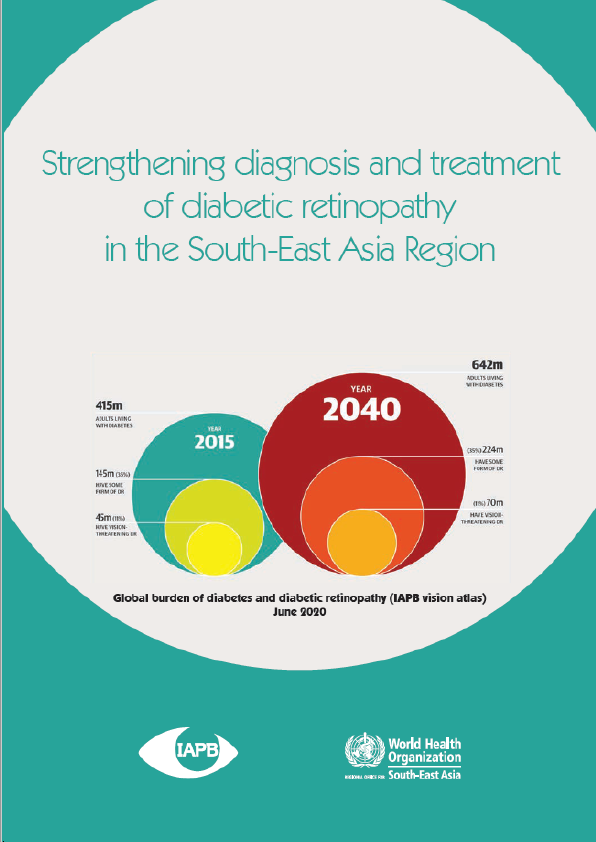

Diabetes is a global epidemic and diabetic retinopathy (dr), the commonest microvascular complication of diabetes, is an emerging cause of visual impairment and blindness. It is estimated that by 2040, 642 million people will have diabetes, 35% (224 million) of them will have someform of diabetic retinopathy, and 11% (70 million) will have sight-threatening retinopathy. The vision loss expert group reported that, despite global efforts, the prevalence of dr increasedby 25% between 1990 and 2015 (crude prevalence 1990: 0.032%; 2015: 0.04%), while theprevalence of other causes of visual impairment have decreased. This disparity is due to a rise in the worlds population, an increase in the numbers of people with diabetes, increased longevity and ageing populations. Paradoxically, there is a higher prevalence of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy in low- and middleincome countries, than in high-income countries. The international diabetes federation (idf) has estimated that in 2019, south-east asia was home to 87.6 million people with diabetes, while 30.6 and 9.6 million people possibly had diabetic retinopathy and sight-threatening retinopathy, respectively. Diabetes mellitus (dm) is also responsible for reduced, quality-adjusted life years and early death. Adding to the problem is the concurrent global rise in the cost of diabetes care, and unequal planned expenditure on diabetes, in low- and middle-income countries. There is a need for a systematic approach. Over the years, many country-specific and global guidelines of evidence-based diabetic retinopathy have been developed. The scopes of these guidelines are nearly similar: screening to detect sight-threatening retinopathy, referral for appropriate care, and treatment using the latest technique and technology.

Many countries in the sea region do not have diabetic retinopathy treatment and operation guidelines, despite being home to the largest population with diabetes. The international agency for the prevention of blindness (iapb) formed a south-east asia diabetic retinopathy expert group and sought help from the who sea regional office in new delhi to convene a three-day meeting in december 2019, to analyse the existing diabetic retinopathy guidelines, and formulate a guideline more

specific to the region.

Retina or public health specialists were pooled from bangladesh, bhutan, india, indonesia, myanmar, maldives, nepal, sri lanka, and thailand. In addition to their deliberations, the guidelines have derived guidance and wisdom from two experts from the who sea regional office: dr thaksaphon thamarangsi, director, healthier populations and noncommunicable

diseases, and dr patanjali dev nayar, regional adviser, disability & injury prevention and rehabilitation. I also place on record the encouragement of dr poonam khetrapal singh, regional director of the who south-east asia region; she has always encouraged all efforts to reduce needless blindness in the region and specifically, the formulation of these guidelines.