alking by the side of her house, Rimiko Yoshinaga points at the broad, vine-encrusted tree her grandfather used to climb. During one of the most famous environmental disasters in history, this tree stood over the calm, clear waters of the Shiranui Sea. He would perch up there and call down to say whether the fish were coming, Rimiko says.

The view today is jarringly different. Now the steep edge of Myojin Point in Minamata, Japan, doesn’t overlook the water. Standing there now, you see roads, athletics fields, three separate museum facilities, a seaside memorial park and a scenic bamboo garden – because bamboo roots grow sideways instead of down. Under all this new land is a plastic seal. And under that are millions of tonnes of mercury sludge.

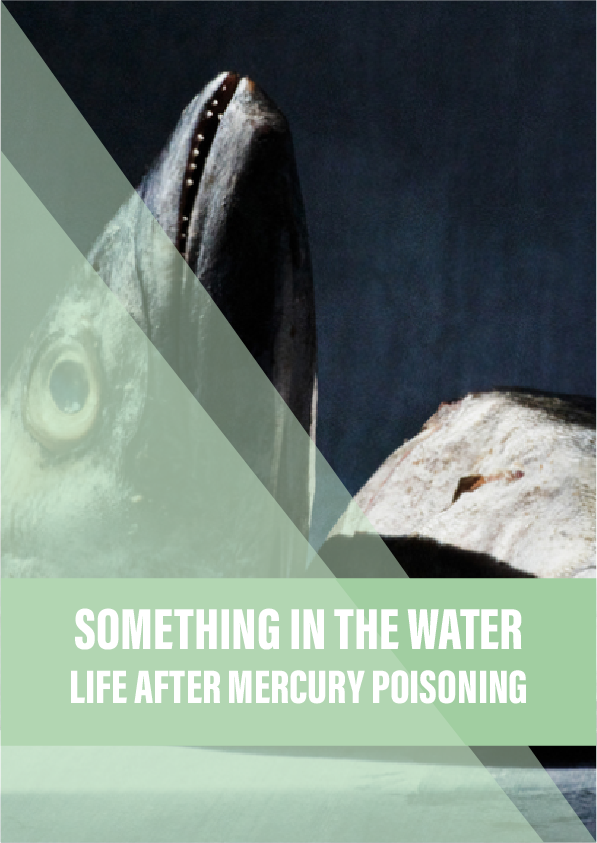

Reclaimed after a long, expensive construction project, this was ground zero for a mystery illness known first as ‘strange disease’ or ‘sauntering disease’ or, ominously, ‘dancing cat disease’. Now it’s just called Minamata disease. The cause? From 1932 to 1968, the Chisso chemical factory discharged up to 600 tonnes of mercury into what was then a harbour. The factory was using the mercury to speed along a reaction that produced acetaldehyde, an ingredient in many plastics. But the company lost so much mercury in the process that it later established a subsidiary to mine it back from polluted sediment nearby.

After flowing out of the factory’s drainage channel, some of the mercury was taken in by plankton, which were then eaten by bigger things like horse mackerel, sardines and shellfish, which in turn were eaten by still bigger creatures like cutlass fish and black porgy. At every step, the mercury – a potent neurotoxin – became more and more concentrated, until it ended up between a pair of chopsticks.

In her living room, Rimiko brings out green tea and local pastries, sits down with her mother and husband, and starts talking. Like almost everyone else in Minamata, and especially like the three other families living in their small hamlet close to the pollution’s source, they ate a lot of seafood in the early 1950s. They didn’t know. Rimiko’s grandfather was a fisherman – every day he brought some of his catch home. Her father had a job at the factory that caused the pollution, but he himself would go fishing after coming home at night. Her elder brother gathered shellfish and crabs.

Reference: