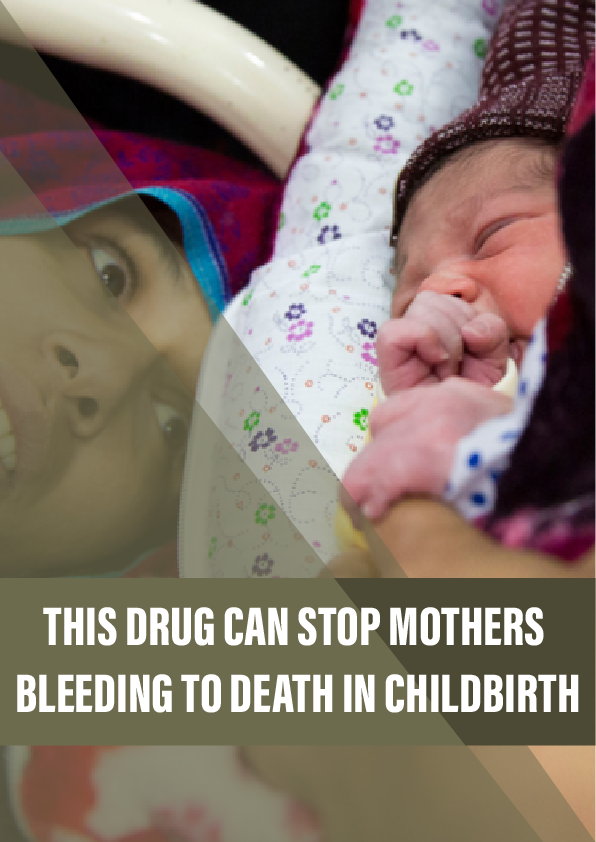

We now know there’s a cheap, safe treatment that could save thousands of lives each year. But those who need it can’t always access it.

Twenty-eight weeks into her first pregnancy, Rabia’s worst fears were realised. She went into labour, and the baby was stillborn. The bleeding started the next day.

“It was severe bleeding, uncontrolled,” Rabia recalls. “The doctors and nurses were changing the bed sheets after every two or three minutes. They were red with blood.”

She was at a hospital in her hometown of Taxila, north of the Pakistani capital Islamabad. The hospital was small and poorly equipped; it employed hardly any gynaecologists, and did not have the facilities to give Rabia a blood transfusion or to surgically explore the cause of the haemorrhage. As her condition worsened and the bleeding continued unabated, panicked medical staff referred her to a larger hospital, over an hour’s drive away, in the nearby city of Rawalpindi.

By the time she reached the next hospital, everything was a blur. She had lost so much blood that she was experiencing multiple organ failure: her kidneys, liver and lungs were all beginning to fail. In Pakistan, blood banks are generally in short supply, and on top of this Rabia has a rare blood type. In a race against the clock, doctors tested the blood of the relatives who had travelled with her.

Her husband desperately called friends, colleagues, anyone he could think of who could quickly get to the hospital. Those that matched gave blood, which was transfused into Rabia immediately. At the same time, doctors sought to stop the bleeding and warned her family that she might not survive. But, after ten days in hospital, she made a full recovery.

As she struggled to make sense of her experience, Rabia – who five years later is now 31 and studying for a PhD in environmental sciences – looked up every medical paper she could find about the horror she had experienced. As she read, she realised that she was one of the lucky ones. Postpartum haemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal death worldwide, responsible for around 100,000 deaths every year.

The condition is usually defined as blood loss of more than 500 ml within 24 hours of a vaginal birth, or more than 1,000 ml, together with signs of decreased blood circulation, following a caesarean.

Reference:

- The WOMAN trial website.

- The paper on the CRASH-2 trial, published in 2013.

- The findings of the WOMAN trial, published in 2017.