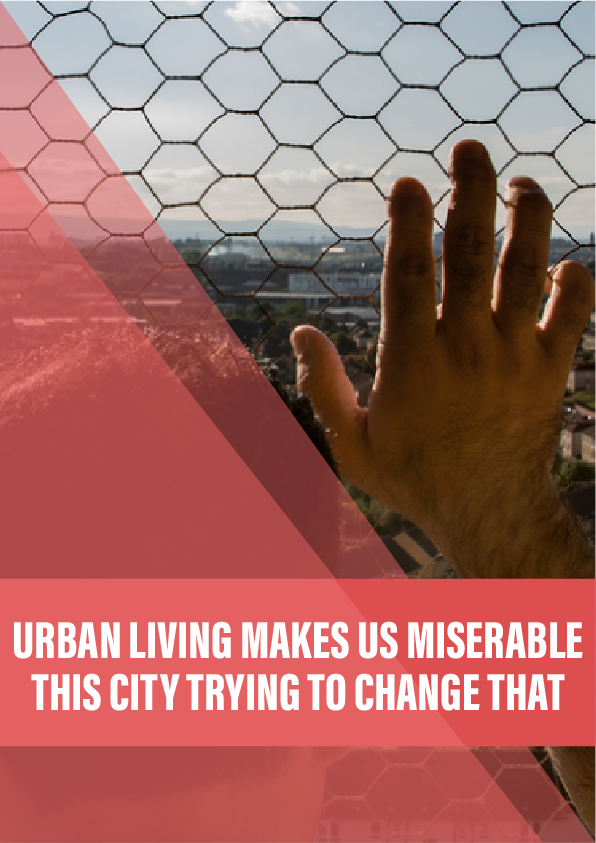

If you live in Glasgow, you are more likely to die young. Men there die a full seven years earlier than their counterparts in other UK cities. Until recently, the causes of this excess mortality remained a mystery.

“Deep-fried Mars bars,” some have speculated. “The weather,” others suggested. For years, those reasons were as good as any. In 2012, the Economist described it thus: “It is as if a malign vapour rises from the Clyde at night and settles in the lungs of sleeping Glaswegians.”

The phenomenon has become known as the Glasgow Effect. But David Walsh, a public health programme manager at the Glasgow Centre for Population Health, who led a study on the excess deaths in 2010, wasn’t satisfied with how the term was being used. “It turned into a Scooby-Doo mystery but it’s not an exciting thing. It’s about people dying young, it’s about grief.”

He wanted to work out why Glaswegians have a 30 per cent higher risk of dying prematurely – that is, before the age of 65 – than those living in similar post-industrial British cities. In 2016 his team published a report looking at 40 hypotheses – from vitamin D deficiency to obesity and sectarianism. “The most important reason is high levels of poverty, full stop,” says Walsh. “There’s one in three children who are classed as living in poverty at the moment.”

But even with deprivation accounted for, mortality rates in Glasgow remained inexplicable. Deaths in each income group are about 15 per cent higher than in Manchester or Liverpool. In particular, deaths from “diseases of despair” – drug overdoses, suicides and alcohol-related deaths – are high. In the mid-2000s, after adjusting for sex, age and deprivation, there was almost a 70 per cent higher mortality rate for suicide in Glasgow than in the two English cities.

Reference: