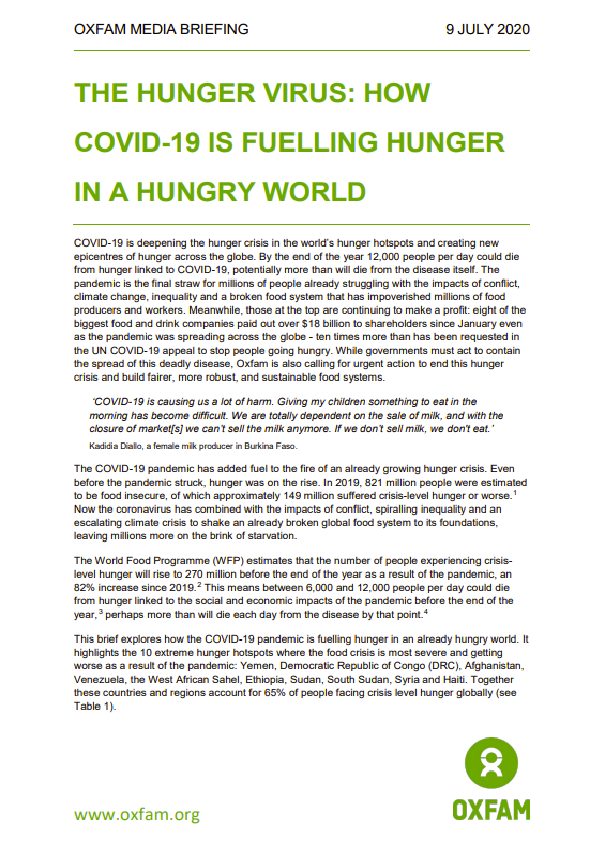

COVID-19 is deepening the hunger crisis in the world’s hunger hotspots and creating new epicentres of hunger across the globe. By the end of the year 12,000 people per day could die from hunger linked to COVID-19, potentially more than will die from the disease itself. The pandemic is the final straw for millions of people already struggling with the impacts of conflict, climate change, inequality and a broken food system that has impoverished millions of food producers and workers. Meanwhile, those at the top are continuing to make a profit: eight of the biggest food and drink companies paid out over $18 billion to shareholders since January even as the pandemic was spreading across the globe – ten times more than has been requested in the UN COVID-19 appeal to stop people going hungry. While governments must act to contain the spread of this deadly disease, Oxfam is also calling for urgent action to end this hunger crisis and build fairer, more robust, and sustainable food systems.

‘COVID-19 is causing us a lot of harm. Giving my children something to eat in the morning has become difficult. We are totally dependent on the sale of milk, and with the closure of market[s] we can’t sell the milk anymore. If we don’t sell milk, we don’t eat.’

Kadidia Diallo, a female milk producer in Burkina Faso.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added fuel to the fire of an already growing hunger crisis. Even before the pandemic struck, hunger was on the rise. In 2019, 821 million people were estimated to be food insecure, of which approximately 149 million suffered crisis-level hunger or worse. 1 Now the coronavirus has combined with the impacts of conflict, spiralling inequality and an escalating climate crisis to shake an already broken global food system to its foundations, leaving millions more on the brink of starvation.

The World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that the number of people experiencing crisislevel hunger will rise to 270 million before the end of the year as a result of the pandemic, an 82% increase since 2019. 2 This means between 6,000 and 12,000 people per day could die from hunger linked to the social and economic impacts of the pandemic before the end of the year, 3 perhaps more than will die each day from the disease by that point.

This brief explores how the COVID-19 pandemic is fuelling hunger in an already hungry world. It highlights the 10 extreme hunger hotspots where the food crisis is most severe and getting worse as a result of the pandemic: Yemen, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Afghanistan, Venezuela, the West African Sahel, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Syria and Haiti. Together these countries and regions account for 65% of people facing crisis level hunger globally.

But the story does not end there. New hunger hotspots are also emerging. Middle-income countries such as India, South Africa, and Brazil are experiencing rapidly rising levels of hunger as millions of people that were just about managing have been tipped over the edge by the pandemic. Even the world’s richest countries are not immune. Data from the UK government shows that during the first few weeks of the lockdown as many as 7.7 million adults reduced their meal portion sizes or missed meals, and up to 3.7 million adults sought charity food or used a food bank. 5

This brief also explores why so many people are going hungry and why so many more are so vulnerable to hunger. It shines a light on a food system that has trapped millions of people in hunger on a planet that produces more than enough food for everyone. 6 A system that has enabled eight of the biggest food and beverage companies in the world to pay out over $18bn to their shareholders since the start of 2020, even as the COVID-19 crisis unfolded across the globe. 7 This is over 10 times the amount of food and agriculture assistance funds requested in the UN’s COVID-19 humanitarian appeal.8

Oxfam recognizes the need for governments to take urgent action to contain the spread of the coronavirus but is also calling on them to act now to end this hunger crisis. To save lives now and in the future, governments must: (1) fully fund the UN’s humanitarian appeal, (2) build fairer, more resilient, and more sustainable food systems, beginning with a high-level Global Food Crisis Summit when the Committee on World Food Security meets in October, (3) promote women’s participation and leadership in decisions on how to fix the broken food system, (4) cancel debt to allow lower-income countries to put social protection measures in place, (5) support the UN’s call for a global ceasefire, and (6) take urgent action to tackle the climate crisis.