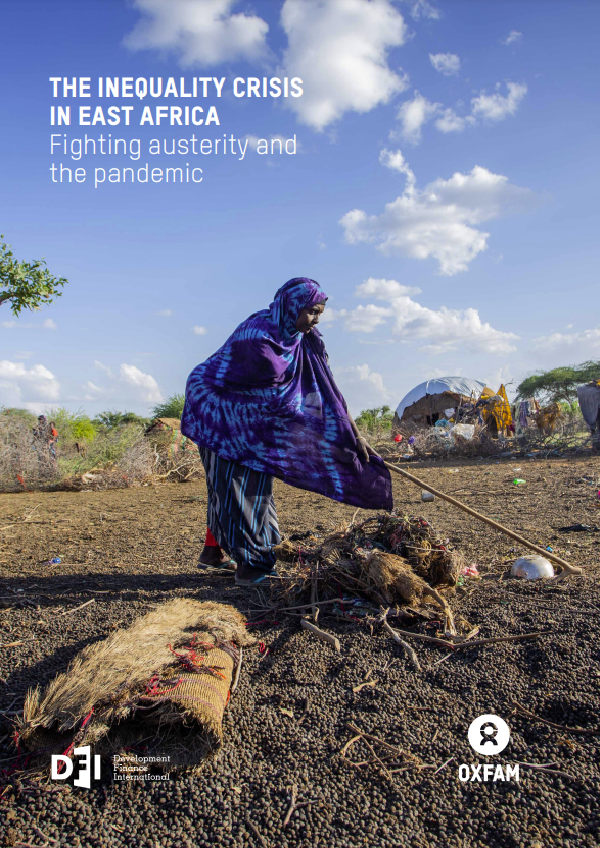

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed millions into poverty in East Africa, and worsened inequality. The economic crisis continues, due to the obscene global vaccine inequality, which means that only 4% of East African citizens had been fully vaccinated against COVID-19, compared with 71% in high-income countries by mid-January2022.

Many East African governments were already hamstrung by high debt and budget deficits before the pandemic, preventing them from responding with large recovery programmes. Other governments did increase spending, but five are now forecasting major budget cuts for 2022–26. These cuts will stop them combating the increases in poverty and inequality that have resulted from COVID-19.

However, building back during and after the pandemic offers East African governments a once-in-a-generation opportunity to do what their citizens want: make their economic systems fairer by increasing taxes on wealthy and large corporations, boost public spending (especially on healthcare, education and social protection), and improving workers’ rights. With external support, including through comprehensive debt relief and more aid, they can reduce inequality drastically and eliminate extreme poverty by 2030.

Summary

In 2018 and again in 2020, Development Finance International and Oxfam warned that East Africa2 had high levels of inequality, and governments in the region showed low commitment to reducing it. In 2021, using the Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index (CRII) framework devised by DFI and Oxfam to focus on East Africa in more detail, this report finds that this continues.

In this report, we analyse COVID-19’s impact on growth, poverty and inequality, as well as the responses of governments, their creditors and the IMF and World Bank. We also assess whether governments were well prepared to deal with a pandemic, based on their commitment to fighting inequality through public services, progressive taxation and workers’ rights, and the role of governance in influencing this commitment.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, East African countries on average were lagging 33% behind North Africa and 30% behind Southern Africa in their commitment to fighting inequality and were doing only a third as well as the best performers globally. They performed relatively well on progressive taxation, but this was not translating into public services that reached people living in poverty. The poorest people also suffered from very weak or non-existent labour rights. Comparative analysis with global governance indices (the Corruptions Perception Index and Open Budget Index) shows high correlations, indicating that corruption and budget transparency have a strong relationship with a commitment to anti-inequality policies.

Most countries in East Africa seemed to be less hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, but the first half of 2021 saw a surge in infection and death rates, forcing some countries to reintroduce containment measures. Health systems which were extremely weak before the pandemic have been stretched to the limits. Protracted school closures have affected millions of learners, especially the poorest who could not switch to online learning. While COVID-19 has since slowly abated, there is still the risk of another resurgence due to global vaccine inequality. By mid-January 2022 a paltry 4% of the region’s population had been fully jabbed.

In addition, it is clear that the pandemic is the region’s worst economic crisis in decades, pushing millions into poverty and exacerbating inequality. The immediate economic impact of the pandemic was huge, with East Africa losing $15.7bn in GDP in 2020 due to lower-than-expected growth, and losing working hours corresponding to 10 million jobs. Households were hit particularly hard, with surveys from four countries showing that more than 60% of citizens reported losing income or work due to COVID-19.

