In the summer of 2013, Edward Snowden shook the world with a trove of disclosed documents from the National Security Agency (NSA), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and a host of other global three-letter agencies. For more than a year, there were weekly (if not daily) revelations of just how extensive these agencies’ digital information-gathering capabilities were, particularly those of the United States. It felt as though the NSA was able to get any information that went through internet or phone networks that wasn’t encrypted plus some information that was weakly encrypted and some more information that wasn’t encrypted on corporate servers. That feeling is close to the truth.

At the time, I had been engaged in environmental activism and was aware of how social movements had historically suffered from state repression that was made possible through spying. The sheer extent of the information that the NSA and CIA were able to gather meant that suppression efforts by the State could be that much easier and more effective. The more information the State knows about your activities, the easier it is for it to interfere with your goals.

So I was worried. Could we combat climate change when the odds were stacked against all the groups working to do so? What about systemic racism? Did we have any hope?

Not long after the Snowden revelations, I partnered with the Civil Liberties Defense Center (CLDC), a nonprofit that provides legal support to social movements that “seek to dismantle the political and economic structures at the root of social inequality and environmental destruction.” The CLDC gives know-your-(legal)-rights trainings to social movement participants, emphasizing how to protect and invoke one’s First and Fourth Amendment rights: the right to free speech and the right to no illegal searches and seizures. These rights are eroded with mass surveillance. This is quite clear with Fourth Amendment rights, but for First Amendment rights, legal scholars often point to this chilling effect: citizens restrict their speech if they know they are being surveilled. To complement the CLDC’s legal trainings, I started regularly holding digital security trainings for activists centered on the premise that encryption is the only way to protect your First and Fourth Amendment rights in the modern world of mass surveillance. This book has grown out of these educational efforts.

Downloading a “Secure” App Isn’t Enough

It isn’t enough to download a “secure” app. First, what does “secure” even mean? Security is a complex, subjective, and multifaceted concept. While perfect freedom from risk is usually out of reach, especially when digital technologies are involved, strong relative protections are possible. In order to evaluate or at least explain (and convince a group of people to take advantage of) the relative protections of an app requires some understanding about cryptography and what information is at risk (and with what likelihood) when using a given app or digital service.

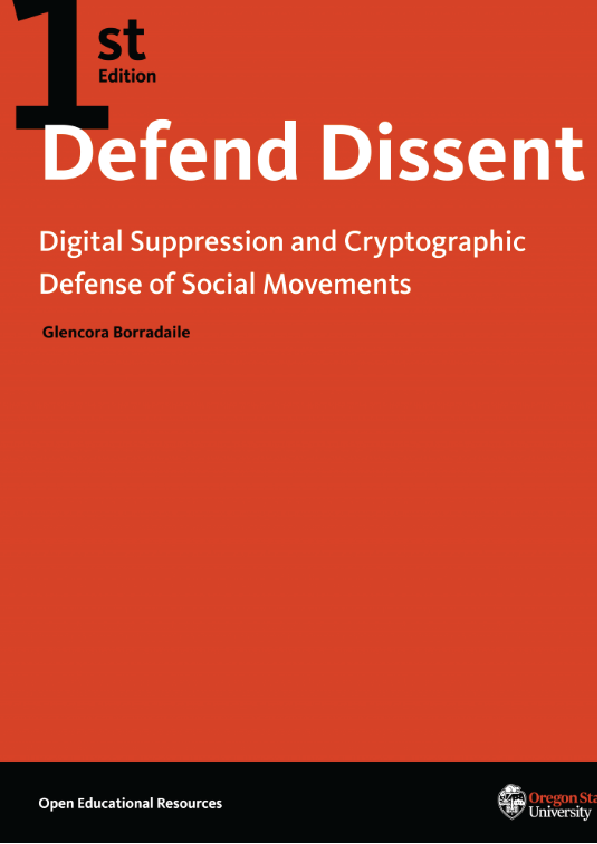

Our trainings scratch the surface of the information that I would like to impart. Social movement participants tend to be busy people and often want a set of simple and doable digital security recommendations from people they trust. My goal with this book (and the companion course at Oregon State University, CS175: Communications Security and Social Movements) is to increase the number of people who know enough to make those recommendations (or at least know how and where to learn more).