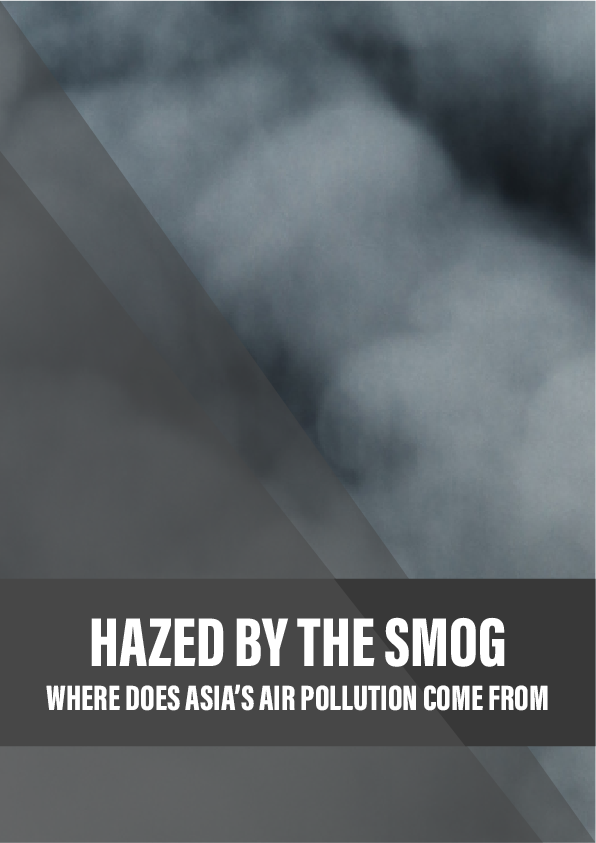

A haze has periodically wafted over Asia for 20 years. But despite rising public health concern, the pollution remains as opaque as the smoke itself, Mike Ives reports.

At the age of 13, Tan Yi Han could not see the edge of his schoolyard. It was 1998 in Singapore, the wealthy city-state known for its tidy streets and clean, green image. But for much of that particular school year, clouds of smoke shrouded the skyline. The record-setting air pollution, which had begun in 1997 and lasted for months, caused a 30 per cent spike in hospital visits. It would later be remembered as one of South-east Asia’s worst-ever “haze episodes”.

Haze episodes have occurred in South-east Asia nearly every year since. Back in 1998, and for years afterwards, Tan didn’t think too deeply about them. Yet at some point in his late 20s, he began to wonder: where did the haze come from? And why did it keep coming back?

