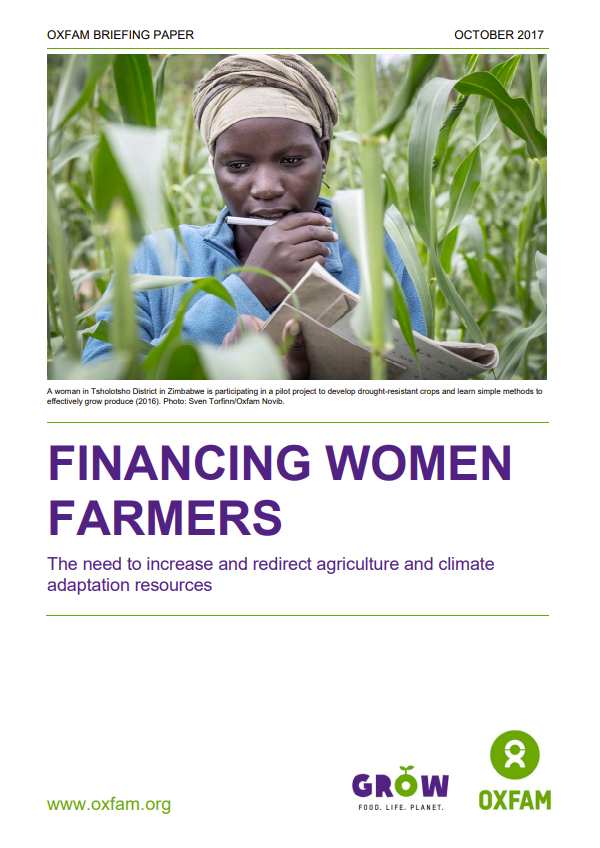

Oxfam analysis finds that governments and donors are failing to provide women farmers with relevant and adequate support for farming and adapting to climate change.

Oxfam conducted research on government and donor investments in Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Tanzania. It found that funding in these countries is significantly lower than commitments that have been made, and there is little evidence of resources and technical assistance reaching women farmers.

Resources are being diverted to priorities other than smallholder farmers, and for the most part, governments lack the capacity to deliver funding to them. A smallholding or smallholder is a small farm operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Definitions vary widely for what constitutes a smallholder or small-scale farm, including factors such as size, food production technique or technology, involvement of family in labor, and economic impact. Smallholdings are usually farms supporting a single family with a mixture of cash crops and subsistence farming. This paper presents the findings along with recommendations for governments.

Oxfam analysis finds that governments and donors are failing to provide women farmers with relevant and adequate support for farming and adapting to climate change. Oxfam conducted research on government and donor investments in Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines and Tanzania.1 Funding in these countries is significantly lower than commitments that have been made, and there is little evidence of resources and technical assistance reaching women farmers. Resources are being diverted to priorities other than smallholder farmers, and for the most part governments lack the capacity to deliver funding to them.

Highlights from the findings include:

• Data analysis confirms there is no evidence of money reaching women farmers, as all of the reviewed countries are failing to gather gender-specific data.

• Only Ethiopia has reached the Maputo target of spending 10 percent of its national budget on agriculture, although this target was already met in 2003 at the time of the Maputo Declaration.

• Ghana invested almost half of its international climate change adaptation funding to support agriculture in 2014, while the women’s ministry received on average 0.1 percent of the government’s climate change budget in 2010–15.

• Nigeria had the lowest share of spending on agriculture and rural development (4.9 percent) as part of international aid in 2007–15.

• Of 3,000 farmers surveyed in Tanzania, about 80 percent reported not receiving extension services.

• In the Philippines, the public works department, which is responsible for infrastructure development, received 88 percent of climate adaptation funding in 2017, while agriculture received just 6 percent.

• In Pakistan in 2014, almost 99 percent of the funding for climate change adaptation was given in the form of loans, with grants amounting to only $3.4m.

Women farmers play a central role in reversing poverty and food insecurity, and building resilience to climate change. About 80 percent of the world’s food is produced by family farms, and small-scale farming is the dominant livelihood in most developing countries.2 Women farmers make up on average 43 percent of this agricultural labour in developing countries, but are the majority in some countries.3 However, they produce 20–30 percent less than men farmers because they often face barriers to accessing farm inputs, markets, technical assistance, extension services and finances. Equalizing this gap could boost agricultural output and decrease global undernourishment by up to 17 percent.