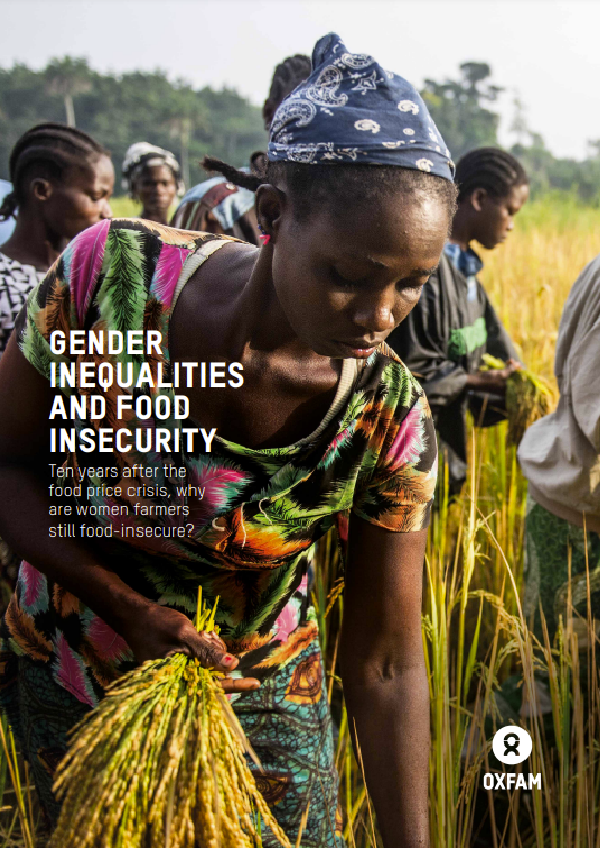

Gender inequalities and food insecurity

Ten years after the food price crisis, why are women farmers still food insecure?

World food prices increased dramatically in 2007 and the first and second quarters of 2008, creating a global crisis and causing political and economic instability and social unrest in both poor and developed nations. The food price crisis of 2007–08 had devastating impacts on the world’s poorest people, especially for smallholder farmers and in particular for women, who face discrimination and a heavy burden of household responsibility.

The global response to the crisis saw the launch of numerous new initiatives and instruments, but funding has been insufficient and policies have failed to address the structural deficiencies in the global food system.

Ten years on, in light of climate change and increased conflict, new policies are needed to rebalance the system to meet the needs of smallholder communities, with a renewed focus on meeting the needs and aspirations of women.

The 2007-08 food price crisis and a second price spike in 2010-11 had devastating impacts on the world’s poorest people, deepening their poverty and seriously undermining their right to food. Smallholder farmers and women (60% of the world’s chronically hungry people in 2009), were disproportionately affected. The global response launched numerous new initiatives and instruments, but funding has been insufficient and policies have failed to address the global food system’s structural deficiencies, instead offering ‘business as usual.’

Ten years later, we are drifting away from the international commitment to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 (zero hunger). The global food-insecure population has risen since 2014, reaching 821 million in 2017, with rural women amongst the worst affected. Twenty African countries relied on external food aid in 2009; the number hit 31 in 2019. Key drivers of hunger, including violent conflict, climate change and economic instability, contribute to destitution and even famine-like conditions, as in Yemen.

Rice export bans and large-scale purchases by major importers such as the Philippines pushed prices further upwards. Like diversion of maize to biofuels, this created distrust of global markets. But there was great variation in ‘price transmission’ from global to domestic markets. Generally, importdependent countries had higher transmission rates, but many national policies dampened such effects.

Women and girls pay the price The threat of soaring prices was particularly challenging for those whose rural livelihoods were already precarious. These affected food producers as well as consumers, as the overwhelming majority of small-scale farmers are net food buyers. The prohibitive cost of inputs (fertilizers, fuel, etc.) offset any opportunities higher output prices might have created.

Because agricultural gender inequalities remain strong, women farmers are particularly at risk of hunger, especially when crisis strikes. On average, rural women account for nearly half the agricultural workforce in developing countries. Despite their crucial roles in household food security, they face discrimination and limited bargaining power. Patriarchal norms create disadvantages for women farmers, specifically in land rights (small plots, difficulties attaining ownership, discriminatory inheritance rights), productive resources (no access to credit, extension services or inputs), unpaid work, insecure employment and exclusion from decision making and political representation. Within the household, because of weaker bargaining position they frequently eat least, last and least well. Women farmers who control resources generally have better-quality diets.