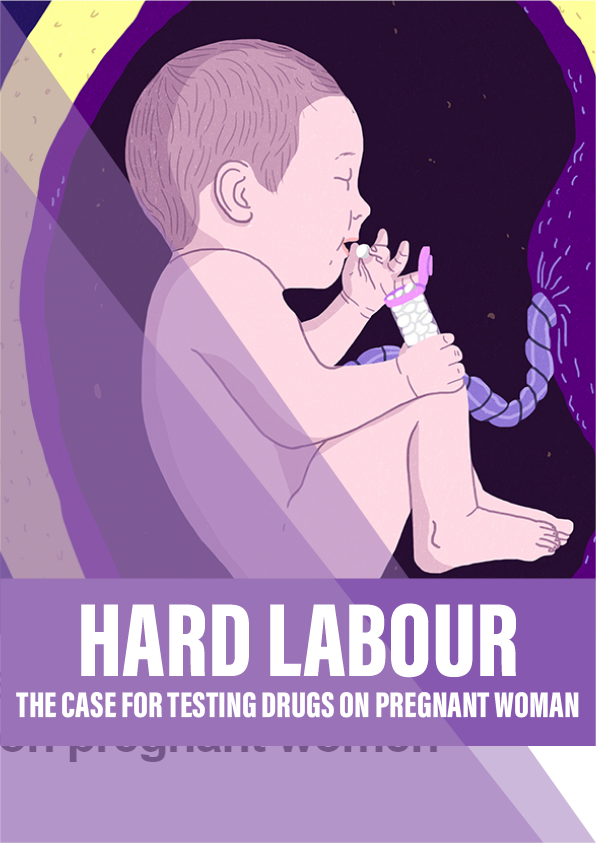

Traditionally, expectant mothers have been excluded from clinical trials, but could this practice be doing more harm than good? Emily Anthes investigates.

When the heart stops beating, minutes matter. With every minute that passes before a rhythm is restored, a patient’s odds of survival plummet. Which is why Anne Lyerly was surprised when, one night 20 years ago, she got a phone call from a doctor who had paused in the middle of treating a patient in cardiac arrest. Lyerly was a newly minted obstetrician; the caller was an internal medicine resident who was desperately trying to resuscitate a dying patient. A pregnant dying patient. He had called because his supervisor wanted to know whether a critical cardiac drug would be safe for the woman’s fetus.

Lyerly was stunned. Most medications are never tested in pregnant women and, although she knew that there was a chance the compound might harm the fetus, her response was unequivocal. “You need to tell him he needs to save her life,” she told the resident. “It doesn’t matter what drug he’s using. She’s dying.”

In the years since, Lyerly, now an ob-gyn and bioethicist at the University of North Carolina, has found herself fielding such questions again and again, from colleagues, patients and friends eager to know whether it is safe for a pregnant woman to stay on her antidepressants, take her migraine medication or use her asthma inhaler.

Sometimes the answer is obvious: a dying woman should get a drug that would save her life, regardless of the risk it might pose to the fetus. But often Lyerly didn’t have such definitive answers. Because it has long been considered unethical to include expectant mothers in clinical trials, scientists simply don’t know whether many common medicines are safe for pregnant women. Of the more than 600 prescription drugs that the US Food and Drug Administration approved between 1980 and 2010, 91 per cent have been so meagrely researched that their safety during pregnancy remains uncertain.

Over the last few years, however, a small, tight-knit group of ethicists, including Lyerly, have become determined to reverse this longstanding scientific neglect of pregnant women. Science and society, they argue, have got it utterly wrong: our efforts to protect women and their fetuses have actually put them both in jeopardy. “Ethics doesn’t preclude including pregnant women in research,” says Lyerly. “Actually, ethics requires it.”

Reference:

- The Second Wave Initiative

- UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS): The main service communicates only with healthcare professionals, but patients can access information leaflets via the associated service bumps.

- MotherToBaby: A service of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS), MotherToBaby provides counselling and advice to women and doctors throughout the USA and Canada. Callers may be routed to an affiliated service in their area.

- European Network of Teratology Information Services (ENTIS): ENTIS provides links to local teratology services throughout Europe.

- MotherSafe: MotherSafe is a telephone information service for women in New South Wales, Australia.