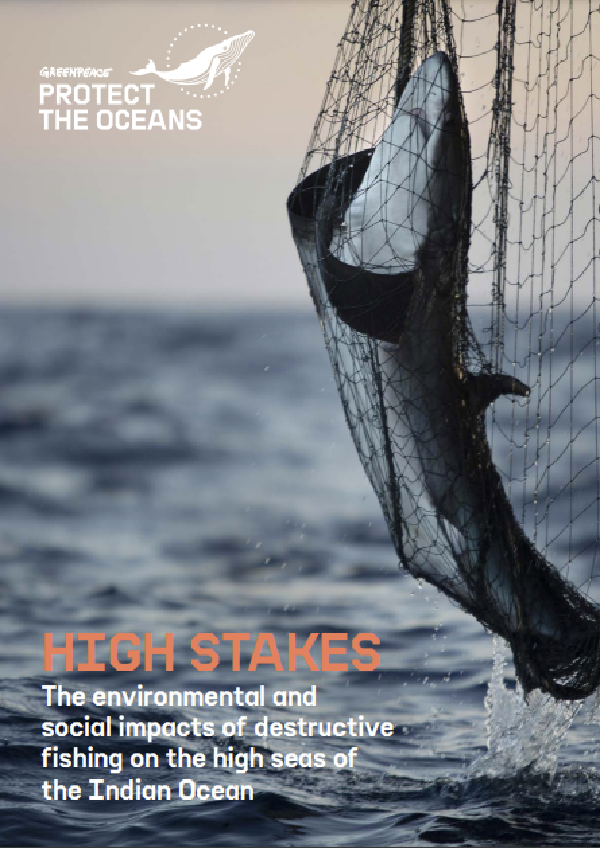

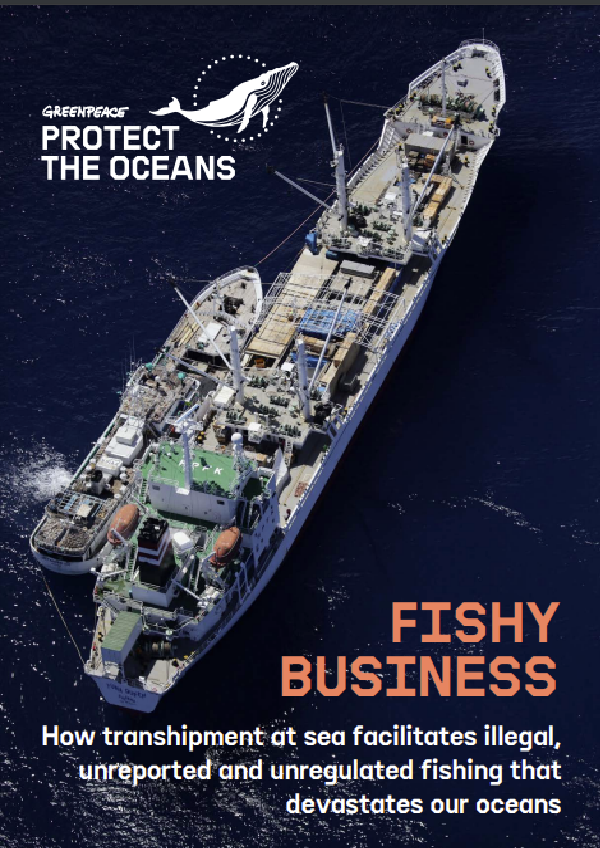

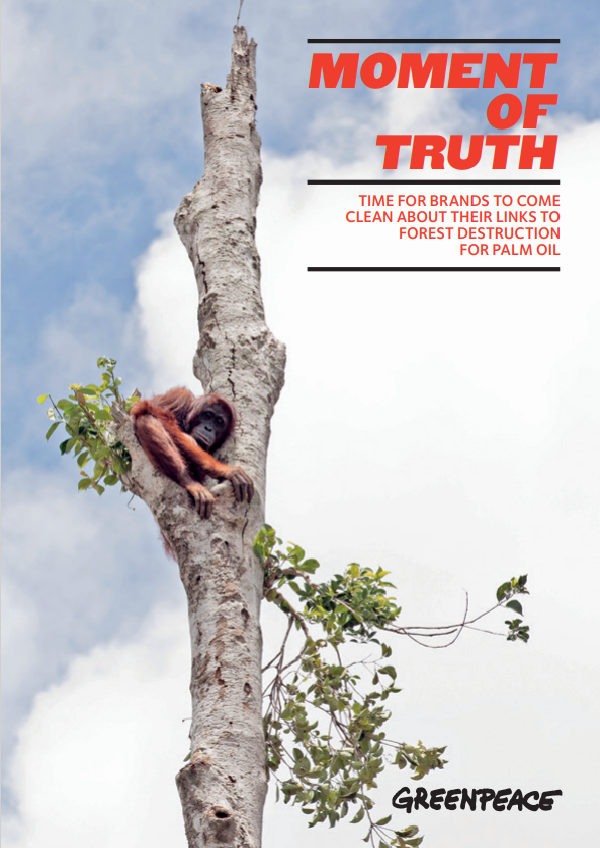

Air pollution kills around 7 million people every year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), accounting for one in eight deaths worldwide in 2012. The main causes of death were stroke and heart disease, followed by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer, and respiratory infections among children.

It is especially bad in the Asia-Pacific region, which has a population of over 4.2 billion and high population density. China and India alone, with a combined population of around 2.7 billion, are both enormous sources and victims of air pollution.

In 2010, 40 per cent of the world’s premature deaths caused by air pollution were in China, the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide, according to a survey published in the Lancet. The University of Hong Kong’s School of Public Health reported more than 3,000 premature deaths in the city in 2013, and the situation in many mainland Chinese cities is reckoned to be far worse. A poll by the US Pew Research Center found that 47 per cent of Chinese citizens thought air pollution to be a “very big” problem in 2013 (up from 31 per cent in 2008). It is now a central focus for many Chinese environmental groups and a growing source of anxiety for the country’s leadership.

Reference:

- A research paper estimating global mortality attributable to smoke from landscape fires. Published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives in 2012.

- ‘Wildfire Research Confirms Health Hazards of Peat Fire Smoke’ – a 2011 article from the US Environmental Protection Agency.

- The UN Environment Programme’s page on urban air pollution.

- The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil.

- The Singapore government’s haze update page.