Child marriage is a marriage or similar union, formal or informal, between a child under a certain age – typically age 18 – and an adult or another child. The vast majority of child marriages are between a girl and a man and are rooted in gender inequality.

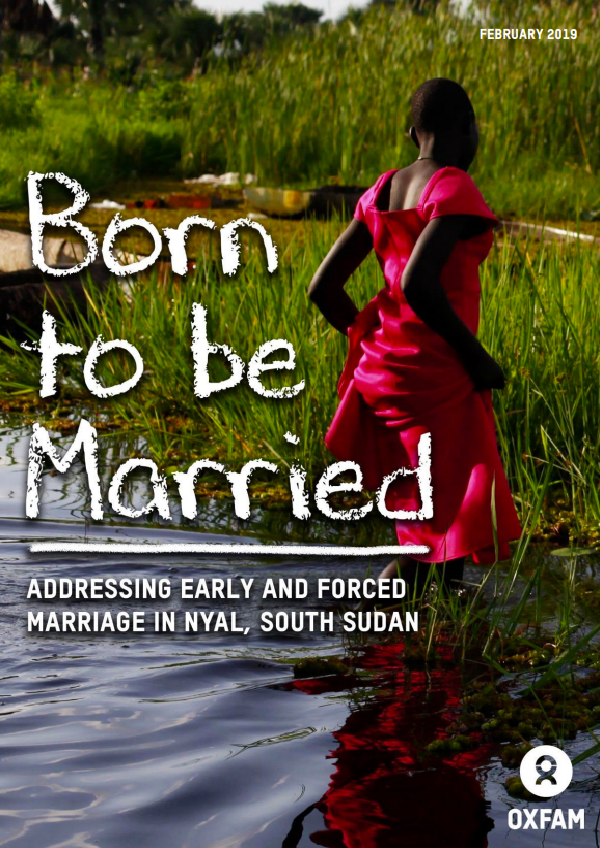

Recent research by Oxfam has found that the rate of child, early, and forced marriage (CEFM) in Nyal – an area that has bordered some of the most brutal fightings in South Sudan’s five-year conflict – are among some of the highest rates in the world. In Nyal, located in Panyijiar County of former Unity State, an estimated 71% of girls are married before the age of 18, a significantly higher rate than the national pre-conflict average of 45%. The research also revealed that 10% of girls and women in Nyal are married before the age of 15.

It is not possible to draw concrete conclusions as to why rates of CEFM in Nyal seem higher than the national rate before the conflict began – especially as the underpinning cultural, social, and economic drivers found in Nyal generally follow national patterns. However, the findings from this report suggest that the practice may also be more pervasive in other areas than national pre-conflict trends would suggest.

High rates of CEFM in South Sudan take place in a context in which women and girls face threats to their rights and well-being throughout their lives. The UN and ceasefire monitors have noted that there is growing evidence that rape has been used as a weapon of war, and that women and girls have been routinely abducted and forced into sexual slavery. Additionally, humanitarian organizations have highlighted that domestic and other forms of gender-based violence have also increased since the start of the conflict.

Since South Sudan’s leaders signed a peace deal in September 2018, there has been a marked reduction in fighting in the country. Yet, rates of sexual violence continue to be extremely high. Meanwhile, while leaders have agreed to ensure that 35% of executive positions are held by women, it is not encouraging that they have so far been unable to achieve this quota in all but one of the bodies set up to date to oversee the transitional period.

Any vision of a recovering South Sudan must be one that protects women and girls from violence, nurtures their rights, and empowers them to lead. Ending CEFM is one vital step in that direction.

The devastating impacts of child, early and forced marriage

Child, early and forced marriage has many devastating consequences: it increases girls’ risk of death or complications during pregnancy and childbirth in a country with one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the world; it is one of the primary reasons why 76% of South Sudanese girls are out-of school; and, it puts girls at greater risk of sexual, physical and emotional violence.

In Nyal, community members were very aware of these risks. Women, men, adolescent girls, and boys all highlighted the impacts of the practice on maternal health, and CEFM was identified as the most common reason girls in Nyal drop out of school. Yet, all adolescent girls interviewed expressed a strong desire to continue with their education. Indeed, in one focus group, adolescent girls said they motivated themselves to perform well in school to mitigate the risk of early marriage since it could motivate their parents or relatives to support their further education. Community members also highlighted the profound impacts CEFM had on the mental health of women and girls, even leaving some to contemplate suicide.

Community members also spoke of how domestic violence, including marital rape is very common and generally seen as normal. In a survey conducted with nearly 200 women and adolescent girls in Nyal, 88% of married women and girls said that they had experienced or witnessed physical violence between husband and wife, while 84% said they experienced or witnessed sexual violence between husband and wife.

Poverty and hunger are pushing women and girls into marriage

No pre-conflict baseline exists for Nyal, and CEFM has long been common in South Sudan. However, in focus group discussions and interviews, community members described how the extended impacts of the conflict have interacted with the practice.

While Oxfam’s research was not able to determine if the rates of CEFM are increasing in Nyal as a result of the conflict, anecdotal evidence from other sources suggests this may indeed be the trend in South Sudan. In Nyal, community members spoke of how the dynamics and driving forces behind the practice have changed since the conflict started in 2013. Conflict-fuelled poverty and food insecurity are now considered to be the most common reasons for families to marry off their young daughters. Additionally, girls displaced by conflict were considered at greater risk of being married before 18. The increased threats of sexual violence and breakdown of rule of law – including respect for traditional authority and customs – were also linked to CEFM in Nyal. While the signing of a peace deal in September provides some hope that the situation in South Sudan may improve, the conditions that have exacerbated girls’ risk of CEFM remain. Recovery will be gradual and will require sustained peace and substantial investment.