Globally, the gap between the richest and poorest has reached extreme levels and is growing rapidly. The richest 1% in the world now have more wealth than the rest of humanity, and in 2017 they received 82% of the global increase in wealth. In the same year, the poorest half of the world’s population saw no increase in their wealth at all.

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the number of money people is paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the number of wealthy people owns). Besides economic inequality between countries or states, there are important types of economic inequality between different groups of people.

There is a broad consensus, based on a growing body of evidence, that extreme inequality hinders economic growth1 and poverty reduction. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has estimated that growth could have lifted 240 million more people out of extreme poverty in Southeast Asia between 1990 and 2010 if growth had not been accompanied by growing economic inequality. It has also been estimated that tackling gender inequality could add $12 trillion to the global economy by 2025.3 Extreme inequality also corrupts politics, giving the richest and most powerful undue influence over policy-making, so they can skew it in their own interests.

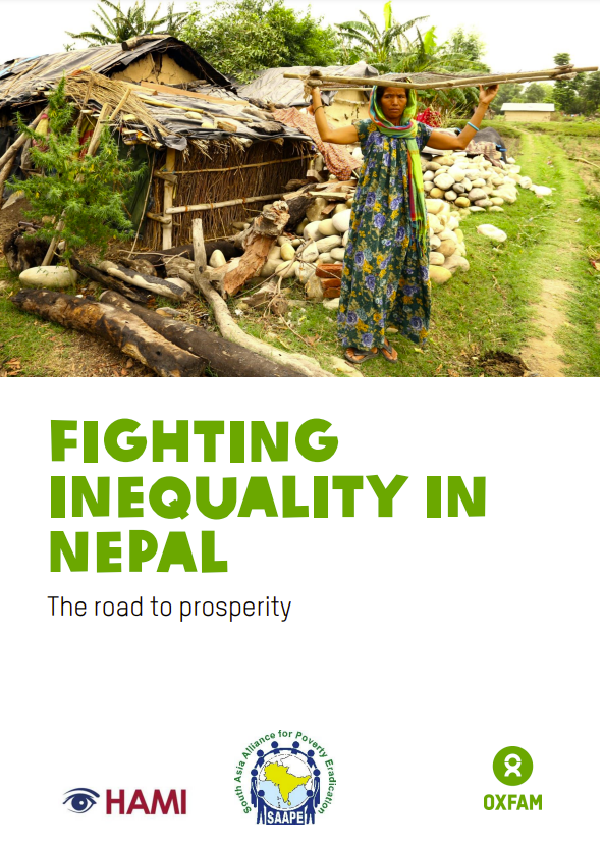

Today, more than 8.1 million Nepalis live in poverty. Women and girls are more likely to be poor, despite the significant contribution they make to the economy, especially through unpaid care and household work. More than one-third of Nepal’s children under five years are stunted, and 10% suffer wasting due to acute malnutrition.4 Without a concerted effort to tackle inequality and pursue policies that benefit the many rather than the richest few, the poorest and most marginalized Nepalis will continue to be excluded from progress.

This report seeks to take stock of the context and drivers of inequality in Nepal, and offer evidence-based recommendations that can support the government’s commitment to tackling inequality. To build a more equal country that leaves nobody behind, Nepal must act now to put the right policies in place and enable citizens and social movements to advocate for progressive change and hold decision-makers to account.

THE GAP BETWEEN RICH AND POOR IN NEPAL

Trends in income and wealth tell a clear story about the gap between the rich and poor in Nepal: economic inequality is extreme and growing.

In 2010/11, Nepal had one of the highest income Gini coefficients in the world, at 49.42, and the level of income disparity had increased considerably in the preceding fifteen years. The Palma ratio, which compares the income share of the top 10 % and the bottom 40 %, shows a similar trend. Today, the income of the richest 10% of Nepalis is more than three times that of the poorest 40%.

In fact, in the five years leading up to 2010/11, only the richest fifth of Nepal’s population saw their income share increase. The income share decreased for everyone else. This is hardly surprising when we consider the scale of the wage divide between top earners and the rest. In Nepal, top bank executives earn more than 100 times the salary of an average worker.

There are also significant geographical divides in income. Between 1995/96 and 2010/11 the average income in urban areas was consistently more than double that of rural areas, and the Mountain and Tarai regions have lower average per capita incomes than Hills region. These low-income areas have higher poverty levels, less infrastructure and services, and are home to more ethnic minorities. They are places where economic and horizontal inequalities combine to hold poor and marginalized groups further back.

Inequality of wealth is also substantial in Nepal, and the wealth Gini is significantly higher than the income Gini at 0.74 (per capita), underlining how money is trickling upwards over time. The richest 10% of Nepal’s population have more than 26 times the wealth of the poorest 40%.

The scale of wealth inequality becomes even more extreme when we look at the very richest individuals. The richest person in Nepal saw his net worth rise by $200m in 2018. This represented a 14.5% rise from 2017, taking his total net worth to $1.5bn. The rise in this person’s wealth could pay for more than half of Nepal’s spending on social protection. It would also take a poor Nepali more than 100,000 years to earn this amount.

Land inequality is the oldest and most fundamental type of wealth inequality. More than 66% of the population depend on land for their livelihood in Nepal, yet land is concentrated in the hands of a rich minority. The wealthiest 7% of households own around 31% of agricultural land. More than half of Nepali farmers own less than 0.5 hectares of land, and 29% of the population do not own any land at all. Women work long hours on agricultural land, yet 81% are landless. Minorities are also less likely to own land, with landlessness as high as 44% among Dalits in the Tarai region. Despite repeated election promises, Nepal is still waiting for muchneeded land reform which will redistribute the country’s most significant asset.

Economic inequality in turn affects life chances. A poor child in Nepal is nearly three times more likely to die before they are five years old than a rich child. Half of the poorest women in Nepal have no education at all, compared with one in a hundred of the richest men.