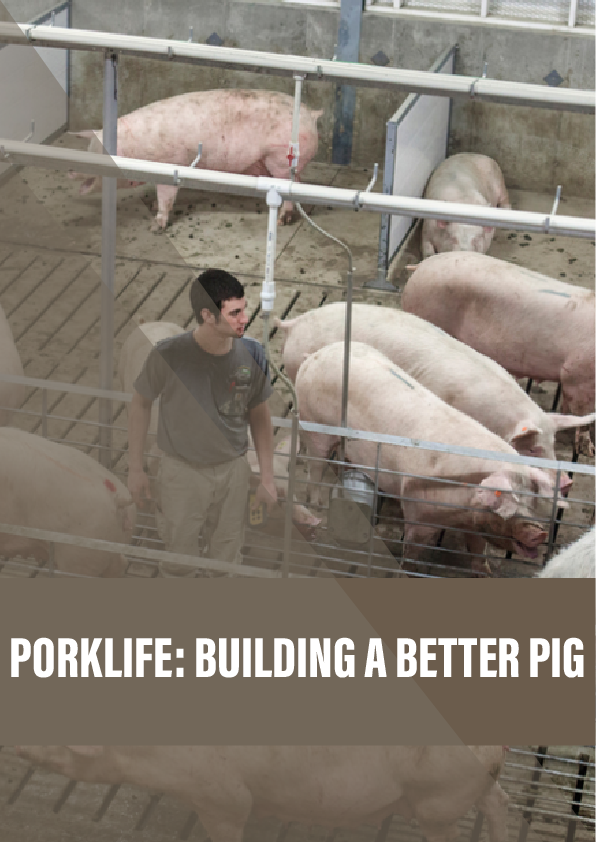

How have the farm animals of today been shaped by centuries of domestication and selective breeding? Sujata Gupta investigates.

Passing fields of soy, corn and towering bleach-white windmills fanning out across windy plains, I arrive early one morning somewhere between Chicago and Indianapolis at a place that promises “sow much fun”.

The Pig Adventure, housing 3,000 sows and producing 80,000 piglets per year, sits alongside a 36,000-cow Dairy Adventure, with murmurings of further adventures for fish and chickens. This is “agro-Disneyland”, a place where rides have been replaced by adorable pink piglets and 72-cow robotic milking parlours (or cow “merry-go-rounds” as our guide calls them).

I line up next to a retired couple and an extended family with three freckled kids from Chicago, and our tour starts inside a sleek lobby outfitted with touch-screens and billboards illuminating the intelligence of pigs – as smart as three-year-olds, better at learning tricks than dogs, outranked in brainpower only by chimps, dolphins and elephants. We pass through a mock shower where animated bubbles slide down the walls to clean us (a feeling akin to being ensconced inside a car during a carwash) and into a wide, carpeted corridor. Everything smells as pleasantly antiseptic as a dentist’s office. Arriving at a viewing area, we ogle some real pigs through thick, soundproof panes of glass.

Here, visitors can see for themselves how, even in today’s global, supermarket era, ‘Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations’ – or factory farms, as they’re better known – can continue to operate on gargantuan scales while still paying heed to animal welfare. Places like The Pig Adventure exist because this clash of practical and moral needs is becoming a massive consumer sticking point.

The fact is, with a global population projected to reach 9 billion by 2050, meat-eating is skyrocketing – meat production has tripled over the last four decades. We need to produce a lot of meat, considerably more than we do today, to meet demand – but we also want to reduce animal suffering. Conscientious carnivores may harbour romantic visions of returning to an earlier, more wholesome way of life, where animals live outdoors surrounded by rolling hills and lush woodlands. But such ideals are expensive and impossible to scale up, leaving today’s farmers asking how, or even if, we can both mass-produce animals and treat them right.

Reference:

- Sam White’s essay ‘From globalized pig breeds to capitalist pigs: A study in animal cultures and evolutionary history’ (2011).

- Bernard Rollin’s essay ‘This Ain’t Agriculture’, published in the Routledge Handbook of Human-Animal Studies (2014).

- Ruth Harrison’s book Animal Machines (1964).

- Bill Muir’s paper on the selection of chickens, ‘Group selection for adaptation to multiple-hen cages: selection program and direct responses’ (1996).

- Wageningen University article on efforts to breed social animals.