The fiscal support programmes enacted by governments were limited by high levels of debt and budget deficits before COVID-19, and even these programmes will be rolled back in most countries by 2022. In addition, to reduce their budget deficits, five governments in the region are planning to introduce a daunting level of austerity in the next five years: on average, they will cut annual spending massively, by $4.7bn compared with 2021. Oxfam’s review of IMF COVID-19 loans to 85 countries between March 1, 2020, and March 15, 2021, showed that the IMF has encouraged 73 countries to pursue austerity policies during recovery, among them five East African countries. Restoring these cuts would be enough for these governments to quadruple their health expenditures and keep them at that higher level through to 2026. In South Sudan, a country of 13 million people with more military generals than doctors pre-COVID-19, health spending could rise by 13 times.

Spending cuts on this scale will dramatically narrow the fiscal space for social spending essential to attaining the Sustainable Development Goals, exacerbate COVID-19-induced vulnerability, and increase inequality and poverty. This will be especially true for women and girls, already especially hard hit by the pandemic, which has increased the burden on women at the frontline of health and social care, while slashing other earnings in the labour-intensive sectors dominated by women during lockdowns.

Debt servicing is another growing pressure on government budgets. Even before COVID-19, it was reaching astronomical levels in most East African countries, with governments spending on average five times as much on domestic and external debt services as on health. In 2020–21, debt service accounted for 35.2% of government revenue in East Africa, a burden that the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative was woefully inadequate in reducing.

The combination of budget cuts, rising debt and a slow recovery due to global vaccine inequity risks raising the East African inequality crisis to new heights.

However, building back during and after the pandemic offers East African governments a once-in-a-generation opportunity to do what their citizens want: to avoid this austerity and make their economic systems fairer. Raising more revenue through progressive taxation could allow governments to increase the social sector spending needed to reduce inequality and poverty, without increasing the budget deficit. If they increase their tax revenues by just 1% of GDP, they would raise an additional $4.9bn each year on average for the next five years, which is enough to raise health spending by an average 77% each year across the region.

For most of the countries in the region, tax revenue has been chronically low for years. In 2019, average national tax revenue in the region was only 12.8% of GDP, with only Kenya over 16%. In addition, an average of 56% of tax revenue comes from indirect taxes on goods and services, which generally hit people living in poverty harder. Governments can do much more to raise this revenue in progressive ways that help fight inequality, by increasing income tax rates and collection, sealing tax loopholes, strengthening tax authorities, and reinforcing wealth taxes. Taxing the wealthy and corporations would give governments a way out of the crisis, and surveys from three of the nine countries show that more than 71% of citizens think it is fair to tax the rich more in order to fund programmes that benefit people living in poverty.

It is also important that tax revenues are spent transparently on public services that reduce inequality the most. Currently most East African countries are falling far short of the spending targets set at African Union summits based on calculations of needs to reach the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for universal coverage of education, health and social protection, and the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme targets for agriculture spending.

However, there is a limit to what government spending alone can do to reduce the very high levels of inequality produced by the market in many East African countries. These have some of the world’s highest levels of informal or vulnerable employment, which deprives workers of their labour rights. So governments will need to create and enforce legislation to improve labour rights (especially for women) and minimum wages. They will also need to work harder to tackle structural causes of inequality, notably unequal access to assets like land or financial services.

Regional and international organizations could also help steer countries away from the destructive path of austerity towards an inclusive and broad-based recovery. The East African Community could, for example, agree common minimum income tax rates and rules sharply reducing tax incentives in order to encourage faster progress towards regional convergence targets, as the West African Economic and Monetary Union has already done. The African Union could help by monitoring much more closely the social and agricultural spending commitments made at previous AU summits, and by advocating even more loudly for the debt relief and new financing measures needed to accelerate SDG progress. The IMF and World Bank need to encourage countries to increase progressive taxes and combat tax dodging to fund stronger public services. They should also push for improved labour rights and social protection. Urgent and ambitious debt relief is needed to prevent austerity and free up money for social spending. More aid is needed to end unacceptable vaccine inequality.

East Africa is at a crossroads. The pandemic has dramatically increased poverty and inequality in the region, and post-pandemic austerity will make this worse. It is not yet too late to change direction. By increasing taxation on those who can best afford it, and receiving more comprehensive debt relief and urgent external funding, East African countries can spend more on public services and enhance workers’ rights. This will allow them to beat both austerity and the pandemic, and better protect themselves against future pandemics. But it will happen only if governments, regional institutions and the global community drastically increase their commitment to reduce inequality and eliminate poverty by 2030.